1.18: Perspective- Household Foodwork

- Page ID

- 21000

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Mary Anne Martin is a White settler woman and adjunct faculty member in the Master of Arts in Sustainable Studies program at Trent University. Her interests include household food insecurity, the impact of community-based food initiatives, and intersections between gender and food systems. She actively participates in food policy initiatives and is dedicated to fostering social change through campus-community collaborations.

Michael Classens is a White settler man and Assistant Professor in the School of the Environment at University of Toronto. He is broadly interested in areas of social and environmental justice, with an emphasis on these dynamics within food systems. As a teacher, researcher, learner, and activist he is committed to connecting theory with practice, and scholarship with socio-ecological change. Michael lives in Toronto with his partner, three kids, and dog named Sue.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Explain the concept, framing, and dynamics of household foodwork

- Name ways in which household foodwork is organized through structures of inequity such as gender, race, and class.

- Articulate ways in which individuals’ foodwork and food consumption are inextricable from broader structures and interdependencies.

- Identify possible paths towards a fairer food system.

Introduction

How much thought do you give to activities like getting groceries, making meals, and washing dishes? These forms of household foodwork, while so necessary on an ongoing basis for households to survive and for society to function, nonetheless tend to go relatively unnoticed and undervalued, both in the home and well beyond it. They can seem unremarkable, taken-for-granted, almost invisible—at least until one has to do them. And because this work isn’t measured or counted, it doesn’t count in national accounting systems of economic value, like the Gross Domestic Product (GDP)—which, in turn, can make this work even less noticeable in homes and communities.[1]

Household foodwork is defined here as all the tasks and effort involved for a household in planning for, acquiring, preparing, serving, consuming, cleaning up, storing, and disposing of food. It includes not only more obvious, practical tasks (e.g., food shopping or washing dishes), but also cognitive tasks (e.g., determining what food to buy or how to use a recipe), emotional work (e.g., responding to household members’ needs for nurturing or celebration through food) and managerial work (e.g., enlisting the assistance of others with foodwork). The way that households are organized (e.g., nuclear family members, extended family members, individuals living on their own, collections of roommates) affects what household foodwork looks like.

Overall, household foodwork activities revolve primarily around the home and occur on an unpaid basis. However, they are by no means confined to just domestic spaces or non-monetary practices. Feeding households frequently means engaging with businesses (by phone, online, or in public spaces) to procure food and related goods and services. More than ever, people today buy their food instead of growing or making it.[2] This means that the kinds of work that were more common 150 years ago—like growing vegetables, raising chickens, preserving jams, baking bread, or cooking meals—are more often outsourced to those such as farmers, processors, retailers, restaurants, and, increasingly, takeout delivery services. Our ability to eat almost anything relies on other people.

Food for Foodwork

It may go without saying, but at a bare minimum, household foodwork requires food and the means to acquire it. Even though food is one of the most basic human needs, it is still treated as a commodity. That is, food is usually bought and sold, like so many less-important things in our lives. This means, of course, that people with money are seen as “deserving” food, but those without money aren’t. Instead, people who can’t afford food often live with food insecurity, “the inadequate or insecure access to food because of financial constraints.”[3] They may worry a lot about affording food, go without nutritious food, or skip meals entirely—even though many countries have committed to the right of all their citizens to adequate food.[4]As one example, in Canada, a prosperous country, 12.7% of households (or at least 4.4 million people) were living with food insecurity before the global COVID pandemic, while 10.5% of households, or over 35 million people in the U.S., were food insecure.[5]

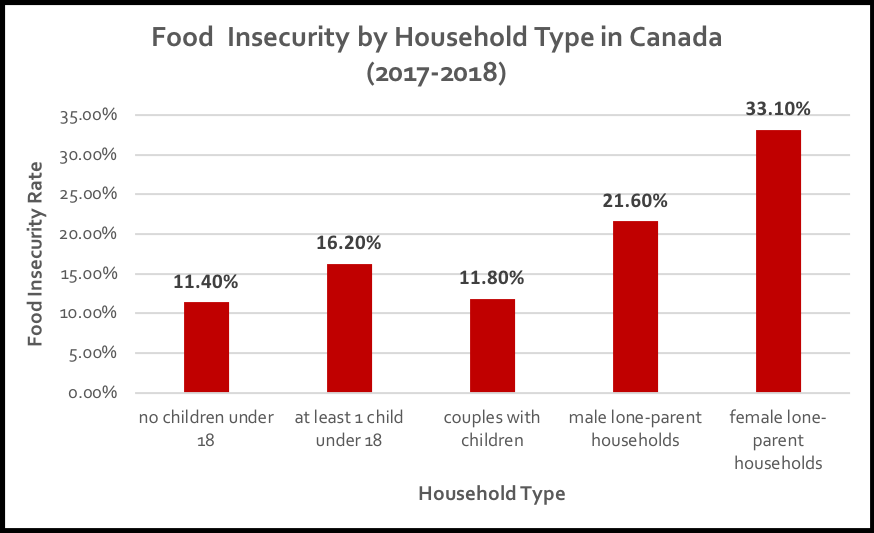

Paradoxically, as Figure 1 illustrates, some of those with the utmost responsibility for household foodwork, such as parents, often don’t have adequate food with which to accomplish it. In fact, in Canada, the presence of children under the age of 18 raises a household’s risk of food insecurity from 11.4% to 16.2%. Households of lone parents, in particular, experience much higher rates of food insecurity. In fact, 21.6% of male lone-parent households and an astounding 33.1% of female lone-parent households experience food insecurity.[6] Having children means both added expenses and more challenges in maintaining stable and well-paid employment. Furthermore, raising children on one’s own typically means that there is no additional adult to earn an income for a household. And women are much more likely to earn less than men and to assume primary caregiving roles for children.[7] Overall, parenting status, partner status, and gender all affect food insecurity. That is, who you are, who you live with, and who you care for all affect whether your food needs will be met. The individualized assumption that every person should be able to earn enough money to buy all the food that they need does not consider the relationships and social structures of inequality that affect their lives.

Household Foodwork, an Essential Service

The right to food itself is critical for, but not the same as, the right to eat. Indeed, a package of rice or dried beans is not immediately consumable. What often gets lost in thinking about food access is the essential labour required to literally put food on the table. Food itself generally needs to be transformed through the use of physical resources (e.g., tools and energy sources for cooking) and the labour of acquiring, preparing, and serving the food in ways that meet eaters’ needs. Since human survival and well-being utterly depend on food, they utterly depend on the foodwork, within or outside the home, that makes food edible. Given people’s varying skills, capacities, and circumstances, it is rare for any person to be completely self-reliant in producing, processing, and preparing all the food that they require.

The start of the COVID pandemic shone a harsh light on the essentiality of household foodwork as expectations for it grew. Household foodworkers, primarily women, faced increased challenges as children required more meals at home, elementary and high school students could no longer access food from programs at school, some supermarket shelves emptied, and all public places, including those selling or donating food, were seen as sites of potential COVID exposure. Foodwork extended to disinfecting groceries, waiting in lines outside grocery stores, and generally reconciling household food needs with the pandemic-related risks and regulations pertaining to acquiring food. This work has been crucial for ensuring that people remain alive and healthy.

Household Foodworkers: Some plates are fuller than others

Despite how necessary it is, household foodwork cannot be separated from a political context in which power, money, food access, and effort are unequally distributed. Social structures of inequity, such as sexism, racism, and poverty, combine so that both the efforts required and the resources available for household foodwork are unevenly assigned. For example, even with significant increases in women working in paid employment[8] and men doing domestic work,[9] women continue to perform the bulk of foodwork.[10] However, except for some mothers’ ability to breastfeed, actual foodwork abilities are not limited to just women. This discrepancy means that mothers in particular, especially those with low incomes, face difficult choices between providing in-person care for their children and participating in paid employment to afford to feed them.

Racialized poverty and racialized food system labour interfere with food access and the opportunity for adults to be physically present and able to feed their own families. Food is persistently kept out of reach for the 28.2% of Indigenous and 28.9% of Black individuals who live in food insecure households.[11] Racialized workers disproportionately fill low-wage, precarious jobs in food retail while their employers post huge profits.[12] Furthermore, a long history continues in which migrant women of colour support their own families in their home countries by providing household foodwork and other caring labour in the homes of North American, mostly White, families.[13] Similarly, (primarily) male migrant agricultural labourers work in underpaid, insecure, and unsafe conditions to feed Canadians, in order to financially support the vital needs of their own families back in their home countries. In addition to these barriers to having the ‘privilege’ to do household foodwork for one’s own family, foodwork can also be impeded by difficulty in having access to culturally specific foods, stigma around the consumption of certain foods, and a lack of understanding by health and teaching professionals regarding the appropriateness of particular foods and food practices.

Foodwork as Heartwork

Sociologist Mignon Duffy states “We should be able to value relationship without reducing care to the warm and fuzzy.”[14] The ways in which household foodwork’s concrete physical necessity and its ‘fuzzier’ emotional and social dimensions intertwine make it hard to perceive its value. Connecting with loved ones by understanding and responding to their food needs places household foodwork activities within social relationships. Here, these activities transform into caring labour, a medium for expressing love, affection, creativity, playfulness, and commitment—but also a source of judgement, guilt, shame, frustration, and anxiety. The breadth of these emotions relates in part to the dual meaning of “caring.” The word can simultaneously act as both a verb and an adjective, both an action and a personality characteristic—so that the work of caring for fuses with the emotion of caring about and the state of being a caring person.[15] The result is that work that comes from the heart (or that is expected to) is easily exploitable and not fully regarded as work. It holds a contradictory position where it is necessary and demanded, but not fully seen or valued. This invisibilization of care operates so effectively that it blocks questions about whether those responsible for foodwork should even be supported in doing so—leaving those with limited resources having to fend for themselves.

What happens when resources are not adequate to meet needs

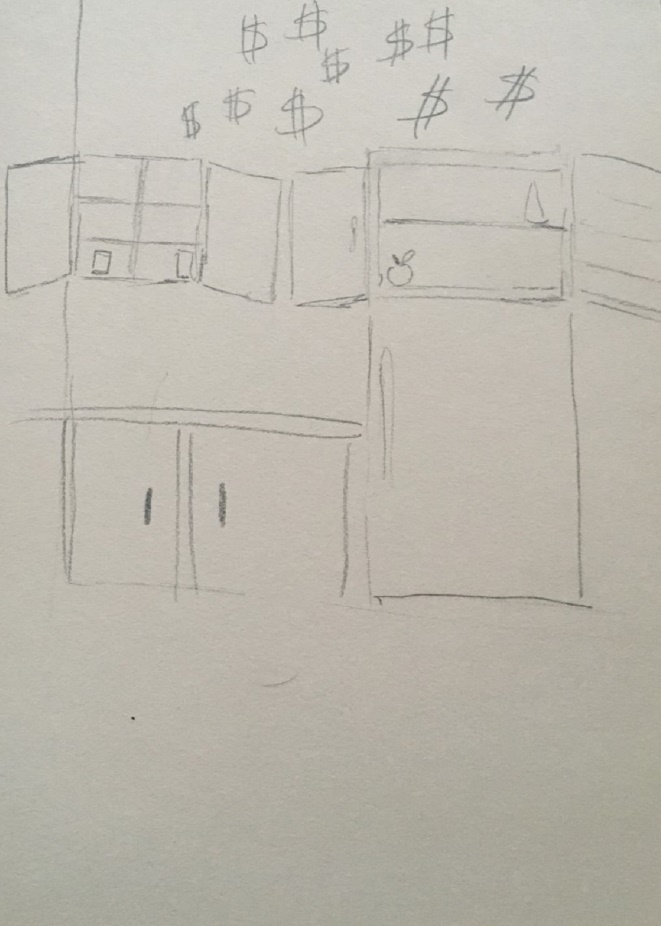

Because food is treated as a commodity, people without sufficient money to pay for it must be resourceful in finding ways to access it. The low-income mother who drew the dollar signs and almost-empty cupboards and fridge in Figure 2 explained that money is the main reason that she cannot gain access to enough food for her family.[16] Insufficient incomes increase foodwork in many ways: walking long distances for groceries; determining how to make meals from food bank offerings; calculating how to stretch an inadequate budget; and helping children feel valued when ‘special’ foods are not affordable. A significant portion of the foodwork of marginalized women involves acting as “shock absorbers”[17] to bridge gaps between household food needs and available resources.

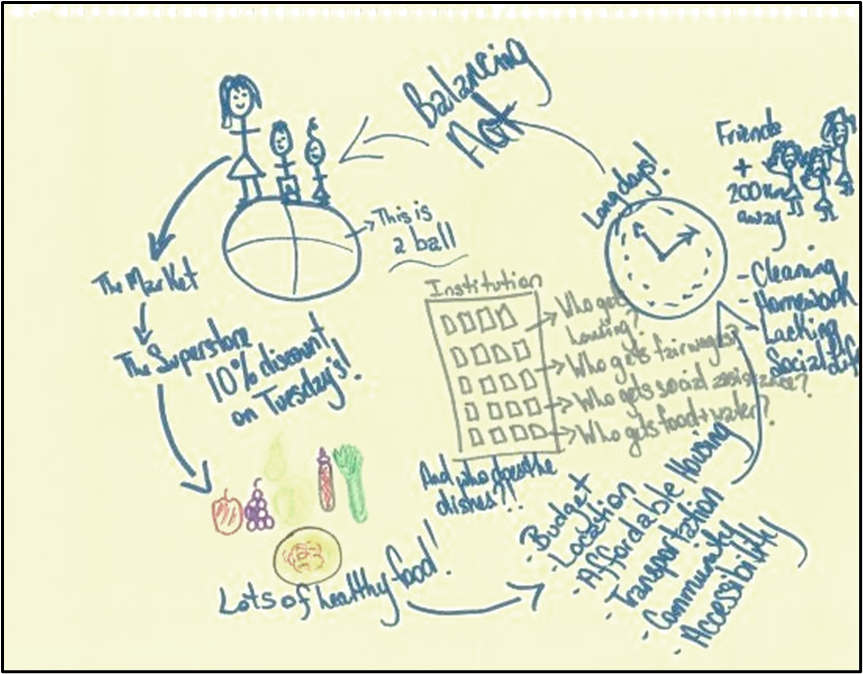

As an example, a low-income mother’s drawing in Figure 3 illustrates many of her experiences regarding food in her life.[18] With the ball, she shows the delicate act of balancing considerations around healthy food, affordability of food, other costs (like housing), social isolation, and time demands. At the same time, she recognizes that it is not entirely her responsibility to reconcile these issues and that policy makers (at the “institution”) play a role in allocating money for necessary resources.

When household resources are limited, women often assume added responsibility to make ends meet by using their own resourcefulness. This responsibilization is shown as they stretch food by using sales and coupons, using less expensive ingredients, growing or preserving their own food, and going without food themselves. Women also try to free up more funds for food through juggling other expenses, reducing medication consumption, and putting off expenditures like new clothes or haircuts. They participate in informal economic activities such as bartering, engaging in odd jobs, and selling personal items. This bridging between resources and need also occurs through risky, punishable, and demeaning behaviour, such as asking friends and family for help, applying to social assistance programs, accessing food banks, engaging in adult entertainment or sex work, and participating in dishonest or criminal activity.[19] These kinds of attempts to bridge household food needs with the resources for them clearly demonstrate the cost to women that results from ‘having to figure it out.’ The sense that people are on their own in meeting their basic needs and those of their loved ones demonstrates a form of individualism.

Beyond the Individualizing of Household Foodwork: No eater is an island

Although household foodwork is necessary for human well-being and for all the activities we do in the world, the responsibilities and resources for this work are not distributed evenly. Women continue to take on the brunt of this labour, while many people who work within the industrial food system, especially women and people who are racialized, are prevented from directly or adequately feeding their own families. Food access is far from assured, even in rich countries. For example, despite Canada’s repeated commitments, food insecurity is a growing crisis, especially affecting those who are Indigenous, Black, and/or parenting children. For some, making foodwork tenable comes at a distinct cost, which is often paid by women. Throughout, we see how care is invisibilized and how responsibility rests heavily on individuals to “make it work.” Moving forward towards a fairer food system that values what is essential means addressing an over-emphasis on the individual.

Making the normal abnormal

An important first step in imagining alternatives for ensuring that people can eat what they need is to rethink or de-normalize assumptions. It is important to question, for example: Why are food prices and incomes so incompatible that they make food inaccessible for many people? Are the poverty and food insecurity of single mothers, Indigenous people, and racialized people unchangeable? What is the role of the state, if not to ensure its people’s well-being? Moving towards more equitable futures requires questioning current realities.

Where is interdependence working?

The dominant food system sees people as detached from one another and privileges the choices of individuals—instead of supporting projects that redefine food as being for the collective use and enjoyment of all. Beyond questioning the status quo, it is important to look for existing examples of better alternatives and to discover those places where people work collectively and interdependently. Food co-ops, community kitchens, neighbourhood food exchanges, and community gardens are some of those places.[20]

No eater is an island

Food systems are utterly dependent on human foodworkers and non-human actors (e.g. animals, water, trees). To ensure that everyone can eat sufficiently requires questioning who really depends on whom, and embracing the reciprocity and interdependence of all actors (human and non-human) in the food system. It means thinking about the people, animals, waters, and plants that all played a role in food reaching our plates.

Working on our relationship with the state

The state has an important role to play in ensuring that people can eat. Policies around income, agriculture, land planning, and even housing and childcare influence whether people can access the food that they need. Within the food system, it is important to see ourselves not just as consumers. We also need to see ourselves as citizens with both the right to food and the responsibility to hold the state accountable for ensuring it. This can mean informing ourselves, voting, contacting elected officials, and educating others about the policies that are necessary.

Discussion questions

- What are some ways in which food access and household foodwork are related?

- Does it matter who does the dishes? Why or why not?

- What are some examples of exploiting, devaluing, externalizing, or invisibilizing the resources and labour that support the global industrial food system?

- What kinds of policies, programs, initiatives, or practices might support household foodwork?

Exercise

Think about a time when you had to be responsible for your own meal(s). How does that compare with times when you were part of a collective food experience? What was or was not possible in each situation?

With a partner, share your experiences and discuss similarities and differences. Identify some of the key factors that shaped what was or was not possible in each situation.

Additional Resources

Martin, M.A. (2018). Moms feeding families on low incomes in Peterborough and the support of community-based food initiatives.

Ontario Basic Income Network. (2021). The Case for Basic Income Series

Two cases here are particularly relevant to this text: The Case for Basic Income for Food Security ; and The Case for Basic Income for Women.

Tarasuk, V. & Mitchell, A. (2020). Household food insecurity in Canada, 2017-18. Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

Waring, M. (1999). Counting for nothing: What men value and what women are worth (2nd Ed.). Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

References

Arat-Koç, S. 2006. “Whose Social Reproduction? Transnational Motherhood and Challenges to Feminist Political Economy”. In Social Reproduction, Edited by Meg Luxton and Kate Bezanson, 75–92. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press.

Bakan, A. and D. Stasiulis . 2005. Negotiating Citizenship: Migrant Women in Canada and the Global System . Toronto: University of Toronto Press .

Beagan, B., G.E. Chapman, A. D’Sylva,and B.R. Bassett. 2008. “‘It’s Just Easier for Me to Do It’: Rationalizing the Family Division of Foodwork.” Sociology42 (4): 653–671.

Block, S.B. and S. Dhunna. 2020. “COVID-19: It’s Time to Protect Frontline Workers.” Behind the Numbers, March 31, 2020.

DeVault, M.L. 1991. Feeding the Family:The Social Organization of Caring as Gendered Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Duffy, M. 2011. Making Care Count: A Century of Gender, Race, and Paid Care Work. Piscataway, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 2021. “The Right to Food around the Globe.”

Gibson-Graham, J.K. 2006. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Houle, P., M. Turcotte and M. Wendt. 2017. “Changes in Parents’ Participation in Domestic Tasks and Care for Children from 1986 to 2015,” Statistics Canada.

Jaffe, J. and M. Gertler. 2006. “Victual Vicissitudes: Consumer Deskilling and the (Gendered) Transformation of Food Systems.” Agriculture and Human Values, 23: 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-005-6098-1

Martin, M.A. 2018. “‘At Least I Can Feel Like I’ve Done My Job As a Mom’: Mothers on Low Incomes, Household Food Work, and Community Food Initiatives,” PhD dissertation. Trent University.

Martin, M.A. 2018. “Moms Feeding Families on Low Incomes in Peterborough and the Support of Community-Based Food Initiatives.”

Martin, M.A., M. Classens, and A. Agyemang. 2021. “From Crisis to Continuity: A Community Response to Local Food Systems Challenges In, and Beyond the Days of COVID-19,” Trent University, 2021.

Moon, J. 2018. “Supermarkets Are Making Huge Profits at a Time When Food Prices Are Rising and Canadians Are Suffering, Advocates Say,” St. Catharines Standard, November 18, 2020.

Moyser, M. and A. Burlok. 2018. “Time Use: Total Work Burden, Unpaid Work, and Leisure.” Statistics Canada.

Neysmith, S., M. Reitsma-Street, S.B. Collins, and E. Porter. 2012. Beyond Caring Labour to Provisioning Work. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Neysmith, S., M. Reitsma-Street, S. Baker Collins, and E. Porter. 2004. “Provisioning: Thinking About all of Women’s Work.” Canadian Women’s Studies 23 (3/4): 192–8.

Pelletier, R. & M. Patterson. 2019. “The Gender Wage Gap in Canada: 1998 to 2018.” Statistics Canada.

Rideout, K., G. Riches, A. Ostry, D. Buckingham, and R. MacRae. 2007. “Bringing Home the Right to Food in Canada: Challenges and Possibilities for Achieving Food Security.” Public Health Nutrition10 (6): 566–573. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980007246622567

Silva, C.. 2020. “Food Insecurity In The U.S. By The Numbers.” September 27, 2020,

Statistics Canada. 2020. “Family Matters: Sharing Housework among Couples in Canada: Who Does What?” February 19, 2020.

Tarasuk, V. and A. Mitchell. 2020. “Household food insecurity in Canada 2017-18.” Toronto: Research to identify policy options to reduce food insecurity (PROOF).

Waring, M. 1999. Counting for nothing: What men value and what women are worth (2nd Ed.). Toronto and Buffalo: University of Toronto Press.

- See Waring 1999. ↵

- Jaffe & Gertler 2006. ↵

- Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020. ↵

- FAO 2021. ↵

- This included participation by all provinces and territories but excluded some groups like people living on First Nations reserves, in prisons or in care facilities. Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020; Silva 2020. ↵

- Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020. ↵

- Pelletier & Patterson 2019; Moyser & Burlok/Statistics Canada 2018. ↵

- From 1976 to 2015, the employment rate for women (25 to 54 years) rose from 48.7% to 77.5%. Houle et al. 2017 ↵

- Moyser & Burlok/Statistics Canada 2018. ↵

- Beagan et al. 2008; A study conducted by Statistics Canada among parents found that fathers preparing meals rose from 29% in 1986 to 59% in 2015 and that mothers preparing meals remained high but dropped somewhat during this time from 86% to 81%. Houle et al. 2017; A study of opposite-sex couples living in the same household found that meal preparation was done more often by women (56%), but that dishwashing was done equally by men and women. Statistics Canada 2020; These studies do not consider the full complement of foodwork involved in feeding a household. ↵

- Tarasuk & Mitchell 2020. ↵

- Block & Dhunna 2020; Moon 2020. ↵

- Arat-Koç 2006. ↵

- Duffy 2011, 40. ↵

- See DeVault 1991; Neysmith et al. 2004. ↵

- Martin et al. 2021. ↵

- Bakan & Stasiulis 2005, 24. ↵

- Martin 2018. ↵

- Martin 2018, 7-9; Neysmith et al. 2012. ↵

- See J.K. Gibson-Graham 2006. ↵