What is a Resistor?

Special components called resistors are made for the express purpose of creating a precise quantity of resistance for insertion into a circuit. They are typically constructed of metal wire or carbon, and engineered to maintain a stable resistance value over a wide range of environmental conditions. Unlike lamps, they do not produce light, but they do produce heat as electric power is dissipated by them in a working circuit. Typically, though, the purpose of a resistor is not to produce usable heat, but simply to provide a precise quantity of electrical resistance.

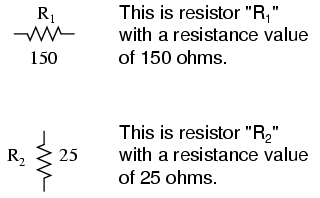

Resistor Schematic Symbols

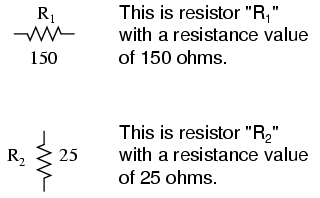

The most common schematic symbol for a resistor is a zig-zag line:

Resistor values in ohms are usually shown as an adjacent number, and if several resistors are present in a circuit, they will be labeled with a unique identifier number such as R1, R2, R3, etc. As you can see, resistor symbols can be shown either horizontally or vertically:

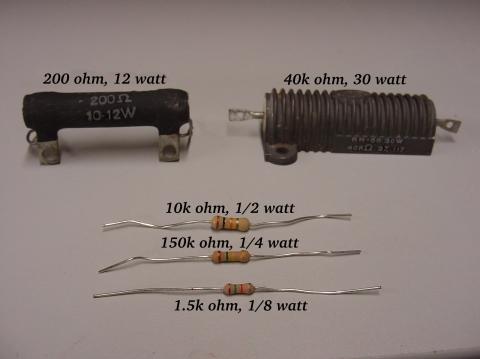

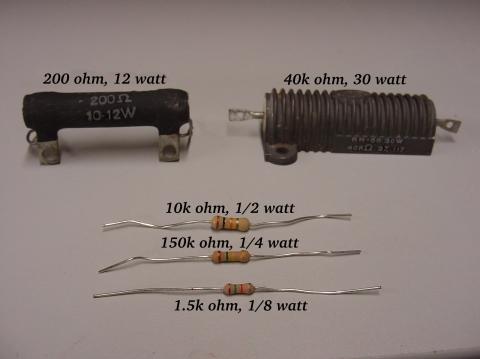

Real resistors look nothing like the zig-zag symbol. Instead, they look like small tubes or cylinders with two wires protruding for connection to a circuit. Here is a sampling of different kinds and sizes of resistors:

In keeping more with their physical appearance, an alternative schematic symbol for a resistor looks like a small, rectangular box:

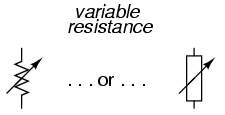

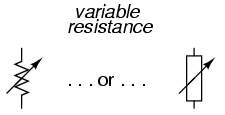

Resistors can also be shown to have varying rather than fixed resistances. This might be for the purpose of describing an actual physical device designed for the purpose of providing an adjustable resistance, or it could be to show some component that just happens to have an unstable resistance:

In fact, any time you see a component symbol drawn with a diagonal arrow through it, that component has a variable rather than a fixed value. This symbol “modifier” (the diagonal arrow) is standard electronic symbol convention.

Variable Resistors

Variable resistors must have some physical means of adjustment, either a rotating shaft or lever that can be moved to vary the amount of electrical resistance. Here is a photograph showing some devices called potentiometers, which can be used as variable resistors:

Power Rating of Resistors

Because resistors dissipate heat energy as the electric currents through them overcome the “friction” of their resistance, resistors are also rated in terms of how much heat energy they can dissipate without overheating and sustaining damage. Naturally, this power rating is specified in the physical unit of “watts.” Most resistors found in small electronic devices such as portable radios are rated at 1/4 (0.25) watt or less. The power rating of any resistor is roughly proportional to its physical size. Note in the first resistor photograph how the power ratings relate with size: the bigger the resistor, the higher its power dissipation rating. Also, note how resistances (in ohms) have nothing to do with size!

Although it may seem pointless now to have a device doing nothing but resisting electric current, resistors are extremely useful devices in circuits. Because they are simple and so commonly used throughout the world of electricity and electronics, we’ll spend a considerable amount of time analyzing circuits composed of nothing but resistors and batteries.

How are Resistors Useful?

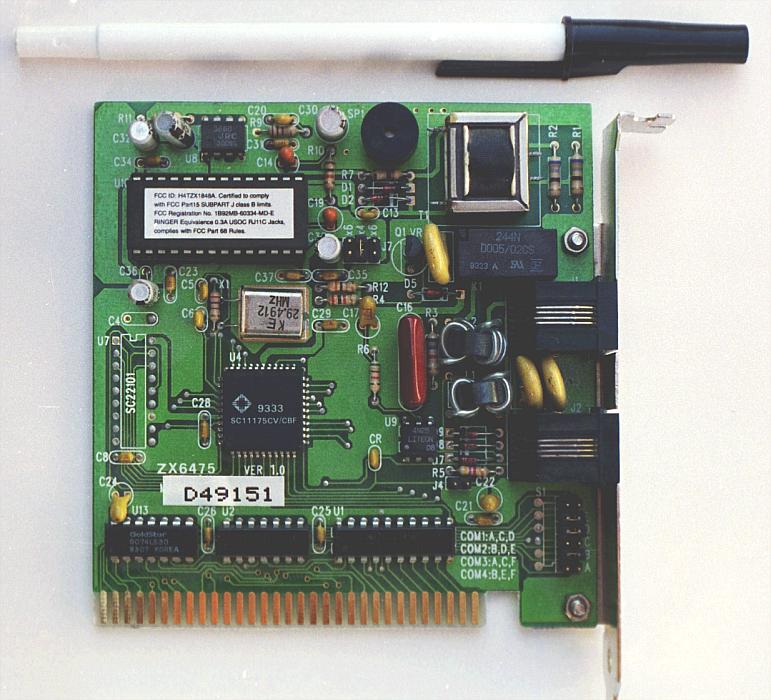

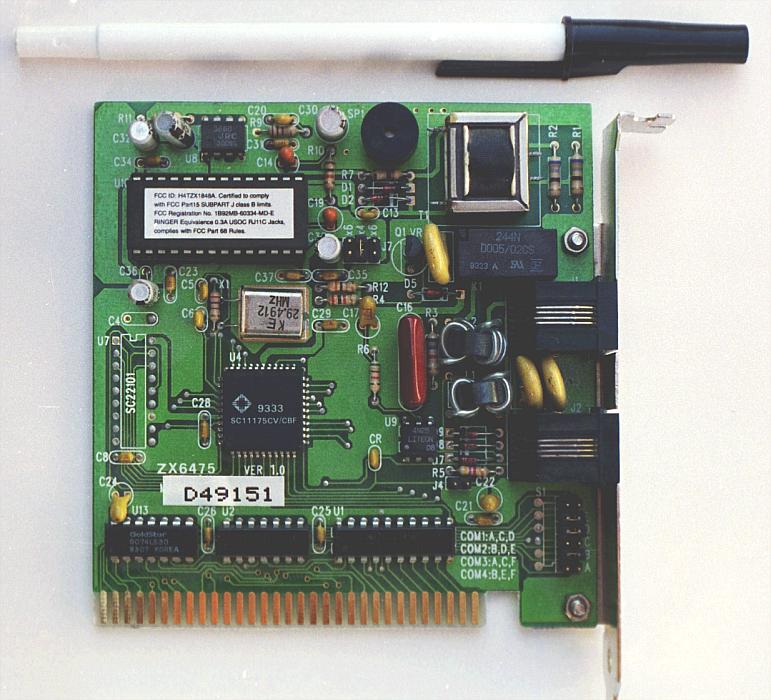

For a practical illustration of resistors’ usefulness, examine the photograph below. It is a picture of a printed circuit board, or PCB: an assembly made of sandwiched layers of insulating phenolic fiber-board and conductive copper strips, into which components may be inserted and secured by a low-temperature welding process called “soldering.” The various components on this circuit board are identified by printed labels. Resistors are denoted by any label beginning with the letter “R”.

This particular circuit board is a computer accessory called a “modem,” which allows digital information transfer over telephone lines. There are at least a dozen resistors (all rated at 1/4 watt power dissipation) that can be seen on this modem’s board. Every one of the black rectangles (called “integrated circuits” or “chips”) contain their own array of resistors for their internal functions, as well.

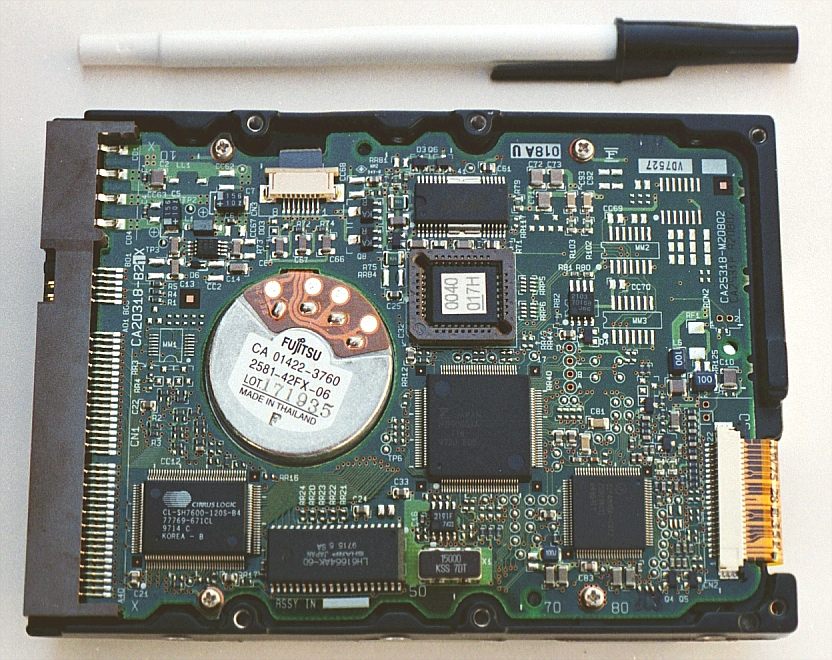

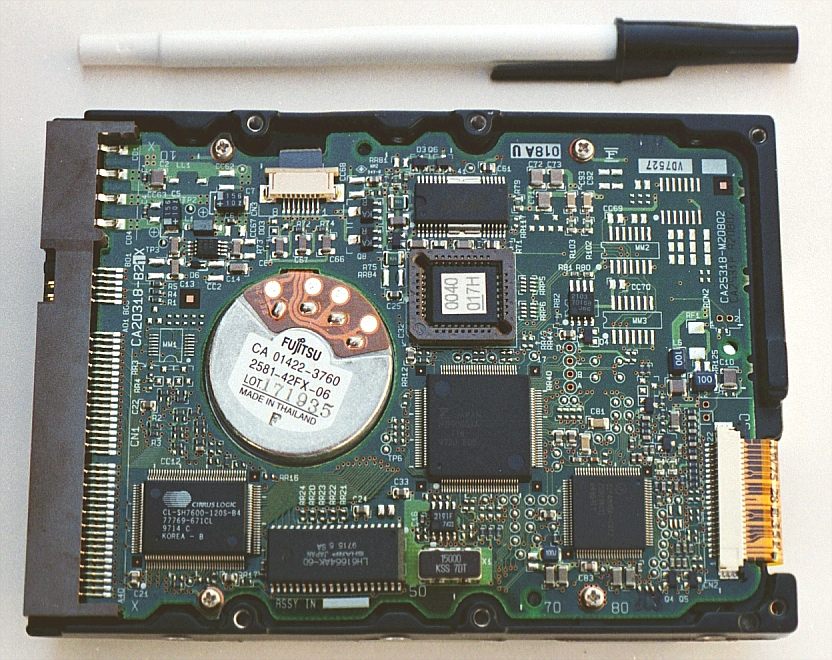

Another circuit board example shows resistors packaged in even smaller units, called “surface mount devices.” This particular circuit board is the underside of a personal computer hard disk drive, and once again the resistors soldered onto it are designated with labels beginning with the letter “R”:

There are over one hundred surface-mount resistors on this circuit board, and this count, of course, does not include the number of resistors internal to the black “chips.” These two photographs should convince anyone that resistors—devices that “merely” oppose the flow of electrons—are very important components in the realm of electronics!

“Load” on Schematic Diagrams

In schematic diagrams, resistor symbols are sometimes used to illustrate any general type of device in a circuit doing something useful with electrical energy. Any non-specific electrical device is generally called a load, so if you see a schematic diagram showing a resistor symbol labeled “load,” especially in a tutorial circuit diagram explaining some concept unrelated to the actual use of electrical power, that symbol may just be a kind of shorthand representation of something else more practical than a resistor.

Analyzing Resistor Circuits

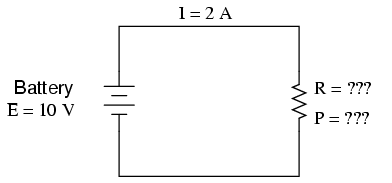

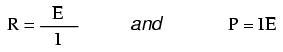

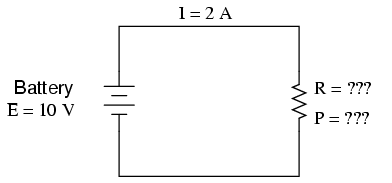

To summarize what we’ve learned in this lesson, let’s analyze the following circuit, determining all that we can from the information given:

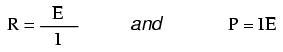

All we’ve been given here to start with is the battery voltage (10 volts) and the circuit current (2 amps). We don’t know the resistor’s resistance in ohms or the power dissipated by it in watts. Surveying our array of Ohm’s Law equations, we find two equations that give us answers from known quantities of voltage and current:

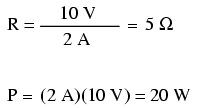

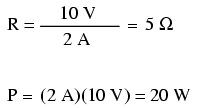

Inserting the known quantities of voltage (E) and current (I) into these two equations, we can determine circuit resistance (R) and power dissipation (P):

For the circuit conditions of 10 volts and 2 amps, the resistor’s resistance must be 5 Ω. If we were designing a circuit to operate at these values, we would have to specify a resistor with a minimum power rating of 20 watts, or else it would overheat and fail.

Resistor Materials

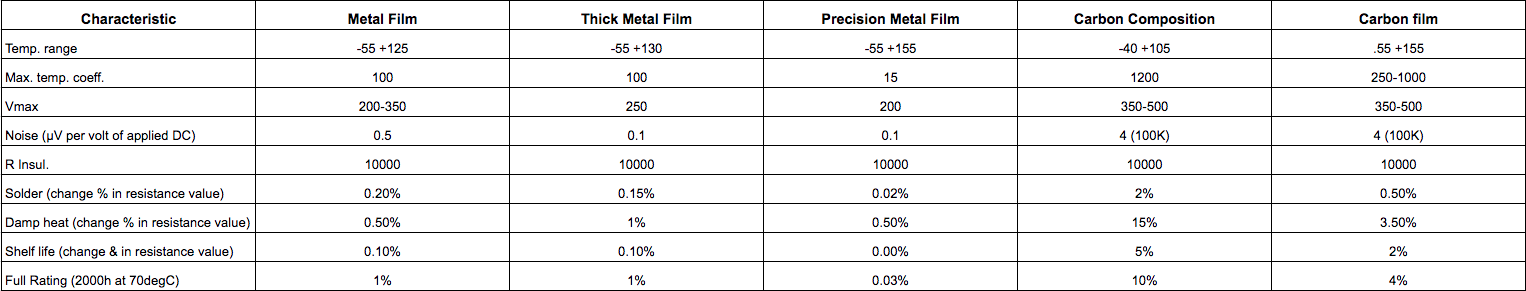

Resistors can be found in a variety of different materials, each one with its own properties and specific areas of use. Most electrical engineers use the types found below:

Wirewound (WW)

Wire Wound Resistors are manufactured by winding resistance wire around a non-conductive core in a spiral. They are typically produced for high precision and power applications. The core is usually made of ceramic or fiberglass and the resistance wire is made of nickel-chromium alloy and are not suitable for applications with frequencies higher than 50kHz. Low noise and stability with respect to temperature variations are standard characteristics of Wire Wound Resistors. Resistance values are available from 0.1 up to 100 kW, with accuracies between 0.1% and 20%.

Nichrome or tantalum nitride are typically used for metal film resistors. A combination of a ceramic material and a metal typically make up the resistive material. The resistance value is changed by cutting a spiral pattern in them film, much like carbon film with a laser or abrasive. Metal film resistors are usually less stable over temperature than wire wound resistors, but handle higher frequencies better.

Metal oxide resistors use metal oxides such as tin oxide, making them slightly different from metal film resistors. These resistors are reliable and stable and operate at higher temperatures than metal film resistors. Because of this, metal oxide film resistors are used in applications that require high endurance.

Foil

Developed in the 1960’s, the foil resistor is still one of the most accurate and stable types of resistor that you’ll find and are used for applications with high precision requirements. A ceramic substrate that has a thin bulk metal foil cemented to it makes up the resistive element. Foil Resistors feature a very low temperature coefficient of resistance.

Carbon Composition (CCR)

Until the 1960s Carbon Composition Resistors were the standard for most applications. They are reliable, but not very accurate (their tolerance cannot be better than about 5%). A mixture of fine carbon particles and non-conductive ceramic material are used for the resistive element of CCR Resistors. The substance is molded into the shape of a cylinder and baked. The dimensions of the body and the ratio of carbon to ceramic material determine the resistance value. More carbon used in the process means there will be a lower resistance. CCR resistors are still useful for certain applications because of their ability to withstand high energy pulses, a good example application would be in a power supply.

Carbon Film

Carbon film resistors have a thin carbon film (with a spiral cut in the film to increase the resistive path) on an insulating cylindrical core. This allows for the resistance value to be more accurate and also increases the resistance value. Carbon film resistors are much more accurate than carbon composition resistors. Special carbon film resistors are used in applications that require high pulse stability.

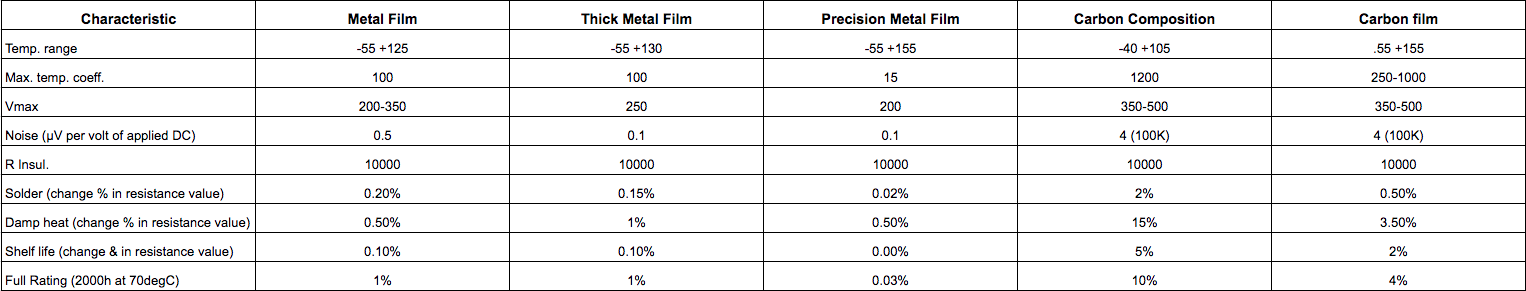

The KPIs for each resistor material can be found below:

Review

Devices called resistors are built to provide precise amounts of resistance in electric circuits. Resistors are rated both in terms of their resistance (ohms) and their ability to dissipate heat energy (watts).

- Resistor resistance ratings cannot be determined from the physical size of the resistor(s) in question, although approximate power ratings can. The larger the resistor is, the more power it can safely dissipate without suffering damage.

- Any device that performs some useful task with electric power is generally known as a load. Sometimes resistor symbols are used in schematic diagrams to designate a non-specific load, rather than an actual resistor.