5: Putting Evidence-Based Instructional Strategies to Work

- Page ID

- 45448

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Teach with evidence, not just enthusiasm.

At a technical college or in any classroom, using evidence-based instructional strategies helps ensure that all students can understand and engage with course material effectively. Two key approaches are Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) and Universal Design for Learning (UDL). TILT focuses on clearly communicating the purpose, tasks, and grading criteria of assignments, which helps students better understand what is expected of them and why it matters. UDL encourages instructors to offer multiple ways for students to access content, demonstrate their knowledge, and stay motivated, allowing for greater flexibility in the learning process. By applying these strategies, instructors can create more structured and supportive learning environments that improve student performance and persistence.

In this section, we will take a closer look at both TILT and UDL, exploring how these evidence-based strategies can strengthen teaching and improve student outcomes in technical college settings. By understanding the core principles of each approach, faculty can begin to identify practical ways to integrate them into their course design and instruction. The goal is to support more effective teaching and learning by making assignments clearer, increasing student engagement, and offering flexible pathways to success. Faculty are encouraged to reflect on their current practices and consider how TILT and UDL can be applied across all courses to enhance the overall learning experience.

Be Transparent

TILT: Transparency in Teaching and Learning

Transparency in teaching means going beyond delivering content; it involves explaining the why and how behind course design and assignments. While instructors often put significant thought into how each activity and assignment can shape students’ learning, they rarely make these intentions explicit to students. Transparency asks instructors to openly discuss not just what students are learning but how and why the learning process is structured as it is.

This approach to teaching is especially important for achieving equity in the classroom. Many students, particularly first-generation, low-income, and underrepresented students, may not automatically understand the reasoning behind academic assignments, the optimal ways to tackle them, or the benefits for their learning. These students can spend valuable time trying to decipher the purpose and expectations of an assignment rather than diving straight into the learning itself. By making clear the purpose, specific tasks, and assessment criteria before students start working, instructors provide all students a fairer chance to succeed. Without this clarity, the gap between students with prior knowledge of academic structures and those without can widen, perpetuating the advantages for those more familiar with the “unwritten rules” of academic work.

Some instructors worry that this level of transparency risks simplifying or “dumbing down” the course. In fact, the opposite is true: when students aren’t bogged down by trial and error, trying to figure out why an assignment matters or how to approach it, they can focus directly on the essential skills and content of the discipline. This allows students to engage deeply with complex concepts and apply them effectively, ultimately leading to higher-quality work.

Occasionally, a “gatekeeper” mindset suggests that if a student can’t intuitively grasp the unstated goals and criteria of an assignment, they aren’t suited for the field. But in practice, supporting more diverse ways of thinking benefits not only students but also the discipline. Many academic breakthroughs arise from people who approach problems differently, bringing unique perspectives or interdisciplinary ideas. Transparency in teaching can ensure that more of these “outlier” thinkers—those who see things from a fresh angle—advance to higher levels, contributing valuable insights and fostering innovative research in their fields.

Transparency in teaching and learning can be practically integrated through a variety of strategies that make the expectations and rationale behind assignments and course activities clear to students. Here are some ways transparency can look in practice:

Purpose-Task-Criteria (PTC) Framework:

- Purpose: Start each assignment or activity by explicitly explaining its purpose. For instance, “This assignment will help you develop skills in critical reading and synthesis, which are essential for crafting well-supported arguments in your field.”

- Task: Describe the specific steps students should take. Avoid general instructions like “analyze the text” and instead clarify steps like “Identify and summarize the main arguments in each article before comparing their approaches.”

- Criteria: Share detailed criteria for success, ideally with a rubric or list of specific goals. For example, “A strong paper will clearly explain the main arguments, offer evidence for each point, and consider alternative interpretations.”

Class Activity Rationale:

- Before an activity, explain its purpose and relevance to course goals. For example, “We’re doing this group discussion to practice articulating diverse perspectives, which will help us in analyzing case studies later in the course.”

- After the activity, provide a brief reflection on how the activity ties into larger course concepts and objectives. This helps students connect the immediate task to their broader learning journey.

Assignment Guides and Checklists:

- Create guides for major assignments that outline common pitfalls, best practices, and examples. For example, “An effective research paper in this field typically includes a clear thesis, peer-reviewed sources, and evidence-backed arguments.”

- Provide checklists that students can use to self-assess before submitting. This empowers students to monitor their progress and ensure they meet all assignment criteria independently.

Guided Reflection Prompts:

- Incorporate structured reflection prompts to encourage students to think about how they are learning, not just what they are learning. For instance, after a major assignment, you could ask, “What strategies did you use to approach this assignment? How did those strategies help or hinder your understanding of the topic?”

- Use these reflections as formative feedback to help students identify effective learning strategies, recognize areas for growth, and increase self-awareness.

Real-World Connections:

- Draw connections between assignments and real-world applications, which can be particularly motivating for students. For instance, “Learning how to analyze data trends in this assignment mirrors the kind of work you might do in market research, policy analysis, or environmental science roles.”

- Encourage students to think about how specific skills developed in the course may be useful in their future careers, which helps contextualize their learning.

Collaborative Rubric Development:

- Engage students in co-creating rubrics or criteria for specific projects. This increases investment and helps clarify expectations. For example, ask students what they think an excellent project would include, then work together to refine a rubric based on these ideas.

- Review the rubric together before students begin working, discussing each criterion to ensure students understand what’s expected.

Mid-Semester Check-ins:

- Schedule a “transparency check-in” where students can ask questions about course activities, assignments, and grading criteria. This open dialogue helps address any lingering confusion and gives students insight into the instructor’s goals and teaching approach.

- Encourage feedback on assignments or activities that were particularly helpful or challenging, and adjust future assignments to better meet student needs.

Sharing the “Why” Behind Grading Policies:

- Explain the reasoning behind grading policies, such as why certain assignments are weighted more heavily, why late policies exist, and how each element reflects the learning goals. This can reduce student stress and build trust, as they better understand that policies are designed to support their learning, not just assess it.

- For example, explain, “Your project is weighted more because it integrates skills from the entire semester and is meant to represent a culminating learning experience.”

These practices help create a learning environment where students feel informed, valued, and engaged in their own learning process. By clearly communicating the rationale behind instructional choices, instructors can promote a deeper level of student commitment and enhance the inclusivity of their teaching.

Visit these resources for more information, templates, handouts, and other freely available materials.

- TILT Website [www.tilthighered.com]

- TILT Transparent Methods [www.tilthighered.com/transparent-methods]

Universal Design for Learning (UDL)

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) offers a framework for designing curriculum that provides all students—regardless of their backgrounds, abilities, or needs—with equitable opportunities to learn. Instead of a rigid, one-size-fits-all approach, UDL emphasizes flexibility and customization in instructional goals, methods, materials, and assessments, making learning accessible for everyone.

A Foundation in Variability

UDL is grounded in the understanding that learner variability is not an exception but a predictable part of the educational landscape. This approach acknowledges the full spectrum of diversity in how students engage with, process, and demonstrate their learning. Historically, learners at the “margins” were treated as exceptions, requiring accommodations or special strategies. UDL reframes this perspective, recognizing that designing for variability from the outset benefits all learners.

The Three-Network Model

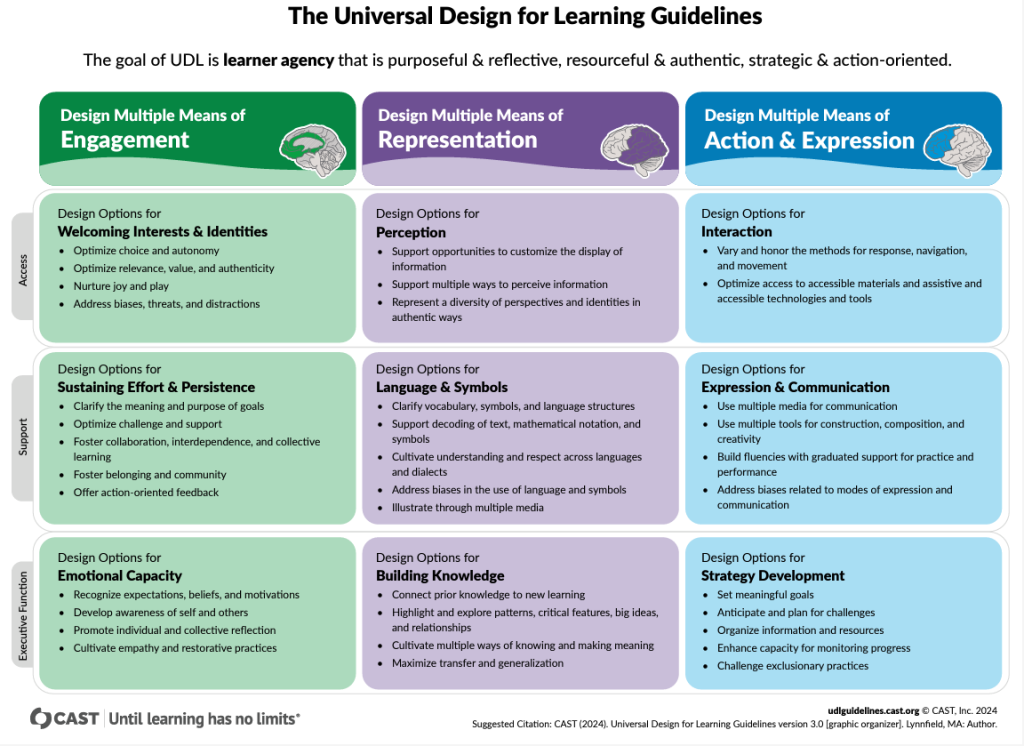

The UDL framework is based on a three-network model of learning, which considers the brain’s affective (engagement), recognition (representation), and strategic (action and expression) networks. These principles provide a foundation for designing learning environments that are inclusive and adaptable.

- Engagement: Offering multiple ways to inspire interest and sustain effort.

- Representation: Providing diverse formats for presenting information to ensure accessibility.

- Action and Expression: Offering varied methods for learners to demonstrate their understanding.

Guidelines for Application

The UDL Guidelines, developed from an extensive body of research, serve as benchmarks for minimizing barriers in curriculum design. Rather than a fixed checklist or formula, UDL provides principles that are flexible and contextual. These guidelines encourage educators to consider students’ developmental stages, cultural contexts, and their own teaching preferences, creating environments that are responsive and dynamic.

UDL as a Translational Framework

UDL acts as a bridge between research and practice. It is not a set of prescriptive tools but a flexible framework for innovation. Educators are encouraged to use UDL principles to design instructional strategies and select resources that fit their specific contexts. For example:

- Instructors can use digital tools to offer scaffolds and support that adapt to individual needs.

- Low-tech solutions like graphic organizers or tactile materials can be equally effective in addressing learner variability.

The Role of Students

A key aspect of UDL is involving students as active participants in their learning journey. Empowering students to become “experts” in their own learning means fostering self-awareness, persistence, and the ability to articulate their preferences and needs. This collaboration helps create a classroom culture where learning environments are co-designed to enhance access and engagement.

Technology and UDL

While digital technologies can amplify the application of UDL by enabling real-time customization and scaffolded supports, they are not the only solution. Effective UDL implementation blends high-tech and low-tech strategies, leveraging tools and methods that fit the needs of both the learners and the learning context.

Transforming Learning

At its core, UDL is about flexibility—rethinking traditional systems of teaching and learning to prioritize accessibility and inclusion. By designing with variability in mind, educators can create environments where all students thrive, moving beyond accommodation toward a truly inclusive educational experience.

UDL Guidelines 3.0: Expanding Access and Equity

The UDL Guidelines, first introduced in 2008, have been a foundational resource for designing inclusive and accessible learning environments. However, the dynamic nature of education and the evolving understanding of equity and access demand continuous growth. The release of UDL Guidelines 3.0 in July 2024 reflects the culmination of years of research, feedback, and collaborative input from scholars and practitioners around the globe.

This latest iteration explicitly addresses barriers rooted in bias and systemic exclusion, pushing the boundaries of previous versions to honor the complexity of learner variability and emphasize the importance of identity in the learning process. By integrating asset-based approaches, UDL 3.0 aligns itself more closely with broader movements in culturally responsive teaching and equity-focused pedagogy.

Key Expansions in UDL Guidelines 3.0

- Integrating Asset-Based Frameworks: UDL 3.0 engages in dialogue with other equity-centered and culturally sustaining pedagogies, emphasizing their complementary goals. This approach acknowledges and values the cultural and linguistic practices learners bring into the classroom, creating a richer, more inclusive framework for learning design.

- Recognizing Identity as Part of Variability: While previous UDL iterations focused on how learners engage, perceive, and express learning (the “why,” “what,” and “how”), the updated guidelines explicitly incorporate identity as the “who” of learning. By recognizing students’ intersecting identities—including race, culture, language, gender, and ability—UDL 3.0 encourages educators to design environments that affirm and celebrate this diversity.

- Addressing Bias at All Levels: The updated guidelines emphasize the need to confront individual, institutional, and systemic biases as fundamental barriers to learning. By doing so, UDL 3.0 aims to dismantle exclusionary practices that limit opportunities for certain groups and foster more equitable access to education.

- Valuing Interdependence and Collective Learning: Moving beyond the traditional emphasis on individual achievement, the new guidelines highlight the importance of collaboration and shared growth. This shift acknowledges the value of community and collective knowledge-building in fostering deeper, more meaningful learning experiences.

- Adopting Learner-Centered Language: A significant shift in UDL 3.0 is the use of language that reflects a learner-centered perspective. Verbs and phrases now apply interchangeably to educators and students, reinforcing the idea of shared responsibility and agency in designing and navigating learning experiences.

Enhanced Themes Within UDL Principles

The three core UDL principles—Engagement, Representation, and Action and Expression—are expanded in Guidelines 3.0 to deepen their connection to equity and inclusion:

Engagement:

- Affirming learners’ identities and interests

- Promoting belonging as a foundation for learning

- Emphasizing joy, play, and restorative practices in education

Representation:

- Showcasing authentic diversity in identities and narratives

- Valuing multiple cultural perspectives and ways of knowing

- Addressing historical erasure and bias in curricula

Action and Expression:

- Honoring diverse modes of communication, including those historically marginalized

- Challenging exclusionary practices to create equitable systems

- Providing space for creativity and self-expression that reflects individual and cultural authenticity

Connecting UDL 3.0 to Broader Access and Equity Efforts

The updates in UDL Guidelines 3.0 resonate strongly with themes of access and equity woven throughout this guide. By emphasizing the systemic and cultural dimensions of inclusion, UDL 3.0 offers educators a powerful lens through which to evaluate and refine their teaching practices. Its focus on flexibility, identity, and interdependence aligns with a shift from a deficit-based to an asset-based understanding of learner variability.

By incorporating UDL 3.0 principles, educators can design environments where all learners—especially those historically excluded or marginalized—can thrive. This framework invites us to re-imagine teaching and learning as a collaborative, dynamic, and deeply human process that values the richness of every learner’s identity.

- In what ways might clearly communicating learning goals alongside offering multiple ways to engage and express understanding help reduce student confusion and increase confidence?

- How might pairing clear, transparent assignment instructions with varied learning materials and assessment options support students in taking ownership of their learning?

- How can combining TILT’s focus on transparency with UDL’s flexible approaches reduce barriers and encourage all students to demonstrate their true abilities?

Sources and Attribution

Primary Sources

This section is informed by and adapted from the following sources:

- Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) Higher Ed Project. TILT Higher Ed Resources and Research. Available at: TILT Higher Ed Website (opens in new window)

- Project Information Literacy (2022). Smart Talk Interview: Transparency in Teaching and Learning. Available at: Project Information Literacy (opens in new window)

- CAST. Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Guidelines. Available at: UDL Guidelines (opens in new window)

- CAST. UDL on Campus: Universal Design for Learning in Higher Education. Available at: UDL on Campus (opens in new window)

Use of AI in Section Development

This section was developed using a combination of existing research, expert perspectives, and AI-assisted drafting. ChatGPT (OpenAI) was used to:

- Organize and refine key concepts from TILT research into a cohesive and accessible framework for instructors.

- Clarify practical applications of transparency strategies in teaching and learning.

- Ensure readability and engagement while preserving the core principles of evidence-based transparency practices.

While AI-assisted drafting provided a structured foundation, all final content was reviewed, revised, and contextualized to maintain accuracy, alignment with research, and practical applicability. This section remains grounded in scholarly and institutional best practices and respects Creative Commons licensing where applicable.

Media Attributions

- UDL 3.0