5.4: Classical School

- Page ID

- 15944

Leviathan (1651), Hobbes made a few assumptions about human beings.[1] He assumed humans were at conflict with one another, pursued their self-interests, and were rational. Moreover, people would create authority figures out of fear of others, and people should democratically create rules that all citizens must follow. Hobbes wanted a new type of government, one that was ruled by the people and not by monarchs. He believed people had natural rights such as life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. If we grant the assumption that people are rational, we would assume people have the ability to consider the possible consequences of their actions. Hobbes was one of the first social contract thinkers. Social contract thinkers believed people would invest in the laws of their society if, and only if, they know government protected them from those who break the law. People will give up a little of their self-interests as long as everyone reciprocates.

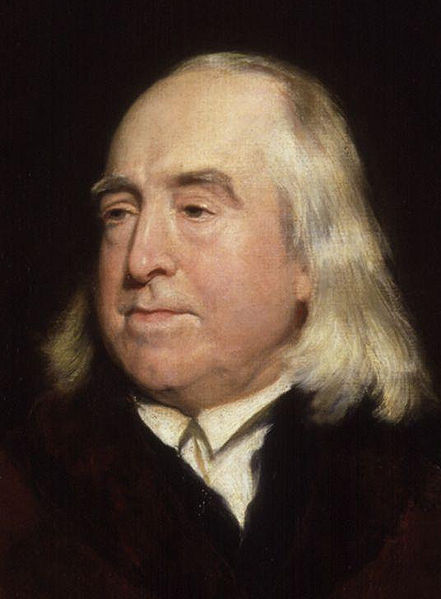

Hedonism is the assumption that people will see maximum pleasure and avoid pain (punishment). Consequently, if we grant the assumptions of classical theory, we can hold people 100% responsible for their actions because it was a choice. These assumptions have been the basis for the American criminal justice system since its inception. Although theories may have changed the landscape of understanding criminal behavior and may have changed the philosophies of punishments over time, the criminal justice system has maintained the assumption that crime is a choice. Hence, we can hold offenders 100% responsible for their actions.

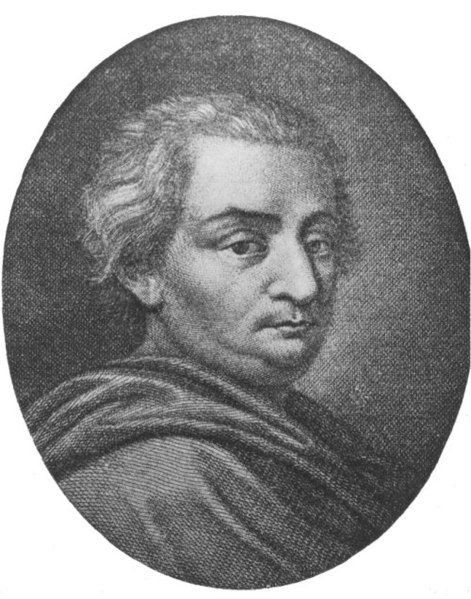

An Essay on Crimes and Punishment (1764), which attacked Europe’s use of harsh treatment.[2] Ideally, he wanted to change the excessive and cruel punishment by applying rationalistic, social contract ideas. At the time, judges had tremendous power to determine guilt and create laws based on their decisions. Intellectuals well received his essay at the time, but the Catholic Church banned it. His ideas were exceptionally radical at the time, mainly because his writing questioned the power structures at the time.

Essay was highly influential during the Enlightenment, and it may have served as a model during the creation of the American Criminal Justice system. For example, Beccaria advocated that punishments should fit the crime and be proportional to the harm done, laws should only be determined by the legislature, judges should only determine guilt, and every person should be treated equally under the law. He claimed the sole purpose of the law was to deter people from committing the crime. Deterrence can be accomplished if the punishment is certain, swift, and severe. These may seem like common sense today, but they were considered radical ideas at the time.

[3]

- Hobbes, T. (1651/1968). Leviathan. Baltimore, MD: Penguin Books. ↵

- Beccaria, C. (1963). On crimes and punishments (H. Paolucci, Trans.). Indianapolis, IN: Bobbs-Merril. (Original work published in 1764) ↵

- Bentham, J. (1823). Introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ↵