2.3: A Very Simple Circuit

- Page ID

- 1245

Parts and Materials

- 6-volt battery

- 6-volt incandescent lamp

- Jumper wires

- Breadboard

- Terminal strip

From this experiment on, a multimeter is assumed to be necessary and will not be included in the required list of parts and materials. In all subsequent illustrations, a digital multimeter will be shown instead of an analog meter unless there is some particular reason to use an analog meter. You are encouraged to use both types of meters to gain familiarity with the operation of each in these experiments.

Cross-references

Lessons In Electric Circuits, Volume 1, chapter 1: “Basic Concepts of Electricity”

Learning Objectives

- Essential configuration needed to make a circuit

- Normal voltage drops in an operating circuit

- Importance of continuity to a circuit

- Working definitions of “open” and “short” circuits

- Breadboard usage

- Terminal strip usage

Schematic Diagram

Illustration

Creating a Simple Circuit

This is the simplest complete circuit in this collection of experiments: a battery and an incandescent lamp. Connect the lamp to the battery as shown in the illustration, and the lamp should light, assuming the battery and lamp are both in good condition and they are matched to one another in terms of voltage.

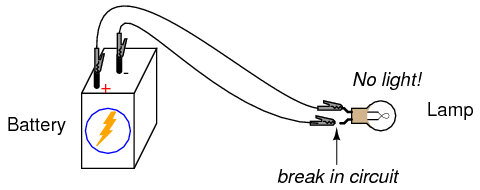

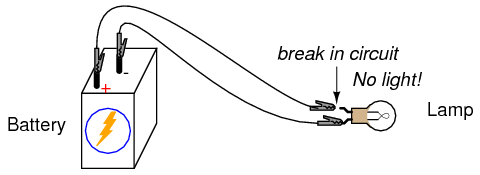

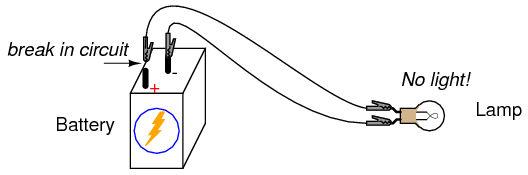

If there is a “break” (discontinuity) anywhere in the circuit, the lamp will fail to light. It does not matter where such a break occurs! Many students assume that because electrons leave the negative (-) side of the battery and continue through the circuit to the positive (+) side, that the wire connecting the negative terminal of the battery to the lamp is more important to circuit operation than the other wire providing a return path for electrons back to the battery. This is not true!

Using your multimeter set to the appropriate “DC volt” range, measure voltage across the battery, across the lamp, and across each jumper wire. Familiarize yourself with the normal voltages in a functioning circuit.

Now, “break” the circuit at one point and re-measure voltage between the same sets of points, additionally measuring voltage across the break like this:

What voltages measure the same as before? What voltages are different since introducing the break? How much voltage is manifested, or dropped across the break? What is the polarity of the voltage drop across the break, as indicated by the meter?

Re-connect the jumper wire to the lamp, and break the circuit in another place. Measure all voltage “drops” again, familiarizing yourself with the voltages of an “open” circuit.

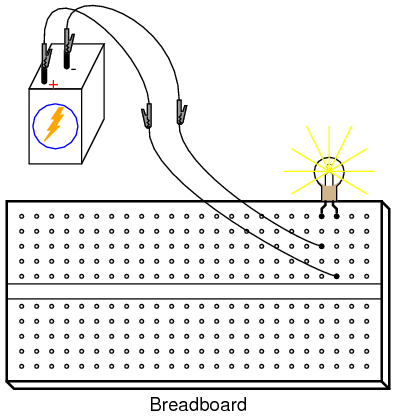

Construct the same circuit on a breadboard, taking care to place the lamp and wires into the breadboard in such a way that continuity will be maintained. The example shown here is only that: an example, not the only way to build a circuit on a breadboard:

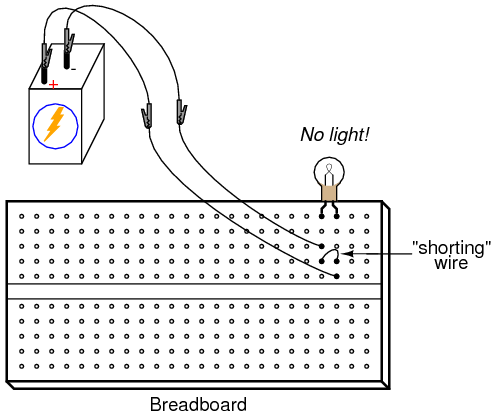

Experiment with different configurations on the breadboard, plugging the lamp into different holes. If you encounter a situation where the lamp refuses to light up and the connecting wires are getting warm, you probably have a situation known as a short circuit, where a lower-resistance path than the lamp bypasses current around the lamp, preventing enough voltage from being dropped across the lamp to light it up. Here is an example of a short circuit made on a breadboard:

An Example of an Accidental Short Circuit

Here is an example of an accidental short circuit of the type typically made by students unfamiliar with breadboard usage:

Here there is no “shorting” wire present on the breadboard, yet there is a short circuit, and the lamp refuses to light. Based on your understanding of breadboard hole connections, can you determine where the “short” is in this circuit?

Tips to Avoid Short Circuits

Short circuits are generally to be avoided, as they result in very high rates of electron flow, causing wires to heat up and battery power sources to deplete. If the power source is substantial enough, a short circuit may cause heat of explosive proportions to manifest, causing equipment damage and hazard to nearby personnel. This is what happens when a tree limb “shorts” across wires on a power line: the limb—being composed of wet wood—acts as a low-resistance path to electric current, resulting in heat and sparks.

You may also build the battery/lamp circuit on a terminal strip: a length of insulating material with metal bars and screws to attach wires and component terminals to. Here is an example of how this circuit might be constructed on a terminal strip: