2.9: Computer Simulation of Electric Circuits

- Page ID

- 692

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)These same programs can be fantastic aids to the beginning student of electronics, allowing the exploration of ideas quickly and easily with no assembly of real circuits required. Of course, there is no substitute for actually building and testing real circuits, but computer simulations certainly assist in the learning process by allowing the student to experiment with changes and see the effects they have on circuits. Throughout this book, I’ll be incorporating computer printouts from circuit simulation frequently in order to illustrate important concepts. By observing the results of a computer simulation, a student can gain an intuitive grasp of circuit behavior without the intimidation of abstract mathematical analysis.

To simulate circuits on computer, I make use of a particular program called SPICE, which works by describing a circuit to the computer by means of a listing of text. In essence, this listing is a kind of computer program in itself, and must adhere to the syntactical rules of the SPICE language. The computer is then used to process, or “run,” the SPICE program, which interprets the text listing describing the circuit and outputs the results of its detailed mathematical analysis, also in text form. Many details of using SPICE are described in volume 5 (“Reference”) of this book series for those wanting more information. Here, I’ll just introduce the basic concepts and then apply SPICE to the analysis of these simple circuits we’ve been reading about.

First, we need to have SPICE installed on our computer. As a free program, it is commonly available on the internet for download, and in formats appropriate for many different operating systems. In this book, I use one of the earlier versions of SPICE: version 2G6, for its simplicity of use.

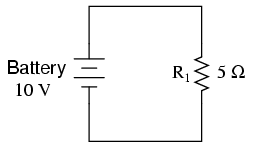

Next, we need a circuit for SPICE to analyze. Let’s try one of the circuits illustrated earlier in the chapter. Here is its schematic diagram:

This simple circuit consists of a battery and a resistor connected directly together. We know the voltage of the battery (10 volts) and the resistance of the resistor (5 Ω), but nothing else about the circuit. If we describe this circuit to SPICE, it should be able to tell us (at the very least), how much current we have in the circuit by using Ohm’s Law (I=E/R).

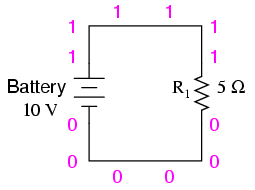

SPICE cannot directly understand a schematic diagram or any other form of graphical description. SPICE is a text-based computer program, and demands that a circuit be described in terms of its constituent components and connection points. Each unique connection point in a circuit is described for SPICE by a “node” number. Points that are electrically common to each other in the circuit to be simulated are designated as such by sharing the same number. It might be helpful to think of these numbers as “wire” numbers rather than “node” numbers, following the definition given in the previous section. This is how the computer knows what’s connected to what: by the sharing of common wire, or node, numbers. In our example circuit, we only have two “nodes,” the top wire and the bottom wire. SPICE demands there be a node 0 somewhere in the circuit, so we’ll label our wires 0 and 1:

In the above illustration, I’ve shown multiple “1” and “0” labels around each respective wire to emphasize the concept of common points sharing common node numbers, but still this is a graphic image, not a text description. SPICE needs to have the component values and node numbers given to it in text form before any analysis may proceed.

Creating a text file in a computer involves the use of a program called a text editor. Similar to a word processor, a text editor allows you to type text and record what you’ve typed in the form of a file stored on the computer’s hard disk. Text editors lack the formatting ability of word processors (no italic, bold, or underlined characters), and this is a good thing, since programs such as SPICE wouldn’t know what to do with this extra information. If we want to create a plain-text file, with absolutely nothing recorded except the keyboard characters we select, a text editor is the tool to use.

If using a Microsoft operating system such as DOS or Windows, a couple of text editors are readily available with the system. In DOS, there is the old Edit text editing program, which may be invoked by typing edit at the command prompt. In Windows (3.x/95/98/NT/Me/2k/XP), the Notepad text editor is your stock choice. Many other text editing programs are available, and some are even free. I happen to use a free text editor called Vim, and run it under both Windows 95 and Linux operating systems. It matters little which editor you use, so don’t worry if the screenshots in this section don’t look like yours; the important information here is what you type, not which editor you happen to use.

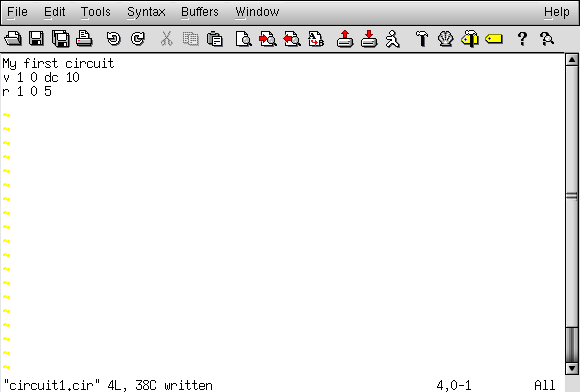

To describe this simple, two-component circuit to SPICE, I will begin by invoking my text editor program and typing in a “title” line for the circuit:

We can describe the battery to the computer by typing in a line of text starting with the letter “v” (for “Voltage source”), identifying which wire each terminal of the battery connects to (the node numbers), and the battery’s voltage, like this:

This line of text tells SPICE that we have a voltage source connected between nodes 1 and 0, direct current (DC), 10 volts. That’s all the computer needs to know regarding the battery. Now we turn to the resistor: SPICE requires that resistors be described with a letter “r,” the numbers of the two nodes (connection points), and the resistance in ohms. Since this is a computer simulation, there is no need to specify a power rating for the resistor. That’s one nice thing about “virtual” components: they can’t be harmed by excessive voltages or currents!

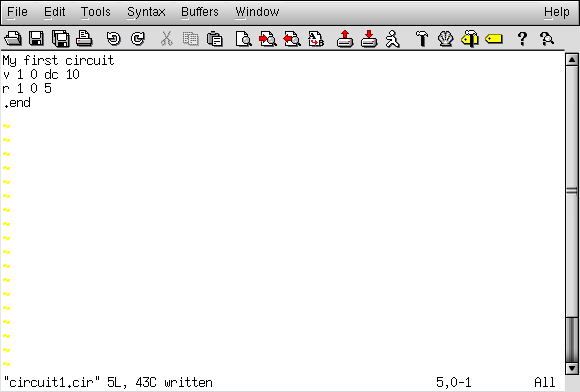

Now, SPICE will know there is a resistor connected between nodes 1 and 0 with a value of 5 Ω. This very brief line of text tells the computer we have a resistor (”r”) connected between the same two nodes as the battery (1 and 0), with a resistance value of 5 Ω.

If we add an .end statement to this collection of SPICE commands to indicate the end of the circuit description, we will have all the information SPICE needs, collected in one file and ready for processing. This circuit description, comprised of lines of text in a computer file, is technically known as a netlist, or deck:

Once we have finished typing all the necessary SPICE commands, we need to “save” them to a file on the computer’s hard disk so that SPICE has something to reference to when invoked. Since this is my first SPICE netlist, I’ll save it under the filename “circuit1.cir” (the actual name being arbitrary). You may elect to name your first SPICE netlist something completely different, just as long as you don’t violate any filename rules for your operating system, such as using no more than 8+3 characters (eight characters in the name, and three characters in the extension: 12345678.123) in DOS.

To invoke SPICE (tell it to process the contents of the circuit1.cir netlist file), we have to exit from the text editor and access a command prompt (the “DOS prompt” for Microsoft users) where we can enter text commands for the computer’s operating system to obey. This “primitive” way of invoking a program may seem archaic to computer users accustomed to a “point-and-click” graphical environment, but it is a very powerful and flexible way of doing things. Remember, what you’re doing here by using SPICE is a simple form of computer programming, and the more comfortable you become in giving the computer text-form commands to follow—as opposed to simply clicking on icon images using a mouse—the more mastery you will have over your computer.

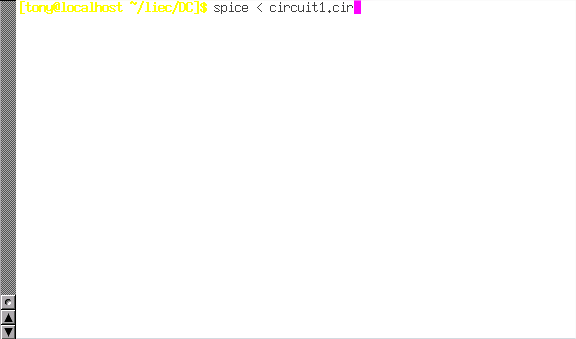

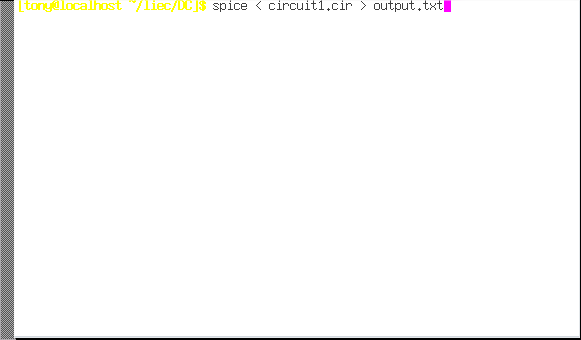

Once at a command prompt, type in this command, followed by an [Enter] keystroke (this example uses the filename circuit1.cir; if you have chosen a different filename for your netlist file, substitute it):

Here is how this looks on my computer (running the Linux operating system), just before I press the [Enter] key:

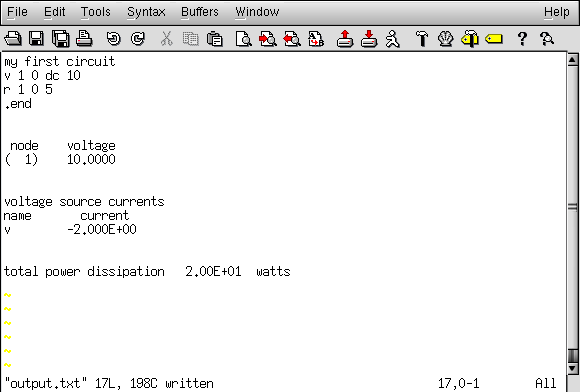

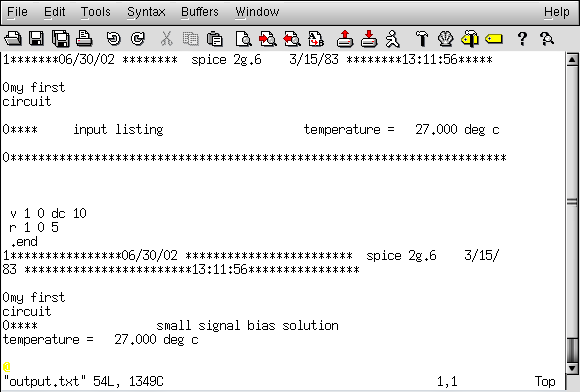

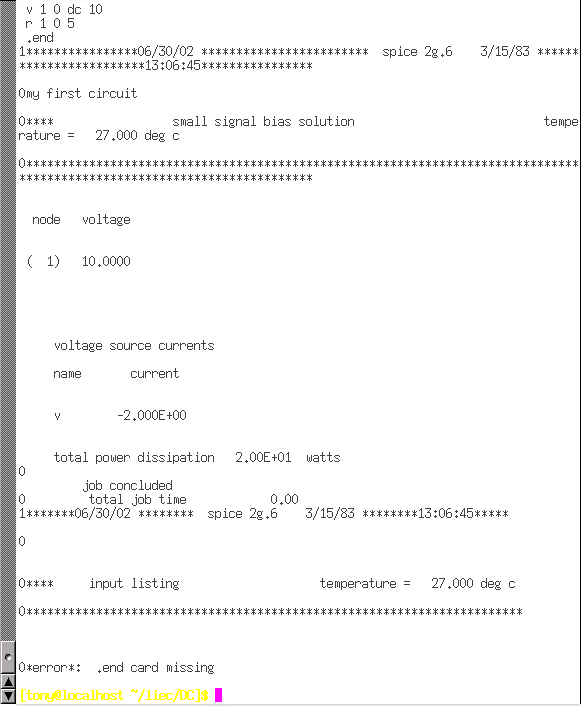

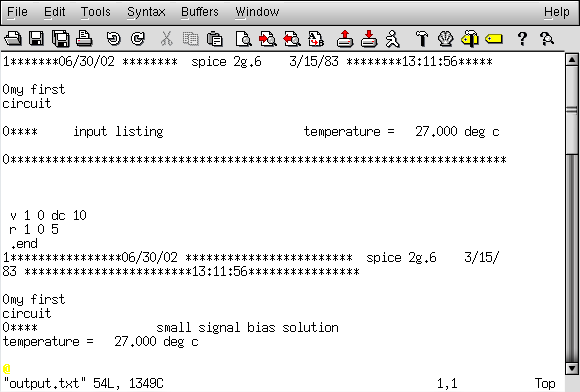

As soon as you press the [Enter] key to issue this command, text from SPICE’s output should scroll by on the computer screen. Here is a screenshot showing what SPICE outputs on my computer (I’ve lengthened the “terminal” window to show you the full text. With a normal-size terminal, the text easily exceeds one page length):

SPICE begins with a reiteration of the netlist, complete with title line and .end statement. About halfway through the simulation it displays the voltage at all nodes with reference to node 0. In this example, we only have one node other than node 0, so it displays the voltage there: 10.0000 volts. Then it displays the current through each voltage source. Since we only have one voltage source in the entire circuit, it only displays the current through that one. In this case, the source current is 2 amps. Due to a quirk in the way SPICE analyzes current, the value of 2 amps is output as a negative (-) 2 amps.

The last line of text in the computer’s analysis report is “total power dissipation,” which in this case is given as “2.00E+01” watts: 2.00 x 101, or 20 watts. SPICE outputs most figures in scientific notation rather than normal (fixed-point) notation. While this may seem to be more confusing at first, it is actually less confusing when very large or very small numbers are involved. The details of scientific notation will be covered in the next chapter of this book.

One of the benefits of using a “primitive” text-based program such as SPICE is that the text files dealt with are extremely small compared to other file formats, especially graphical formats used in other circuit simulation software. Also, the fact that SPICE’s output is plain text means you can direct SPICE’s output to another text file where it may be further manipulated. To do this, we re-issue a command to the computer’s operating system to invoke SPICE, this time redirecting the output to a file I’ll call “output.txt”:

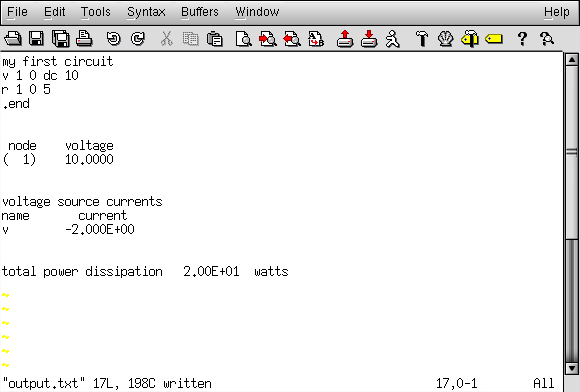

SPICE will run “silently” this time, without the stream of text output to the computer screen as before. A new file, output1.txt, will be created, which you may open and change using a text editor or word processor. For this illustration, I’ll use the same text editor (Vim) to open this file:

Now, I may freely edit this file, deleting any extraneous text (such as the “banners” showing date and time), leaving only the text that I feel to be pertinent to my circuit’s analysis:

Once suitably edited and re-saved under the same filename (output.txt in this example), the text may be pasted into any kind of document, “plain text” being a universal file format for almost all computer systems. I can even include it directly in the text of this book—rather than as a “screenshot” graphic image—like this:

Incidentally, this is the preferred format for text output from SPICE simulations in this book series: as real text, not as graphic screenshot images.

To alter a component value in the simulation, we need to open up the netlist file (circuit1.cir) and make the required modifications in the text description of the circuit, then save those changes to the same filename, and re-invoke SPICE at the command prompt. This process of editing and processing a text file is one familiar to every computer programmer. One of the reasons I like to teach SPICE is that it prepares the learner to think and work like a computer programmer, which is good because computer programming is a significant area of advanced electronics work.

Earlier we explored the consequences of changing one of the three variables in an electric circuit (voltage, current, or resistance) using Ohm’s Law to mathematically predict what would happen. Now let’s try the same thing using SPICE to do the math for us.

If we were to triple the voltage in our last example circuit from 10 to 30 volts and keep the circuit resistance unchanged, we would expect the current to triple as well. Let’s try this, re-naming our netlist file so as to not over-write the first file. This way, we will have both versions of the circuit simulation stored on the hard drive of our computer for future use. The following text listing is the output of SPICE for this modified netlist, formatted as plain text rather than as a graphic image of my computer screen:

Just as we expected, the current tripled with the voltage increase. Current used to be 2 amps, but now it has increased to 6 amps (-6.000 x 100). Note also how the total power dissipation in the circuit has increased. It was 20 watts before, but now is 180 watts (1.8 x 102). Recalling that power is related to the square of the voltage (Joule’s Law: P=E2/R), this makes sense. If we triple the circuit voltage, the power should increase by a factor of nine (32 = 9). Nine times 20 is indeed 180, so SPICE’s output does indeed correlate with what we know about power in electric circuits.

If we want to see how this simple circuit would respond over a wide range of battery voltages, we can invoke some of the more advanced options within SPICE. Here, I’ll use the “.dc” analysis option to vary the battery voltage from 0 to 100 volts in 5 volt increments, printing out the circuit voltage and current at every step. The lines in the SPICE netlist beginning with a star symbol (”*”) are comments. That is, they don’t tell the computer to do anything relating to circuit analysis, but merely serve as notes for any human being reading the netlist text.

The .print command in this SPICE netlist instructs SPICE to print columns of numbers corresponding to each step in the analysis:

If I re-edit the netlist file, changing the .print command into a .plot command, SPICE will output a crude graph made up of text characters:

In both output formats, the left-hand column of numbers represents the battery voltage at each interval, as it increases from 0 volts to 100 volts, 5 volts at a time. The numbers in the right-hand column indicate the circuit current for each of those voltages. Look closely at those numbers and you’ll see the proportional relationship between each pair: Ohm’s Law (I=E/R) holds true in each and every case, each current value being 1/5 the respective voltage value, because the circuit resistance is exactly 5 Ω. Again, the negative numbers for current in this SPICE analysis is more of a quirk than anything else. Just pay attention to the absolute value of each number unless otherwise specified.

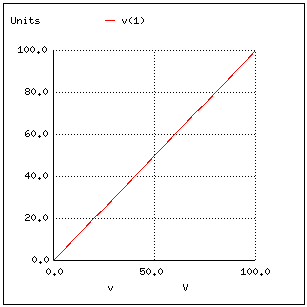

There are even some computer programs able to interpret and convert the non-graphical data output by SPICE into a graphical plot. One of these programs is called Nutmeg, and its output looks something like this:

Note how Nutmeg plots the resistor voltage v(1) (voltage between node 1 and the implied reference point of node 0) as a line with a positive slope (from lower-left to upper-right).

Whether or not you ever become proficient at using SPICE is not relevant to its application in this book. All that matters is that you develop an understanding for what the numbers mean in a SPICE-generated report. In the examples to come, I’ll do my best to annotate the numerical results of SPICE to eliminate any confusion, and unlock the power of this amazing tool to help you understand the behavior of electric circuits.