Lesson 2.2: Process HACCP for Recipes

- Page ID

- 11368

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Chapter Outline:

- Why HACCP?

- Retail foodservice operations that should implement HACCP

- Food safety hazards

- HACCP as a food safety management system

- HACCP principles for use in retail foodservice operations

- Process HACCP

Learning Objectives:

- Identify TCS (potentially hazardous) foods that require time and temperature control for safety.

- Use HACCP processes to identify critical control points and limits in the foodservice system

- Describe how to use process HACCP to incorporate critical control points and limits in recipes.

Key Terms:

- HACCP – Hazard Analysis Critical Control Points

- TCS foods (time temperature control for safety)

- Critical control points (CCPs)

- Critical limits

The Food Code clearly establishes that the implementation of HACCP at retail (foodservice operations) should be a voluntary effort by industry.

If, however, you plan on conducting certain specialized processes that carry a considerably high risk, you should consult your regulatory authority to see if you are required to have a HACCP plan. Examples of specialized processes covered in Chapter 3 of the Food Code include formulating a food so that it is not potentially hazardous or using performance standards to control food safety.

Federal performance standards define public food safety expectations for a product usually in terms of the number of disease-causing microorganisms that need to be destroyed through a process. For example, instead of cooking chicken to 165 ºF for 15 seconds as dictated in the Food Code, performance standards allow you to use a different combination of time and temperature as long as the same level of public safety is achieved. The use of performance standards allows you to use innovative approaches in producing safe products.

What are the retail and food service industries?

Unlike many food processing operations, the retail and food service industries are not easily defined by specific commodities or conditions. These establishments share the following characteristics:

- These industries have a wide range of employee resources, from highly trained executive chefs to entry level front line employees. Employees may have a broad range of education levels and communication skills. It may be difficult to conduct in-house training and maintain a trained staff because employees may speak different languages or there may be high employee turnover.

- Many are start-up businesses operating without the benefit of a large corporate support structure. Having a relatively low-profit margin means they may have less money to work with than other segments of the food industry.

- There is an almost endless number of production techniques, products, menu items, and ingredients used. Suppliers, ingredients, menu items, and specifications may change frequently.

What are food safety hazards?

Hazards are biological, physical, or chemical properties that may cause food to be unsafe for human consumption. The goal of a food safety management system is to control certain factors that lead to out-of-control hazards. Because many foods are agricultural products and have started their journey to your door as animals and plants raised in the environment, they may contain microscopic organisms. Some of these organisms are pathogens, which means that under the right conditions and in the right numbers, they can make someone who eats them sick. Raw animal foods such as meat, poultry, fish, shellfish, and eggs often carry bacteria, viruses, or parasites that can be harmful to humans. (These types of foods have been labels as TCS, time and temperature control for safety, foods.

The use of HACCP as a food safety management system

Since the 1960s, food safety professionals have recognized the importance of HACCP principles for controlling risk factors that directly contribute to foodborne illness. The principles of HACCP embody the concept of active managerial control by encouraging participation in a system that ensures foodborne illness risk factors are controlled.

The success of a HACCP program (or plan) is dependent upon both facilities and people. The facilities and equipment should be designed to facilitate safe food preparation and handling practices by employees. Furthermore, the FDA recommends that managers and employees be properly motivated and trained if a HACCP program is to successfully reduce the occurrence of foodborne illness risk factors. Instilling food workers and management commitment and dealing with problems like high employee turnover and communication barriers should be considered when designing a food safety management system based on HACCP principles.

Properly implemented, a food safety management system based on HACCP principles may offer you the following other advantages:

- Reduction in product loss

- Increase in product quality

- Better control of product inventory

- Consistency in product preparation

- Increase in profit

- Increase in employee awareness and participation in food safety

How can HACCP principles be used in retail and food service operations?

Within the retail and food service industries, the implementation of HACCP principles varies as much as the products produced. The resources available to help you identify and control risk factors common to your operation may also be limited. Like many other quality assurance programs, the principles of HACCP provide a common-sense approach to identifying and controlling risk factors. Consequently, many food safety management systems at the retail level incorporate some, if not all, of the principles of HACCP. While a complete HACCP system is ideal, many different types of food safety management systems may be implemented to control risk factors. It is also important to recognize that HACCP has no single correct application.

What are the seven HACCP principles?

1. Perform a Hazard Analysis. The first principle is about understanding the operation and determining what food safety hazards are likely to occur. The manager needs to understand how the people, equipment, methods, and foods all affect each other. The processes and procedures used to prepare the food are also considered. This usually involves defining the operational steps (receiving, storage, preparation, cooking, etc.) that occur as food enters and moves through the operation. Additionally, this step involves determining the control measures that can be used to eliminate, prevent, or reduce food safety hazards. Control measures include such activities as an implementation of employee health policies to restrict or exclude ill employees and proper handwashing.

2. Decide on the Critical Control Points (CCPs). Once the control measures in principle #1 are determined, it is necessary to identify which of the control measures are absolutely essential to ensuring safe food. An operational step where control can be applied and is essential for ensuring that a food safety hazard is eliminated, prevented or reduced to an acceptable level is a critical control point (CCP). It is important to know that not all steps are CCPs. Generally, there are only a few CCPs in each food preparation process because CCPs involve only those steps that are absolutely essential to food safety.

3. Determine the Critical Limits. Each CCP must have boundaries that define safety. Critical limits are the parameters that must be achieved to control a food safety hazard. For example, when cooking pork chops, the Food Code sets the critical limit at 145 ºF for 15 seconds. When critical limits are not met, the food may not be safe. Critical limits are measurable and observable.

4. Establish Procedures to Monitor CCPs. Once CCPs and critical limits have been determined, someone needs to keep track of the CCPs as the food flows through the operation. Monitoring involves making direct observations or measurements to see that the CCPs are kept under control by adhering to the established critical limits.

5. Establish Corrective Actions. While monitoring CCPs, occasionally the process or procedure will fail to meet the established critical limits. This step establishes a plan for what happens when a critical limit has not been met at a CCP. The operator decides what the actions will be, communicates those actions to the employees, and trains them in making the right decisions.

6. Establish Verification Procedures. This principle is about making sure that the system is scientifically-sound to effectively control the hazards. Designated individuals like the manager periodically make observations of employees’ monitoring activities, calibrate equipment and temperature measuring devices, review records/actions, and discuss procedures with the employees.

7. Establish a Record Keeping System. There are certain written records or kinds of documentation that are needed in order to verify that the system is working. These records will normally involve the HACCP plan itself and any monitoring, corrective action, or calibration records produced in the operation as a part of the HACCP system.

FDA endorses the voluntary implementation of food safety management systems in retail and food service establishments. Combined with good basic sanitation, a solid employee training program, and other prerequisite programs, HACCP can provide you and your employees a complete food safety management system. The goal in applying HACCP principles in retail and food service is to have you, the operator, take purposeful actions to ensure safe food. You and your regulatory authority have a common objective in mind – providing safe, quality food to consumers.

Managing food safety should be as fully integrated into your operation as those actions that you might take to open in the morning, ensure a profit, or manage cash flow. By putting in place an active, ongoing system, made up of actions intended to create the desired outcome, you can achieve your goal of improving food safety. The application of the HACCP principles provides one system that can help you accomplish that goal.

Check with your local regulatory agency

The FDA Food Code identifies TCS foods and temperatures necessary for keeping food safe. These include receiving and cold holding temperatures, minimum internal cooking temperatures for a variety of foods and cooking methods, hot holding and cooling temperatures. The federal food code is based on scientific evidence and recommended for adoption by states in the U.S., however exact temperatures can vary by states and health departments, so be sure to check the specific regulations in your area.

APPLYING HACCP PRINCIPLES TO RETAIL AND FOOD SERVICE

What is the process approach?

Since the early 1980s, retail and food service operators and regulators have been exploring the use of HACCP in restaurants, grocery stores, and other retail food establishments. Most of this exploration has centered on the question of how to stay true to the definitions of HACCP yet still make the principles useful to an industry that encompasses a very broad range of conditions. Through this exploration, HACCP principles have been slightly modified to apply to the varied operations found at retail.

When conducting the hazard analysis, food manufacturers usually use food commodities as an organizational tool and follow the flow of one product. This is a very useful approach for producers or processors since they are usually handling one product at a time. By contrast, in retail and

food service operations, foods of all types are worked together to produce the final product. This makes a different approach to the hazard analysis necessary. Conducting the hazard analysis by using the food preparation processes common to a specific operation is often more efficient and useful for retail and food service operators. This is called the “Process Approach” to HACCP.

The process approach can best be described as dividing the many foods flows in an establishment into broad categories based on activities or stages in the flow of food through your establishment, then analyzing the hazards, and placing managerial controls on each grouping.

What is the flow of food?

The flow of food in a retail or food service establishment is the path that food follows from receiving through service or sale to the consumer. Several activities or stages make up the flow of food and are called operational steps. Examples of operational steps include receiving, storing, preparing, cooking, cooling, reheating, holding, assembling, packaging, serving, and selling. Keep in mind that the terminology used for operational steps may differ between food service and retail food store operations.

What are the three food preparation processes most often used in retail and food service establishments?

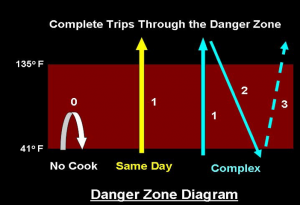

Most food items produced in a retail or food service establishment can be categorized into one of three preparation processes based on the number of times the food passes through the temperature danger zone between 41 ºF to 135 ºF:

• Process 1: Food Preparation with No Cook Step Example flow: Receive – Store – Prepare – Hold – Serve

(other food flows are included in this process, but there is no cook step to destroy pathogens)

• Process 2: Preparation for Same Day Service

Example flow: Receive – Store – Prepare – Cook – Hold – Serve

(other food flows are included in this process, but there is only one trip through the temperature danger zone)

• Process 3: Complex Food Preparation

Example flow: Receive – Store – Prepare – Cook – Cool – Reheat – Hot Hold – Serve

(other food flows are included in this process, but there are always two or more complete trips through the temperature danger zone)

Long description: A graph with Y axis that goes from 41 degrees Fahrenheit to 135 degrees. 3 arrows are shown. The left arrow is labeled No cook and has a zero above it. It starts on the X axis, goes less than halfway up, then curves and comes back down to the X axis. The middle arrow is labeled Same Day and starts on the X axis and goes straight up and off the graph. The number 1 is beside it. The arrow on the right is composed of 3 separate arrows labeled 1, 2 and 3. Arrow 1 goes straight up and off the graph. Arrow 2 starts at the top where arrow 1 ended and comes down diagonally to the X axis. Arrow 3 is dashed and starts where arrow 2 ended. It goes diagonally up and off the graph.

End long description.

A summary of the three food preparation processes in terms of number of times through the temperature danger zone can be depicted in a Danger Zone diagram. Note that while foods produced using process 1 may enter the danger zone, they are neither cooked to destroy pathogens, nor are they hot held. Foods that go through the danger zone only once are classified as Same Day Service, while foods that go through more than once are classified as Complex food preparation.

The three food preparation processes conducted in retail and food service establishments are not intended to be all-inclusive. For instance, quick service facilities may have “cook and serve” processes specific to their operation. These processes are likely to be different from the “Same Day Service” preparation processes in full-service restaurants since many of their foods are generally cooked and hot held before service. In addition, in retail food stores, operational steps such as packaging and assembly may be included in all of the food preparation processes prior to being sold to the consumer.

It is also very common for a retail or food service operator to have a single menu item (i.e. chicken salad sandwich) that is created by combining several components produced using more than one kind of food preparation process. It is important for you to remember that even though variations of the three food preparation process flows are common, the control measures – actions or activities that can be used to prevent, eliminate, or reduce food safety hazards – to be implemented in each process will generally be the same based on the number of times the food goes through the temperature danger zone.

THE HAZARD ANALYSIS

In the “process approach” to HACCP, conducting a hazard analysis on individual food items is time and labor-intensive and is generally unnecessary. Identifying and controlling the hazards in each food preparation process listed above achieves the same control of risk factors as preparing a HACCP plan for each individual product.

Example: An establishment has dozens of food items (including baked chicken and meatloaf) in the “Preparation for Same Day Service” category. Each of the food items may have unique hazards (See Annex 3, Table 1), but regardless of their individual hazards, control via proper cooking and holding will generally ensure the safety of all of the foods in this category. An illustration of this concept follows:

- Even though they have unique hazards, baked chicken and meatloaf are items frequently grouped in the “Same Day Service” category (Process 2).

- Salmonella and Campylobacter, as well as spore-formers, such as Bacillus cereus and Clostridium perfringens, are significant biological hazards in chicken.

- Significant biological hazards in meatloaf include Salmonella, E. coli O157:H7,

- Bacillus cereus, and Clostridium perfringens.

- Despite their different hazards, the control measure used to kill pathogens in both these products should be cooking to the proper temperature.

- Additionally, if the products are held after cooking, then proper hot holding or time control is also recommended to prevent the outgrowth of spore-formers that are not destroyed by cooking.

As with product-specific HACCP, critical limits for cooking remain specific to each food item in the process. In the scenario described above, the cooking step for chicken requires a final internal temperature of 165 ºF for 15 seconds to control the pathogen load for Salmonella. Meatloaf, on the other hand, is a ground beef product and requires a final internal temperature of 155 ºF for 15 seconds to control the pathogen load for both Salmonella and E. coli O157:H7. Note that there are some operational steps, such as refrigerated storage or hot holding, that have critical limits that apply to all foods.

The following table further illustrates this concept. Note that the only unique control measure applies to the critical limit of the cooking step for each of the products. Other food safety hazards and control measures may exist:

[table id=2 /]

Chapter 5, Figure 2

DETERMINING RISK FACTORS IN PROCESS FLOWS

Several of the most common risk factors associated with each food preparation process are discussed below. Remember that while you should generally focus your food safety management system on these risk factors, there may be other risk factors unique to your operation or process that are not listed here. You should evaluate your operation and the food preparation processes you use independently.

In developing your food safety management system, keep in mind that active managerial control of risk factors common to each process can be achieved by either designating certain operational steps as critical control points (CCPs) or by implementing prerequisite programs. This will be explained in more detail in Chapter 3. The HACCP plans that you will develop using this Manual, in combination with prerequisite programs, will constitute a complete food safety management system.

Facility-wide considerations in order to have active managerial control over personal hygiene and cross-contamination, you must implement certain control measures in all phases of your operation. All of the following control measures should be implemented regardless of the food preparation process used:

- No bare hand contact with ready-to-eat foods (or use of an approved, alternative procedure) to help prevent the transfer of viruses, bacteria, or parasites from hands

- Proper handwashing to help prevent the transfer of viruses, bacteria, or parasites from hands to food

- Restriction or exclusion of ill employees to help prevent the transfer of viruses, bacteria, or parasites from hands to food

- Prevention of cross-contamination of ready-to-eat food or clean and sanitized food-contact surfaces with soiled cutting boards, utensils, aprons, etc. or raw animal foods

Food Preparation Process 1 – Food Preparation with No Cook Step

Example Flow: RECEIVE – STORE – PREPARE – HOLD – SERVE

Several food flows are represented by this particular process. Many of these food flows are common to both retail food stores and food service facilities, while others only apply to retail operations. Raw, ready-to-eat food like sashimi, raw oysters, and salads are grouped in this category. Components of these foods are received raw and will not be cooked prior to consumption.

Foods cooked at the processing level but that undergo no further cooking at the retail level before being consumed are also represented in this category. Examples of these kinds of foods are deli meats, cheeses, and other pasteurized products. In addition, foods that are received and sold raw but are to be cooked by the consumer after purchase, i.e. hamburger meat, chicken, and steaks, are also included in this category.

All the foods in this category lack a kill (cook) step while at the retail or food service establishment. In other words, there is no complete trip made through the danger zone for the purpose of destroying pathogens. You can ensure that the food received in your establishment is as safe as possible by requiring purchase specifications. Without a kill step to destroy pathogens, your primary responsibility will be to prevent further contamination by ensuring that your employees follow good hygienic practices.

Cross-contamination must be prevented by properly storing your products away from raw animal foods and soiled equipment and utensils. Foodborne illness may result from ready-to-eat food being held at unsafe temperatures for long periods of time due to the outgrowth of bacteria.

In addition to the facility-wide considerations, a food safety management system involving this food preparation process should focus on ensuring that you have active managerial control over the following:

- Cold holding or using time alone to inhibit bacterial growth and toxin production

- Food source (especially for shellfish due to concerns with viruses, natural toxins, and Vibrio and for certain marine finfish intended for raw consumption due to concerns with ciguatera toxin) (See Annex 2, Table 1)

- Receiving temperatures (especially certain species of marine finfish due to concerns with scombrotoxin) (See Annex 2, Table 2)

- Date marking of ready-to-eat PHF held for more than 24 hours to control the growth of Listeria monocytogenes

- Freezing certain species of fish intended for raw consumption due to parasite concerns (See Annex 2, Table 3)

- Cooling from ambient temperature to prevent the outgrowth of spore-forming or toxin-forming bacteria

Food Preparation Process 2 – Preparation for Same Day Service

Example Flow: RECEIVE – STORE – PREPARE – COOK – HOLD – SERVE

In this food preparation process, food passes through the danger zone only once in the retail or food service establishment before it is served or sold to the consumer. Food is usually cooked and held hot until served, i.e. fried chicken, but can also be cooked and served immediately. In addition to the facility-wide considerations, a food safety management system involving this food preparation process should focus on ensuring that you have active managerial control over the following:

- Cooking to destroy bacteria and parasites

- Hot holding or using time alone to prevent the outgrowth of spore-forming bacteria

Approved food source, proper receiving temperatures, and proper cold holding prior to cooking are also important if dealing with certain marine finfish due to concerns with ciguatera toxin and scombrotoxin. Consult Annex 2 of this Manual for special considerations related to seafood.

Food Preparation Process 3 – Complex Food Preparation

Example Flow: RECEIVE – STORE – PREPARE – COOK – COOL – REHEAT – HOT HOLD – SERVE

Foods prepared in large volumes or in advance for next day service usually follow an extended process flow. These foods pass through the temperature danger zone more than one time; thus, the potential for the growth of spore-forming or toxigenic bacteria is greater in this process.

Failure to adequately control food product temperatures is one of the most frequently encountered risk factors contributing to foodborne illness. In addition, foods in this category have the potential to be recontaminated with L. monocytogenes, which could grow during refrigerated storage. FDA recommends that food handlers minimize the time foods are at unsafe temperatures.

In addition to the facility-wide considerations, a food safety management system involving this food preparation process should focus on ensuring that you have active managerial control over the following:

- Cooking to destroy bacteria and parasites

- Cooling to prevent the outgrowth of spore-forming or toxin-forming bacteria

- Hot and cold holding or using time alone to inhibit bacterial growth and toxin formation

- Date marking of ready-to-eat PHF held for more than 24 hours to control the growth of Listeria monocytogenes

- Reheating for hot holding, if applicable

Approved food source, proper receiving temperatures, and proper cold holding prior to cooking are also important if dealing with certain marine finfish due to concerns with ciguatera toxin and scombrotoxin. Consult Annex 2 of this Manual for special considerations related to seafood.

Summary

Implementing a HACCP plan in retail and onsite foodservice operations is not always required by regulation, but it is considered a “best practice.” The menu drives the type of systems that need to be implemented. Recipes for each menu item need to be standardized and “HACCP-itized” for each individual operation based on the flow of food, equipment and employees. Effective foodservice managers understand the importance of establishing a food safety culture and HACCP plan within an organization, and also how doing so will help reduce risks, control costs, and improve operations overall.

Definitions from the 2017 U.S. Food Code:

“Critical control point” means a point or procedure in a specific FOOD system where loss of control may result in an unacceptable health RISK.

“Critical limit” means the maximum or minimum value to which a physical, biological, or chemical parameter must be controlled at a CRITICAL CONTROL POINT to minimize the RISK that the identified FOOD safety HAZARD may occur.

“HACCP plan” means a written document that delineates the formal procedures for following the HAZARD Analysis and CRITICAL CONTROL POINT principles developed by The National Advisory Committee on Microbiological Criteria for Foods.

“Hazard” means a biological, chemical, or physical property that may cause an unacceptable CONSUMER health RISK.

“Time/temperature control for safety food” means a FOOD that requires time/temperature control for safety (TCS) to limit pathogenic microorganism growth or toxin formation.

“Time/temperature control for safety food” includes:

(a) An animal FOOD that is raw or heat-treated; a plant FOOD that is heat-treated or consists of raw seed sprouts, cut melons, cut leafy greens, cut tomatoes or mixtures of cut tomatoes that are not modified in a way so that they are unable to support pathogenic microorganism growth or toxin formation, or garlic-in-oil mixtures that are not modified in a way so that they are unable to support pathogenic microorganism growth or toxin formation.

Review Exercise 1

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.

Review Exercise 2

The original version of this chapter contained H5P content. You may want to remove or replace this element.