6.1: The State of the Prisons

- Page ID

- 16062

Prisoners in the United States and elsewhere have always confronted a unique set of contingencies and pressures to which they were required to react and adapt in order to survive the prison experience. However, over the last several decades beginning in the early 1970s and continuing to the present time a combination of forces has transformed the nation's criminal justice system and modified the nature of imprisonment. The challenges prisoners now face in order to both survive the prison experience and, eventually, reintegrate into the free world upon release have changed and intensified as a result.

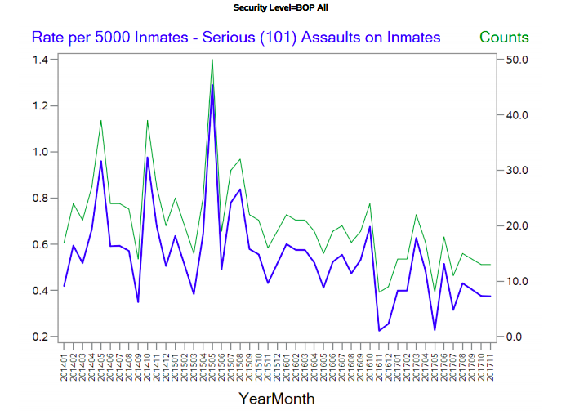

Figure 6.1 Bureau of Prison Statistics March 2018 Report.

Among other things, these changes in the nature of imprisonment have included a series of inter-related, negative trends in American corrections. Perhaps the most dramatic changes have come about as a result of the unprecedented increases in rate of incarceration, the size of the U.S. prison population, and the widespread overcrowding that has occurred as a result. Over the past 25 years, penologists repeatedly have described U.S. prisons as "in crisis" and have characterized each new level of overcrowding as "unprecedented." By the start of the 1990s, the United States incarcerated more persons per capita than any other nation in the modern world, and it has retained that dubious distinction for nearly every year since. The international disparities are most striking when the U.S. incarceration rate is contrasted to those of other nations to whom the United States is often compared, such as Japan, Netherlands, Australia, and the United Kingdom. In the 1990s, as Marc Mauer and the Sentencing Project have effectively documented the U.S. rates have consistently been between four and eight times those for these other nations.

The combination of overcrowding and the rapid expansion of prison systems across the country adversely affected living conditions in many prisons, jeopardized prisoner safety, compromised prison management, and greatly limited prisoner access to meaningful programming. The two largest prison systems in the nation California and Texas provide instructive examples. Over the last 30 years, California's prisoner population increased eightfold (from roughly 20,000 in the early 1970s to its current population of approximately 160,000 prisoners). Yet there has been no remotely comparable increase in funds for prisoner services or inmate programming. In Texas, over just the years between 1992 and 1997, the prisoner population more than doubled as Texas achieved one of the highest incarceration rates in the nation. Nearly 70,000 additional prisoners added to the state's prison rolls in that brief five-year period alone. Not surprisingly, California and Texas were among the states to face major lawsuits in the 1990s over substandard, unconstitutional conditions of confinement. Federal courts in both states found that the prison systems had failed to provide adequate treatment services for those prisoners who suffered the most extreme psychological effects of confinement in deteriorated and overcrowded conditions.

Paralleling these dramatic increases in incarceration rates and the numbers of persons imprisoned in the United States was an equally dramatic change in the rationale for prison itself. The nation moved abruptly in the mid-1970s from a society that justified putting people in prison on the basis of the belief that incarceration would somehow facilitate productive re-entry into the free world to one that used imprisonment merely to inflict pain on wrongdoers ("just deserts"), disable criminal offenders ("incapacitation"), or to keep them far away from the rest of society ("containment"). The abandonment of the once-avowed goal of rehabilitation certainly decreased the perceived need and availability of meaningful programming for prisoners as well as social and mental health services available to them both inside and outside the prison. Indeed, it generally reduced concern on the part of prison administrations for the overall well-being of prisoners.

The abandonment of rehabilitation also resulted in an erosion of modestly protective norms against cruelty toward prisoners. Many corrections officials soon became far less inclined to address prison disturbances, tensions between prisoner groups and factions, and disciplinary infractions in general through ameliorative techniques aimed at the root causes of conflict and designed to de-escalate it. The rapid influx of new prisoners, serious shortages in staffing and other resources, and the embrace of an openly punitive approach to corrections led to the "de-skilling" of many correctional staff members who often resorted to extreme forms of prison discipline (such as punitive isolation or "supermax" confinement) that had especially destructive effects on prisoners and repressed conflict rather than resolving it. Increased tensions and higher levels of fear and danger resulted.

The emphasis on the punitive and stigmatizing aspects of incarceration, which has resulted in the further literal and psychological isolation of prison from the surrounding community, compromised prison visitation programs and the already scarce resources that had been used to maintain ties between prisoners and their families and the outside world.

Support services to facilitate the transition from prison to the free world environments to which prisoners were returned were undermined at precisely the moment they needed to be enhanced. Increased sentence length and a greatly expanded scope of incarceration resulted in prisoners experiencing the psychological strains of imprisonment for longer periods of time, many persons being caught in the web of incarceration who ordinarily would not have been (e.g., drug offenders), and the social costs of incarceration becoming increasingly concentrated in minority communities (because of differential enforcement and sentencing policies).

Thus, in the first decade of the 21st century, more people have been subjected to the pains of imprisonment, for longer periods of time, under conditions that threaten greater psychological distress and potential long-term dysfunction, and they will be returned to communities that have already been disadvantaged by a lack of social services and resources.