7.4: Race and the Courts

- Page ID

- 16138

Los Angeles police officers beat a black man named Rodney King, after a car chase in 1991. The incident was videotaped by a citizen, documenting the amount of force used by the officers. The Black community had complained about police brutality for many years and believed there was now verifiable proof of police brutality. All four officers involved in the incident were criminally charged, however at the trial in state court, the jury acquitted the four officers of using excessive force. Following the verdict, civil unrest ensued in Los Angeles, resulting in riots, looting, arson and assaults.

However, the story doesn't end there, the four officers were tried for civil rights violations in federal court, resulting in the conviction of two officers. Even with the guilty verdict, many in the Black community and in other minority communities suggest the case indicates the difficulty people of color have obtaining a fair outcome from the criminal justice system. Many feel officers unjustly stop and use excessive force when dealing with minorities. This injustice they say starts with officers but continues through the whole criminal process. Many say the whole system needs reform.

Some who believe the justice system in its totality is racist often cite the incarceration rate of Black and Hispanic males. The Bureau of Justice Statistics analysis indicate if current incarceration rates remain unchanged, 32 percent of black males and 17 percent of male Hispanic males born in 2001 will be subject to incarceration in prison during their lifetime. For Caucasian males, the percentage is much lower at 6 percent. Black Americans represent approximately 12 percent of the United States population, however, represent 40 percent of all prison inmates and 42 percent of those sentenced to death.

So, the question is - Do these statistics prove racism in the criminal justice system or are they from other causes? Social scientists, politicians, law enforcement agencies, civil rights advocates and media commentator have argued over the meaning of these statistics. Some argue racism in the system is to blame for the statistics, others argue its due to poverty, or personal responsibility, or acceptance of criminal behavior. The debate continues, however maybe the answer is not just one thing, but the answer is “All of the above.”

In a 1975 article, titled “White Racism, Black Crime, and American Justice.” Criminologist Robert Staples argued that discrimination dominates the American justice system. His theory was based on the notion that the legal system was created by white men to protect white people and their assets. By doing so the intended result was to keep black people subjugated. Staples believed that the entire judicial system was racist due to poor legal representation by public defenders for black defendants, juries who were bias toward blacks and judges who sentenced blacks to harsher sentences.

Sociologist William Wilbanks rejected Staples discrimination argument in the 1987 book, titled “The Myth of a Racist Criminal Justice System.” Wilbanks researched numerous studies which reported statistical inequalities in arrest rates and imprisonments between whites and blacks in the criminal justice system. He discovered that the inequalities came from factors such as the defendant’s criminal history and poverty, not from racial discrimination. Others have argued the apparent inequalities in the criminal justice process are related more due to poverty than race. Crimes such as robbery and assault, which are significant in the statistics, are usually committed by people from poor backgrounds. Today, approximately 39 percent of all Blacks and Hispanics live below the official poverty line, compared to approximately 9 percent of all whites.

Street Level Arrest

In 2010, Black Americans accounted for a third of the arrests for violent crimes. This surpasses the numbers of Black Americans in the population. Those who dispute Robert Staples argument of racism point out the percentage is consistent to reports from the National Crime Victimization Survey. This survey interviews thousands of victims of crime each year. The percentage of victims who say the suspect was black closely matches the percentage of Black Americans arrested. However, different studies of arrest indicate that police are involved in some discrimination against members of racial and ethnic minorities.

It is clear that Black Americans have a higher arrest rate for drug possession and trafficking, disproportionate to the number of Black Americans within the population. Blacks are only 12 percent of the population and approximately13 percent of drug users, but Black Americans represent nearly a third of people arrested in 2010. Those that argue racism point to the use of “racial profiling.” It is alleged that police, using drug courier profiles stop black males for minor driving or vehicle mechanical violations.

In New Jersey, a review of documented traffic stops between 1989 and 1991 determined that 72 percent of drivers stopped and arrested were Black Americans, while only 14 percent of vehicles had a black driver or occupant. New Jersey data for the same period indicated that blacks and whites had the same rate of traffic violations. A few years later a Maryland study indicated similar results: 17 percent of vehicle code violators were black, but 72 percent of those searched were black. These types of law enforcement practices may suggest blacks will be involved in the criminal justice system more rapidly than whites.

In some states, Black Americans are released quicker than White Americans after arrest. A significant amount of those arrests are for less serious offenses such as prostitution, gambling, and public drunkenness. The meaning of this is up for debate. Those refuting the racism argument say that police and prosecutors are more likely to treat Black Americans more lenient than White Americans. Those who argue racism is rampant in the criminal justice system argue it is evidence Black Americans are more likely to be arrested on insufficient evidence or harassed by police because of racism, or at a minimum indicates bias.

Those who believe the police have too much authority and utilize racist practices argue the courts contribute to the perceived racist practices. The argument is the courts have given officers too much discretion when it comes to police practices and establishing probable cause. Also, the argument suggests the officers state of mind should be relevant in contacting citizens.

In the case of Whren v. United States Whren was driving in a 'high drug area.' Some plainclothes officers, while patrolling the neighborhood in an unmarked vehicle, noticed Whren sitting in a truck at an intersection stop-sign for an usually long time. Suddenly, without signaling, Whren turned his truck and sped away. Observing this traffic violation, the officers stopped the truck. When they approached the vehicle, the officers saw Whren holding plastic bags of crack cocaine. Whren was arrested on federal drug charges. Before trial, Whren moved to suppress the evidence contending that the officers used the traffic violation as a pretext for stopping the truck because they lacked either reasonable suspicion or probable cause to stop them on suspicion of drug dealing.

In a unanimous decision the United States Supreme Court held that as long as officers have a reasonable cause to believe that a traffic violation occurred, they may stop any vehicle. In the present case, the officers had reasonable cause to stop the petitioners for a traffic violation since they sped away from a stop sign at an 'unreasonable speed' and without using his turn signal. Thus, since an actual traffic violation occurred, the ensuing search and seizure of the offending vehicle was reasonable, regardless of what other personal motivations the officers might have had for stopping the vehicle.

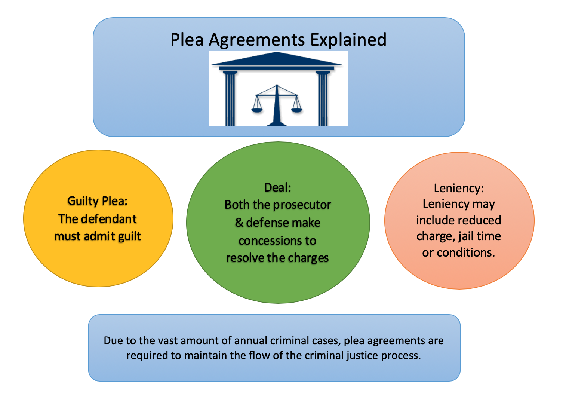

Plea Bargains and the Courts

In the United States, 90-97% of all criminal cases are resolved through the plea-bargaining process. The first step of the process is arraignment in which the defendant and defense counsel are notified of the charges, most often the maximum charges the district attorney is alleging based on the crime committed. Crime reports are provided to counsel to evaluate the initial strength of the case. After this initial hearing, a plea-bargaining process can begin. The plea bargain process in California usually consists of the district attorney, defense counsel, the judge and possibly a probation officer to provide criminal history and sentencing recommendations depending on the charges.

There is some concern that plea bargaining can have racial disparity and those of color are treated differently or more severely than whites. Research has been conducted to determine if there is significant disparity in the way Hispanics, black and whites are treated in the plea-bargaining process. One key consideration is how charges are treated from the initial filing of charges in the D.A. complaint and the plea charges agreed upon during the plea agreement process. Does race factor into how charges are reduced during the plea-bargaining process?

In a 2018 study of this process, the author Carlos Berdejo found there was racial disparity during the plea-bargaining process. “White defendants are twenty-five percent more likely than black defendants to have their principal initial charge dropped or reduced to a lesser crime. As a result, white defendants who face initial felony charges are less likely than black defendants to be convicted of a felony.” What this means, is white defendants who were initially charged with a felony or serious crime are more likely to have the charge reduced to a misdemeanor or lessor crime. He also found that this disparity is even greater at the lower level crimes (misdemeanor) in which offender of color were more likely to serve jail time for minor offenses and white offenders received other sanctions.

In the United States approximately 90 percent of all criminal cases will never go to trial. The prosecutor and defense attorney enter into negotiations, and if an agreement can be reached and the judge agrees; the defendant will plead guilty, often to a lesser charge. The United States Sentencing Commission conducted a study in 1990 which reviewed 1,000 cases. The commission determined that whites received a better deal in the plea bargains. Twenty-five percent of whites had their charges reduced through the plea-bargaining process, compared to 18 percent of blacks, and 12 percent of Hispanics.

In 1991, a San Jose newspaper conducted a comprehensive review of 700,000 criminal cases in California, spanning 10-years. The Mercury News reported that 33% of the white adults who were charged, but had no prior record, were able to get felony charges reduced. Compared to Black Americans and Hispanic Americans with no prior records who were only successful in reducing charges 25% of the time. The news paper's conclusions did not suggest intentional racism for these differences. The author did suggest that cultural fears and insensitivity could have been contributing factors to the differences. The article noted that at the time 80 percent of all California prosecutors and judges are white, while more than 60 percent of those arrested are non-white. The newspapers reporting made it clear the author and the editors believed that implied bias was contributing to the perceived inequities in the plea-bargaining process.

Jury Selection and Trial

For the criminal cases not resolved through the plea-bargaining process, they proceed to the jury trial. Things that need to be considered is how the jury selection process can affect the outcome. A key to the American criminal process is innocent until proven guilty and a trial by a jury of your peers. But is this occurring? In this section we examine the jury selection process and the affect it has on the outcome of a trial.

Cornell University Law Professor Sheri Johnson reviewed twelve mock-jury studies. She determined the race of the defendant directly affected the juries’ determination of guilt. In the mock trial, identical presentations and facts were simulated, sometimes with white defendants and sometimes with a black defendant. Professor Johnson concluded white jurors were more likely to find a black defendant guilty than a white defendant, even though the mock trials were based on the same crime and the same evidence.

The results discovered black jurors displayed reverse bias. Black jurors found white defendants guilty more than black defendants. Additionally, the race of the victim in the case affected both groups. White jurors determined white defendants less culpable if the victim was black. Likewise, black jurors found black defendants less culpable if the victim were white. Based on these mock-jury results, jurors of both races displayed biased behavior. So, the major question taken away from these results, is the criminal justice system racially unfair? The researchers believed the juror bias was not conscious. They attributed a guilty verdict on the basis of race seemed to be subconscious. The researchers surmised jurors were unlikely to be aware of their bias during the process.

The U.S. Supreme Court has attempted to promote racially mixed juries by prohibiting prosecutors and defense lawyers from using peremptory challenges to remove potential jurors based on race. In the case of Batson v. Kentucky (1986) Batson, a black man, was on trial charged with second-degree burglary and receipt of stolen goods. During the jury selection, the prosecutor used his peremptory challenges to remove the four black persons on the jury panel, resulting in a jury composed of all white people. Batson was convicted on both of the charges against him.

The United States Supreme Court found that the prosecutor's actions violated the Sixth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution. Relying heavily on precedents set in Strauder v. West Virginia (1880) and Swain v. Alabama (1965), Justice Powell held that racial discrimination in the selection of jurors not only deprives the accused of important rights during a trial, but also is devastating to the community at large because it "undermines public confidence in the fairness of our system of justice." Without identifying a "neutral" reason why the four blacks should have been excluded from the jury, the prosecutor's actions were in violation of the Constitution.

Justice Thurgood Marshall called for ending the use of peremptory challenges altogether. Justice Marshall said, only by banning peremptory challenges can racial discrimination in jury selection be ended. Six year later in the case of Georgia v. McCollum (1992) the Supreme Court would address race and peremptory challenges once more. White defendants, Thomas McCollum, William Joseph McCollum, and Ella Hampton McCollum were charged with assaulting two black individuals. Before the criminal trial, the prosecution moved to bar the defense from using its peremptory challenges to eliminate black people from the juror pool. The term "peremptory challenge" refers to the right to reject a potential juror during jury selection without giving a reason. The trial judge denied the prosecution's motion, and, when the prosecution appealed, the Georgia Supreme Court affirmed the trial judge's decision.

The United States Supreme Court found that the exercise of peremptory challenges in a racially discriminatory manner not only violates the rights of potential jurors, but also undermines the integrity of the judicial system. Since the Court also determined that a peremptory challenge did constitute state action, it found the use of peremptory challenge for the purpose of racial discrimination to be a breach of the Equal Protection Clause. Consequently, the decision of the Georgia Supreme Court was reversed.

Even after the Supreme Court’s rulings it can be challenging to enforce the courts mandates or ensure prosecutors and defense attorneys do not attempt to manipulate the judicial system. In the case of Miller - El v. Dretke (2003) the United States Supreme Court reviewed a case involving a black Texas death-row inmate. Miller-El alleged the prosecution in his capital murder trial violated the 14th Amendment's equal protection clause by excluding 10 of 11 blacks from the jury. The jury convicted Miller-El and he was sentenced to death. State courts rejected Miller-El's appeals and ruled Miller-El failed to meet the requirements for proving jury-selection discrimination outlined by the U.S. Supreme Court in Batson v. Kentucky. Miller-El then appealed to a federal district court. The district court rejected Miller-El's appeal and ruled the court must defer to the state courts' acceptance of prosecutors' race-neutral justifications for striking potential jurors. The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed and ruled a federal court could only grant an appeal if the applicant made a substantial showing of the denial of a constitutional right.

In a 6-3 opinion delivered by Justice David Souter, the Court held that Miller-El deserved to win his appeal because the jury selection in his case violated the Fourteenth Amendment's equal protection clause. The Court began by noting that the prosecutors used peremptory strikes to exclude 91 percent of the eligible black prospective jurors, "a disparity unlikely to have been produced by happenstance." After comparing two eliminated black prospective jurors with similar white jurors who were not eliminated, the Court concluded that the "selection process was replete with evidence that prosecutors were selecting and rejecting potential jurors because of race." The Court further concluded that Texas' jury selection manual, both in this case and generally, tended to allow prosecutors to read disparate questions to prospective jurors depending on whether they were black or white.

Court Sentencing

Studies have determined that once convicted by a court Black Americans are more likely than White Americans to be incarcerated. Additionally, sentences were longer for blacks than for whites. The study suggests that people involved in the sentencing process like probation officers, judges, and parole boards are utilizing allowed discretion in sentencing or probation and parole decisions such a way that is discriminatory toward Black Americans.

Unintended discrimination may take place at many points in the criminal justice process. Probation officers prepare pre-sentencing reports for a judge. The judge utilizes the reports to help making decisions related to sentencing. Pre-sentencing reports typically include information on the criminal’s prior record, family background, education, marital status, and employment history. Many African Americans convicted of crimes come from lower sociology-economic background with single parent homes, many with substance abuse problems. The criminals pre-sentencing reports contain information such as trouble in school and family problems which the judges cannot relate to. The study suggests these factors may persuade some judges to sentence them to more sever sentences. However, it is important to note that the criteria for whether to impose the low, middle, or upper term in sentencing is based on the aggravating or mitigating factors of the offense and not the socio-economic factors of the offender.

A survey of studies on discrimination in the criminal justice system discovered that much of the differences in sentencing can be determined by the arrested persons criminal charges and prior criminal activity of those. The survey concluded there was no evidence of bias throughout the criminal justice system, however examination of specific jurisdictions and courts did find evidence that suggests racial bias in a significant number of cases.

When reviewing drug offenses separately, some federal sentencing practices had the effect of discriminating against Black Americans. Federal laws created harsher mandatory sentences for crack cocaine, which was popular in poor black communities. Powder cocaine, which had lower sentencing structure was typically consumed in wealthier communities. For example, selling 28 grams of crack cocaine a suspect would be sentenced to a mandatory minimum sentence of five years, even if it was the suspects first offense. To be sentenced for a minimum five years, a suspect would have to be convicted of selling 500 grams of powder cocaine. Because a greater majority of crack cocaine users are black while powder cocaine users white, the result of the law had an adverse effect on the black community.

In 2010, the United States Congress passed the “Fair Sentencing Act.” This law repealed the mandatory minimum sentences and eliminated the discrepancy between crack and powder cocaine possession and sales. Additionally, in 2012, the United States Supreme Court addressed the law in Dorsey v. United States. The Court held that the Fair Sentencing Act's (FSA) lower minimum sentences apply to offenders sentenced after the FSA's passage, even for crimes committed before its passage. In the Court's opinion, Congress clearly intended for the sentencing guidelines to apply to pre-Act offenders. The FSA is intended to create uniformity and proportionality in sentencing, a goal that would be undermined by applying the old sentencing guidelines after the Act's passage. Instead, applying the old sentencing guidelines would create the exact sentencing disparities that Congress tried to prevent with the FSA.

In this activity, click here to access the Community Court website. This will provide you with information on how successful community courts can be launched in your community.

Answer the following questions based on the above reading:

- Thinking about the community you live in, identify a specific population you believe would best be targeted for community policing and why?

- Now identify the stakeholder or board that would provide input on how the program would be run. Why did you choose these people?

- Who would oversee the process? What checks and balances would be in place to ensure community safety?

- Present your finding to the class.

- Peer review of each program, each group will provide feedback on the project design.