12.3: Indigenous Tourism in Canada

- Page ID

- 9373

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Evolution of Indigenous Tourism in Canada

While there has always been some demand among visitors to Canada to learn more about Indigenous heritage, driven by the strong interest of Europeans in particular, until recently there has been no concerted effort to focus on defining and strengthening Indigenous cultural tourism. However, over the last 25 years or so, steps have been taken to support authentic Indigenous cultural products and experiences and to counter decades of appropriation of Indigenous symbols and arts and crafts by non-Indigenous Canadians and others elsewhere in the world.

Indigenous exhibits and displays were developed for tourism attractions and museums by well-meaning non-Indigenous people who did not consult with local communities. Souvenir shops were often filled with inexpensive overseas-made replicas of authentic Indigenous arts and crafts, and some still are. To this day, we see the Canadian Prairie Indigenous headdress being used as a way of (mis)representing First Nations across Canada. As an example of how things have changed, in August 2020 the Yukon First Nations Arts Brand was created to promote and celebrate ‘all forms of art made by Indigenous artists living in Yukon Territory’. Developed and controlled by the Yukon First Nations Culture and Tourism Association (YFNCT), the brand program will showcase arts and crafts made by Yukon First Nations people. For more information, go to the Yukon First Nations arts website.

As the number of Indigenous tourism businesses started to increase in the 1980s and 1990s, the federal government initiated discussions on Indigenous tourism. The outcome was the formation of national organizations that provided a coordinated industry voice for operators: Aboriginal Tourism Team Canada (ATTC), Aboriginal Tourism Canada, and Aboriginal Tourism Marketing Circle (ATMC), and others. These groups started the trend of defining Indigenous cultural tourism standards and promoting the establishment of regional, provincial, and territorial organizations to develop and market more successful businesses. Today, these functions are performed by the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC).

Spotlight On: Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada

Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC) is a consortium of over 20 Indigenous tourism industry organizations and government representatives from across Canada. It was formed to create a unified voice and was formalized in 2014 as the Aboriginal Tourism Association of Canada (ATAC) and built from the ATMC established in 2009. ITAC continues to evolve to support marketing, product development and training standards, and other initiatives. For more information, visit the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada.

Indigenous Tourism in Canada Today

Thanks to the growing visitor demand for authentic cultural experiences and the strong leadership of ITAC, Indigenous tourism in Canada continues to mature and has proven to be a major economic and cultural driver for Indigenous communities across Canada. In early 2020 there were a reported 1,900 Indigenous tourism businesses employing 40,000 workers and generating $1.9 billion of direct GDP contributions to the Canadian economy (ITAC, 2020).

Take a Closer Look: Canada’s Indigenous Tourism Sector: Insights and Economic Impacts

This 2019 report through the Conference Board of Canada was “commissioned by the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada (ITAC) to profile and assess the economic impact of Canada’s Indigenous tourism sector. The report delivers an updated direct economic footprint of the Indigenous tourism sector in 2017, including GDP, employment, and business growth. In addition, the report provides strategic insights from a 2018 survey of Indigenous businesses that participate in the Indigenous tourism sector in Canada.”

To review the report, visit Canada’s Indigenous Tourism Sector: Insights and Economic Impacts [PDF].

In 2019 the Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada published a comprehensive set of guidelines developed in consultation with industry members, Elders and community that endorsed the following definitions of Indigenous Tourism with the recognition that each nation, culture or community can choose to adopt or adapt these definitions to best suit their needs (ITAC, 2019, p.8):

Indigenous Tourism is defined as a tourism business majority owned, operated and/or controlled by First Nations, Métis or Inuit peoples which demonstrates a connection and responsibility to the local Indigenous community and traditional territory where the operation is based.

Indigenous Cultural Tourism not only meets the Indigenous tourism criteria (above) but in addition a significant portion of the experience incorporates a distinct Indigenous culture in a manner that is appropriate, respectful and true. Authenticity lies in the active involvement of Indigenous people in the development and delivery of the experience.

With these definitions, ITAC also provides the vital clarification that, “There are tourism businesses which are neither majority owned nor operated by Indigenous People who offer ‘Indigenous tourism experiences’. Authentic Indigenous Cultural Tourism is by Indigenous peoples, not about Indigenous peoples” (italics added; ITAC, 2019).

Take a Closer Look: National Guidelines – Developing Authentic Indigenous Experiences in Canada

This 2019 document from ITAC was designed as a self-assessment and reference tool and created in consultation with Elders, industry and the community to give guidance and direction for all involved within the Canadian Indigenous tourism industry. The Indigenous Tourism Association of Canada continues to provide guidance for Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, business leaders and other Indigenous tourism stakeholders on standards.

To view the report, visit National Guidelines: Developing Authentic Indigenous Experiences in Canada [PDF].

Strengthening Indigenous Tourism in Canada

Tourism is of significant interest to growing numbers of Indigenous communities in Canada. If developed in a thoughtful and sensitive manner, it can have potential positive economic, cultural, and social impacts. Many communities have undertaken tourism development activities to support cultural revival, intercultural awareness, and economic growth. This growth brings jobs and career opportunities for Indigenous people at all skill levels.

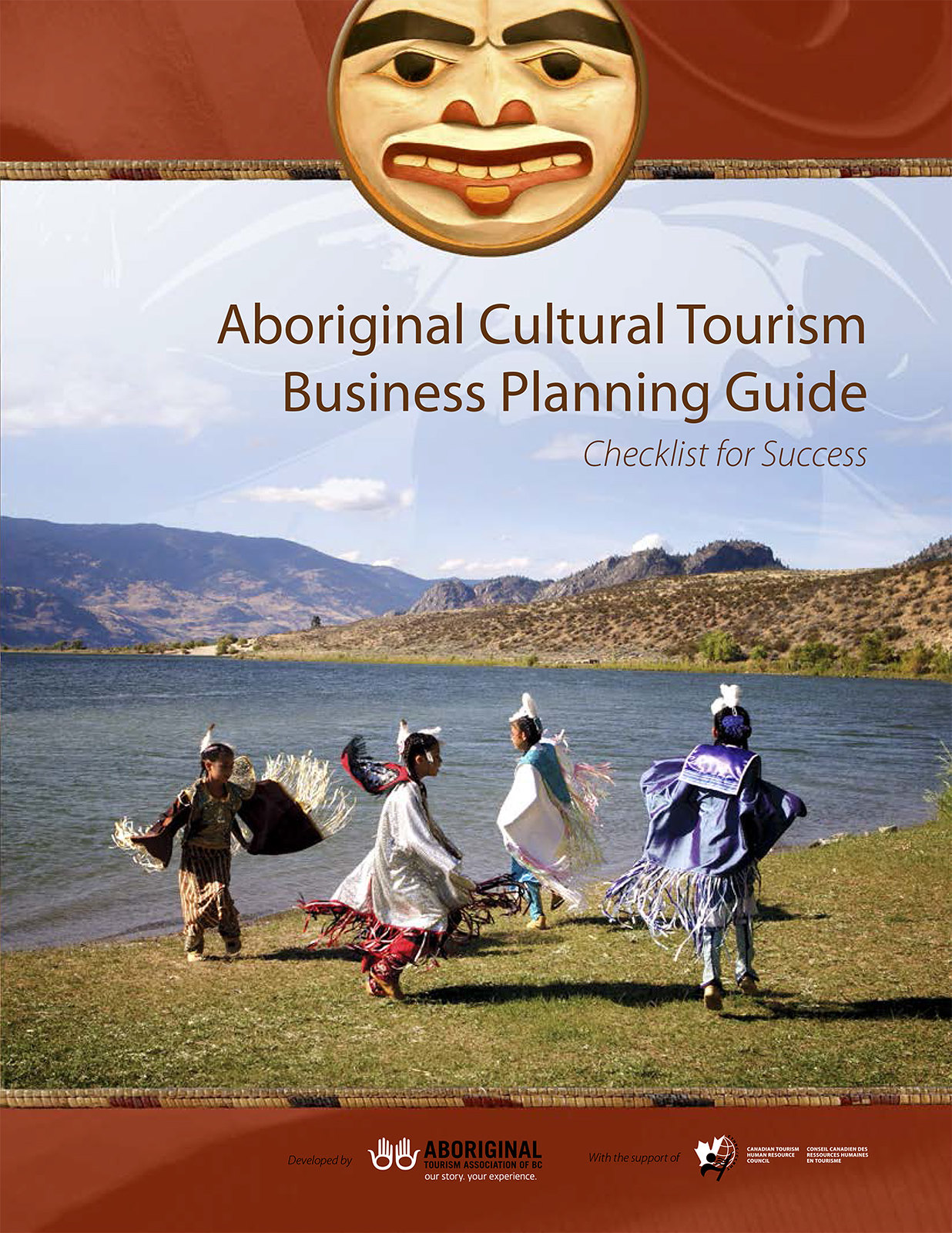

The Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide suggested the following as the foundational building blocks necessary to run a successful and authentic Indigenous tourism business:

- Understand the industry, learn about cultural tourists, and develop products carefully

- Ensure experiences are culturally authentic

- Involve the community’s ‘culture keepers’ and Elders

- Practice environmental sustainability

- Prepare an Indigenous cultural tourism business plan

- Meet visitor expectations through staff training and excellent hospitality, provided from a cultural perspective

- Ensure an effective web and social media presence

- Build personal support networks

The guide also highlights the importance of place to the Indigenous tourism experience. It suggests that guests leave an authentic tourism experience with a memorable collection of feelings, memories, and images that all contribute to a unique sense of place and help guests understand the culture being shared (Kanahele, 1991). In order to highlight this sense of place, operators are encouraged to reflect on and impart aspects of their culture with the following elements of their business (Indigenous Tourism BC & CTHRC, 2013):

- Decor such as signage, displays, art, photography

- Company name

- Branding elements such as logo and website design

- Employee uniforms or dress code

- Food and beverage

- Traditional stories shared with guests

- Key words and expressions from the Indigenous host language shared in guest interactions

These touch points create a richer, and more authentic, experience for the visitor.

As an Elder once stated, Indigenous tourism businesses showcase “culture, heritage and traditions,” and “because these belong to the entire community, the community should have some input” (Aboriginal Tourism BC & CTHRC, 2013, p. 19). For this reason, the guide suggests operators consider the extent to which:

- Community members understand the project or business as it is being proposed

- Keepers of the culture are engaged in the development of the idea

- The business or experience reflects community values

Take a Closer Look: Indigenous Cultural Tourism Checklist (Canada) and Maori Tourism Checklist (New Zealand)

Review the Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide at Aboriginal Cultural Tourism Business Planning Guide [PDF].

The Maori tourism organization in New Zealand has developed a similar guide for Indigenous tourism development. Visit the New Zealand Maori Tourism Road Map.

By following these guidelines, Indigenous tourism businesses can honour the principles outlined in the Larrakia Declaration and other similar documents.

Indigenous Tourism’s Interconnection with Land Stewardship

The intersection of conservation, tourism and Indigenous cultural resurgence is receiving growing attention in the Canadian context, particularly within British Columbia. Indigenous peoples’ connection to the land is well documented and is widely understood as central to Indigenous cultural identity and future prosperity (Brown & Brown, 2009). As explained earlier in this text, the tourism industry is dependent upon the natural and cultural environment, yet tourism can be a direct threat to the health and quality of these essential tourism destination components. Indigenous tourism development is even more sensitive to risks associated with mismanagement given the relational interdependence of Indigenous culture and identity to the places and types of experiences that are increasingly sought after by visitors.

Take a Closer Look: National Indigenous Guardians Network in Canada

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative is a key supporter of a federally funded, Indigenous-led National Indigenous Guardians Network in Canada that supports development and employment of guardians across the country. Indigenous-led Guardian programs play a vital role in monitoring ecological changes and protecting sensitive cultural and environmental areas from the pressures related to Indigenous tourism development.

For more information, visit this web page on the Indigenous Guardians Program on the Indigenous Leadership Initiative website.

Additionally, review this web page on the Indigenous Guardians Pilot Program on the Government of Canada website.

There are a number of innovative responses to ecological threats to Indigenous lands that have emerged and evolved in recent years such as; co-management agreements of protected areas between public agencies and Indigenous people; the designation of new protected areas, best illustrated by the 1984 Meares Island Tribal Park declaration made by the Tla-o-qui-aht and Ahousat First Nations on the West Coast of Vancouver Island (British Columbia); and the establishment of Indigenous-led Guardian initiatives, such as the Coastal Guardian Watchmen program.

Take a Closer Look: Coastal Guardian Watchmen

The Coastal Guardian Watchmen program, active along the North and Central Coast, and Haida Gwaii region of British Columbia, illustrates the invaluable knowledge that is held within Indigenous communities and the role Indigenous people continue to play in protecting the cultural and natural resources of specific territories.

For more information, visit this web page on Coastal Guardian Watchmen Support on the Coastal First Nations: Great Bear Initiative website.

Examples of Canadian Indigenous Tourism Development

Over the past decades, hundreds of Indigenous-focused tourism experiences have developed in Canada. Examples include:

- The Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump interpretive centre in Alberta

- Northern lights viewing with Indigenous hosts at Aurora Village in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories

- Essipit whale watching with the Innu in Quebec

- Driving the Great Spirit Circle Trail of Indigenous experiences on Manitoulin Island in Ontario

- Cultural activities and wilderness adventures during summer and winter in the traditional territory of the Champagne & Ashihik First Nation, Yukon

Take a Closer Look: Indigenous Tourism Canada’s consumer website

Get curious and explore the many Indigenous tourism and cultural tourism businesses and experiences throughout Canada, including those close to where you live or places you’re otherwise familiar with. The interactive map on the ITAC website provides a great way to dive into this!

For an in-depth exploration of a Canadian Indigenous tourism destination, see the case study at the end of this chapter on the Trails of 1885 project. This and other initiatives have been successful across the country, including some in British Columbia, which has emerged as a premier destination for Indigenous tourism experiences.