1.5: Resistance

- Page ID

- 680

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)The Electron Flow through Filament of the Lamp

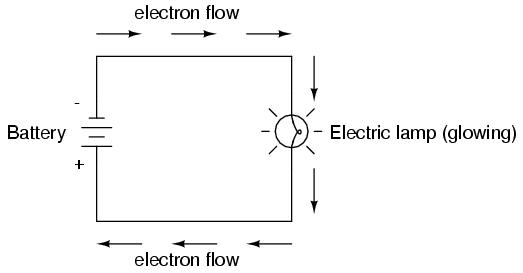

One practical and popular use of electric current is for the operation of electric lighting. The simplest form of electric lamp is a tiny metal “filament” inside of a clear glass bulb, which glows white-hot (“incandesces”) with heat energy when sufficient electric current passes through it. Like the battery, it has two conductive connection points, one for electrons to enter and the other for electrons to exit.

Connected to a source of voltage, an electric lamp circuit looks something like this:

As the electrons work their way through the thin metal filament of the lamp, they encounter more opposition to motion than they typically would in a thick piece of wire. This opposition to electric current depends on the type of material, its cross-sectional area, and its temperature. It is technically known as resistance. (It can be said that conductors have low resistance and insulators have very high resistance.) This resistance serves to limit the amount of current through the circuit with a given amount of voltage supplied by the battery, as compared with the “short circuit” where we had nothing but a wire joining one end of the voltage source (battery) to the other.

When electrons move against the opposition of resistance, “friction” is generated. Just like mechanical friction, the friction produced by electrons flowing against a resistance manifests itself in the form of heat. The concentrated resistance of a lamp’s filament results in a relatively large amount of heat energy dissipated at that filament. This heat energy is enough to cause the filament to glow white-hot, producing light, whereas the wires connecting the lamp to the battery (which have much lower resistance) hardly even get warm while conducting the same amount of current.

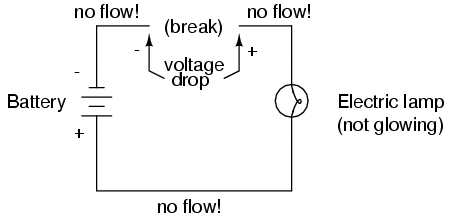

As in the case of the short circuit, if the continuity of the circuit is broken at any point, electron flow stops throughout the entire circuit. With a lamp in place, this means that it will stop glowing:

As before, with no flow of electrons, the entire potential (voltage) of the battery is available across the break, waiting for the opportunity of a connection to bridge across that break and permit electron flow again. This condition is known as an open circuit, where a break in the continuity of the circuit prevents current throughout. All it takes is a single break in continuity to “open” a circuit. Once any breaks have been connected once again and the continuity of the circuit re-established, it is known as a closed circuit.

The Basis for Switching Lamps

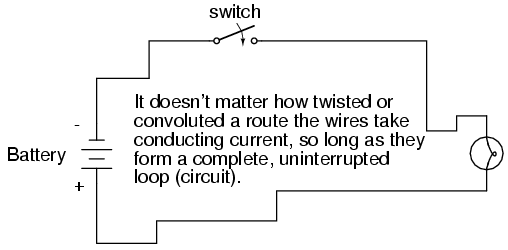

What we see here is the basis for switching lamps on and off by remote switches. Because any break in a circuit’s continuity results in current stopping throughout the entire circuit, we can use a device designed to intentionally break that continuity (called a switch), mounted at any convenient location that we can run wires to, to control the flow of electrons in the circuit:

This is how a switch mounted on the wall of a house can control a lamp that is mounted down a long hallway, or even in another room, far away from the switch. The switch itself is constructed of a pair of conductive contacts (usually made of some kind of metal) forced together by a mechanical lever actuator or pushbutton. When the contacts touch each other, electrons are able to flow from one to the other and the circuit’s continuity is established; when the contacts are separated, electron flow from one to the other is prevented by the insulation of the air between, and the circuit’s continuity is broken.

The Knife Switch

Perhaps the best kind of switch to show for illustration of the basic principle is the “knife” switch:

A knife switch is nothing more than a conductive lever, free to pivot on a hinge, coming into physical contact with one or more stationary contact points which are also conductive. The switch shown in the above illustration is constructed on a porcelain base (an excellent insulating material), using copper (an excellent conductor) for the “blade” and contact points. The handle is plastic to insulate the operator’s hand from the conductive blade of the switch when opening or closing it.

Here is another type of knife switch, with two stationary contacts instead of one:

The particular knife switch shown here has one “blade” but two stationary contacts, meaning that it can make or break more than one circuit. For now this is not terribly important to be aware of, just the basic concept of what a switch is and how it works.

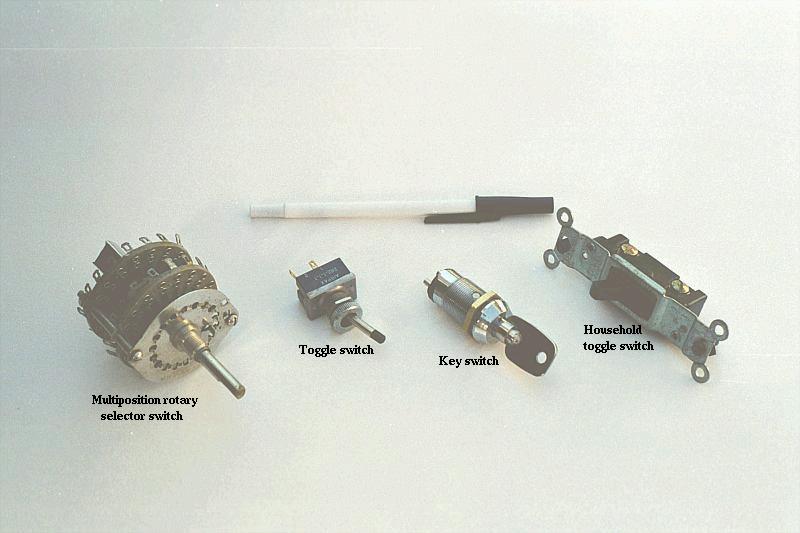

Knife switches are great for illustrating the basic principle of how a switch works, but they present distinct safety problems when used in high-power electric circuits. The exposed conductors in a knife switch make accidental contact with the circuit a distinct possibility, and any sparking that may occur between the moving blade and the stationary contact is free to ignite any nearby flammable materials. Most modern switch designs have their moving conductors and contact points sealed inside an insulating case in order to mitigate these hazards. A photograph of a few modern switch types show how the switching mechanisms are much more concealed than with the knife design:

Opened and Closed Circuits

In keeping with the “open” and “closed” terminology of circuits, a switch that is making contact from one connection terminal to the other (example: a knife switch with the blade fully touching the stationary contact point) provides continuity for electrons to flow through, and is called a closed switch. Conversely, a switch that is breaking continuity (example: a knife switch with the blade not touching the stationary contact point) won’t allow electrons to pass through and is called an open switch. This terminology is often confusing to the new student of electronics, because the words “open” and “closed” are commonly understood in the context of a door, where “open” is equated with free passage and “closed” with blockage. With electrical switches, these terms have opposite meaning: “open” means no flow while “closed” means free passage of electrons.

Review

- Resistance is the measure of opposition to electric current.

- A short circuit is an electric circuit offering little or no resistance to the flow of electrons. Short circuits are dangerous with high voltage power sources because the high currents encountered can cause large amounts of heat energy to be released.

- An open circuit is one where the continuity has been broken by an interruption in the path for electrons to flow.

- A closed circuit is one that is complete, with good continuity throughout.

- A device designed to open or close a circuit under controlled conditions is called a switch.

- The terms “open” and “closed” refer to switches as well as entire circuits. An open switch is one without continuity: electrons cannot flow through it. A closed switch is one that provides a direct (low resistance) path for electrons to flow through.