2.5: Develop Concepts

- Page ID

- 9514

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Step 3: Developing Concepts

Concept development is a process of developing ideas to solve specified design problems. The concepts are developed in phases, from formless idea to precise message in an appropriate form with supportive visuals and content. Once you have done your research and understand exactly what you want to achieve and why, you are ready to start working on the actual design. Ideally, you are trying to develop a concept that provides solutions for the design problem, communicates effectively on multiple levels, is unique (different and exciting), and stands out from the materials produced by your client’s competitors.

Generate, test, and refine ideas

A good design process is a long process. Designers spend a great deal of time coming up with ideas; editing, revising, and refining them; and then evaluating their results every time they try something. Good design means assessing every concept for effectiveness.

The design process looks roughly like this:

- Generating a concept

- Refining ideas through visual exploration

- Preparing rough layouts detailing design direction(s)

- Setting preliminary specifications for typography and graphic elements such as photography, illustration, charts or graphs, icons, or symbols

- Presenting design brief and rough layouts for client consideration

- Refining design and comprehensive layouts, if required

- Getting client approval of layouts and text before the next phase

Developing Effective Concepts

A concept is not a message. A concept is an idea that contextualizes a message in interesting, unique, and memorable ways through both form and design content.

A good concept reinforces strategy and brand positioning. It helps to communicate the benefits of the offer and helps with differentiation from the competition. It must be appropriate for the audience, facilitating communication and motivating that audience to take action.

A good concept provides a foundation for making visual design decisions. For example, Nike’s basic message, expressed by its tagline, is “Just Do It.” The creative concept Nike has used since 1988 has been adapted visually in many ways, but always stays true to the core message by using images of individuals choosing to take action.

“It was a simple thing,” Wieden recalls in a 2009 Adweek video interview in which he discusses the effort’s genesis. Simplicity is really the secret of all “big ideas,” and by extension, great slogans. They must be concisely memorable, yet also suggest something more than their literal meanings. Rather than just putting product notions in people’s minds, they must be malleable and open to interpretation, allowing people of all kinds to adapt them as they see fit, and by doing so, establish a personal connection to the brand (Gianatasio, 2013).

A good concept is creative, but it also must be appropriate. The creativity that helps develop effective, appropriate concepts is what differentiates a designer from a production artist. Very few concepts are up to that standard — but that’s what you should always be aiming for.

In 1898, Elias St. Elmo Lewis came up with acronym AIDA for the stages you need to get consumers through in order for them to make a purchase. Modern marketing theory is now more sophisticated, but the acronym also works well to describe what a design needs to do in order to communicate and get people to act.

In order to communicate effectively and motivate your audience, you need to:

A — attract their attention. Your design must attract the attention of your audience. If it doesn’t, your message is not connecting and fulfilling its communication intent. Both the concept and the form must stand out.

I — hold their interest. Your design must hold the audience’s interest long enough so they can completely absorb the whole communication.

D — create a desire. Your design must make the audience want the product, service, or information.

A — motivate them to take action. Your design must compel the audience to do something related to the product, service, or information.

Your concept works if it makes your audience respond in the above ways.

Generating Ideas and Concepts from Concept Mapping

You can use the information in a concept map to generate additional concepts for your project by reorganizing it. The concept tree method below comes from the mind-mapping software blog (Frey, 2008)

- Position your design problem as the central idea of your mind map.

- Place circles containing your initial concepts for solving the problem around the central topic.

- Brainstorm related but non-specific concepts, and add them as subtopics for these ideas. All related concepts are relevant. At this stage, every possible concept is valuable and should not be judged.

- Generate related ideas for each concept you brainstormed in step 3 and add them as subtopics.

- Repeat steps 3 and 4 until you run out of ideas.

Applying Rhetorical Devices to Concept Mapping

After you have placed all your ideas in the concept map, you can add additional layering to help you refine and explore them further. For example, you can use rhetorical devices to add context to the concepts and make them come alive. Rhetoric is the study of effective communication through the use and art of persuasion. Design uses many forms of rhetoric — particularly metaphor. If you applied a metaphor-based approach to each idea in your concept map, you would find many new ways to express your message.

Rhetorical Devices Appropriate for Communication Design

Allusion is an informal and brief reference to a well known person or cultural reference. In the magazine cover linked below, an allusion is used to underline the restrictive nature of the burqa, a full body cloak worn by some Muslim women, by applying it to Sarah Jessica Parker, an actor whose roles are primarily feminist in nature. (Harris, 2013)

Follow the link to see an example: Marie Claire Cover

Amplification involves the repetition of a concept through words or images, while adding detail to it. This is to emphasize what may not be obvious at first glance. Amplification allows you to expand on an idea to make sure the target audience realizes its importance. (Harris, 2013)

Follow the link to see an example: Life’s too short for the wrong job Marketing Campaign

Analogy compares two similar things in order to explain an otherwise difficult or unfamiliar idea. Analogy draws connections between a new object or idea and an already familiar one. Although related to simile, which tends to employ a more artistic effect, analogy is more practical; explaining a thought process, a line of reasoning, or the abstract in concrete terms. Because of this, analogy may be more insightful. (Harris, 2013)

Follow the link to see an example: WWF Lungs Before It’s Too Late

Hyperbole is counter to understatement. It is a deliberate exaggeration that is presented for emphasis. When used for visual communication, one must be careful to ensure that hyperbole is a clear exaggeration. If hyperbole is limited in its use, and only used occasionally for dramatic effect, then it can be quite attention grabbing.

Follow the link to see an example: Final Major Project by Mark Studio

A written example would be: Thereare a thousand reasons why more research is needed on solar energy.

Or it can make a single point very enthusiastically: I said “rare,” not “raw.” I’ve seen cows hurt worse than this get up and walk.

Hyperbole can be used to exaggerate one thing to show how it differs from something to which it is being compared: This stuff is used motor oil compared to the coffee you make, my love.

Hyperbole is the most overused rhetorical device in the world (and that is no hyperbole); we are a society of excess and exaggeration. Handle it like dynamite, and do not blow up everything you can find (Harris, 2013).

Metaphor compares two different things by relating to one in the same terms commonly used for the other. Unlike a simile or analogy, metaphor proposes that one thing is another thing, not just that they are similar (Harris, 2013).

Follow the link to see an example: Ikea Bigger Storage Idea

Metonymy is related to metaphor, where the thing chosen for the metaphorical image is closely related to (but not part of) that with which it is being compared. There is little to distinguish metonymy from synecdoche (as below). Some rhetoricians do not distinguish between the two (Harris, 2013).

Follow the link to see an example: London Logo

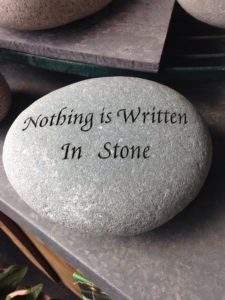

Oxymoron is a paradox presented in two words, in the form of an adjective and noun (“eloquent silence”), or adverb-adjective (“inertly strong”), and is used to impart emphasis, complexity, or wit (Harris, 2013). See Figure 2.3 for another example.

Personification attributes to an animal or inanimate object human characteristics such as form, character, feelings, behaviour, and so on. Ideas and abstractions can also be personified. For example, in the poster series linked below, homeless dogs are placed in environments typical of human homelessness (Harris, 2013).

Follow the link to see an example: Manchester Dogs’ Home Street Life

Simile is a comparison of one thing to another, with the two being similar in at least one way. In formal prose, a simile compares an unfamiliar thing to a familiar thing (an object, event, process, etc.) known to the reader. (Harris, 2013)

Follow the link to see an example: Strong Handle Billboard

Synecdoche is a type of metaphor in which part of something stands for the whole, or the whole stands for a part. It can encompass many forms such that any portion or quality of a thing is represented by the thing itself, or vice versa (Harris, 2013).

Follow the link to see an example: A Global Warming Poster

Understatement deliberately expresses a concept or idea with less importance as would be expected. This could be to effect irony, or simply to convey politeness or tact. If the audience is familiar with the facts already, understatement may be employed in order to encourage the readers to draw their own conclusions (Harris, 2013).

For example: instead of endeavouring to describe in a few words the horrors and destruction of the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco, a writer might state: The 1906 San Francisco earthquake interrupted business somewhat in the downtown area.

Follow the link to see an example: Nike’s Just Do It

An excellent online resource for exploring different rhetorical devices is “A Handbook of Rhetorical Devices” (Harris, 2013). The definitions above have been paraphrased from this site.

Developmental Stages of Design

No design work should ever be done without going through an iterative development process in which you try out different ideas and visual approaches, compare and evaluate them, and select the best options to proceed with. This applies to both form and content.

The development of the concept starts with brainstorming as wide a range of ideas as possible, and refining them through a number of development stages until you are left with those that solve the communication problem most effectively.

The development of graphic forms starts with exploring a wide range of styles, colours, textures, imagery, and other graphic devices and refining them through development stages until you are left with those that best reinforce the concept and message.

The development process starts with thumbnails and works through rough layouts and comprehensives to the final solution. Thumbnails are small, simple hand-drawn sketches, with minimal information. These are intended for the designer’s use and, like concept maps, are visuals created for comparison. These are not meant to be shown to clients.

Their uses include:

- Concept development and visualization of ideas

- Preliminary evaluation of content (they allow you to sift and sort ideas quickly and effectively)

- Preliminary evaluation of form (value studies, compositional studies, potential placement of elements)

- Note-taking (a tool to record verbal or visual information quickly and accurately)

Quantity is very important in thumbnails! The idea is to get as many ideas and options down as possible.

Designers typically take one of two approaches when they do thumbnails: they either brainstorm a wide range of ideas without exploring any of them in depth, or they come up with one idea and create many variations of it. If you use only one of these approaches, force yourself to do both. Brainstorm as many ideas as possible, using a mix of words and images. The point here is the quantity of ideas — the more the better. Work fast and don’t judge your work yet.

Once you have a lot of ideas, take one you think is good and start exploring it. Try expressing the same idea with different visuals, from different points of view, with different taglines and emotional tones. Make the image the focal point of one variation and the headline the focal point of another. The purpose here is to try as many variations of an idea as possible. The first way of expressing an idea is not necessarily the best way, much like the first pancake is not usually the best.

After you’ve fully explored one idea, choose another from your brainstorming session and explore it in the same way. Repeat this with every good idea.

Roughs are exactly that — rough renderings of thumbnails that explore the potential of forms, type, composition, and elements of your best concepts. Often a concept is explored through the development of three to five roughs. These are used to determine exactly how all of the elements will fit together, to provide enough information to make preliminary evaluation possible, and to suggest new directions and approaches.

The rough:

- Uses simple, clean lines and basic colour palettes.

- Accurately renders without much detail (the focus is on design elements, composition, and message)

- Includes all of the visual elements in proper relationship to each other and the page

Comps are created for presenting the final project to the client for evaluation and approval. The comp must provide enough information to make evaluation of your concept possible and to allow final evaluation and proofing of all content.

The comp:

- Is as close as possible to the final form and is usually digital

- May use final materials or preliminary/placeholder content if photographs or illustrations are not yet available

Hand-drawn or Digital?

Comps might be hand-drawn when you are showing a concept for something that doesn’t yet exist, such as a product that hasn’t been fabricated, a structure that hasn’t been built, or to show a photographer how you want material to be laid out in a photograph that has not yet been taken. Although you could create these comps digitally, it’s often more cost effective to create a sketch.

Designers sometimes create hand-drawn comps in order to avoid presenting conceptual work that looks too finished to a client, so they will not be locked into a particular approach by the client’s expectations.

Even in this digital age, you should draw all thumbnails by hand (using pen, pencil, or tablet) for the following reasons:

- You don’t have to make time-wasting decisions that you shouldn’t be making at this early stage (e.g., what typeface should I use? what colour should this be?)

- It’s much faster than doing it digitally.

- Work done on a computer tends to look finished and professional, and this can trick you into thinking an idea is better than it is.

- The technology of a tool tends to define the way it is used. If you are using a computer, you will tend to come up with solutions that can be executed only on a computer, and that limits your creative options. For example, would you think of creating an illustration from coloured paper if you were using the computer?

- Hand-drawn sketches provide a paper trail that shows your concept development process and can be presented in case studies to reveal your entire design process in a more personal and engaging way.

Media Attributions

- nothing-is-written-in-stone-527756_1920 by SBM © Public Domain