3.5: Storing Fish and Shellfish

- Page ID

- 21276

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Determining Freshness

Because fish and shellfish are highly perishable, an inspection stamp does not necessarily ensure top quality. A few hours at the wrong temperature or a couple of days in the refrigerator can turn high-quality fish or shellfish into garbage. It is important that chefs be able to determine for themselves the freshness and quality of the fish and shellfish they purchase or use. Freshness should be checked before purchasing and again just before cooking.

Determined freshness by the following criteria:

- Smell - This is by far the easiest way to determine freshness. Fresh fish should have aslight sea smell or no odor at all. Any off-odors or ammonia odors are a sure sign of aged or improperly handled fish.

- Eyes - The eyes should be clear and full. Sunken eyes mean that the fish is drying out and is probably not fresh.

- Gills - The gills should be intact and bright red. Brown gills are a sign of age.

- Texture - Generally, the flesh of fresh fish should be firm. Mushy flesh or flesh that does not spring back when pressed with a finger is a sign of poor quality or age.

- Fins and scales - Fins and scales should be moist and full without excessive drying on the outer edges. Dry fins or scales are a sign of age; damaged fins or scales may be a sign of mishandling.

- Appearance - Fish cuts should be moist and glistening, without bruises or dark spots. Edges should not be brown or dry.

- Movement - Shellfish should be purchased live and should show movement. Lobsters and other crustaceans should be active. Clam s, mussels and oysters that are partially opened should snap shut when tapped with a finger. (Exceptions are geoduck, razor and steamer clams whose siphons protrude, preventing the shell from closing completely.) Ones that do not close are dead and should not be used. Avoid mollusks with broken shells or heavy shells that might be filled with mud or sand.

Purchasing Fish and Shellfish

Fish are available from wholesalers in a variety of market forms:

- Whole or round - As caught, intact.

- Drawn-Viscera - (internal organs) are removed; most whole fish are purchased this way.

Seafood Terminology

- Fresh - The item is not and has never been frozen.

- Chilled - Now used by some in the industry to replace the more ambiguous "fresh"; indicates that the item was refrigerated, that is, held at 30°F to 34°F (- 1°C to 1 ° C).

- Flash-frozen - The item was quickly frozen on board the ship or at a processing plant within hours of being caught.

- Fresh-frozen - The item was quick-frozen while still fresh but not as quickly as flash- frozen.

- Frozen - The item was subjected to temperatures of 0°F (- 18°C) or lower to pre- serve its inherent quality.

- Glazed - A frozen product dipped in water; the ice forms a glaze that protects the item from freezer burn.

- Fancy - Code word for "previously frozen."

- Dressed - Viscera, gills, fins and scales are removed.

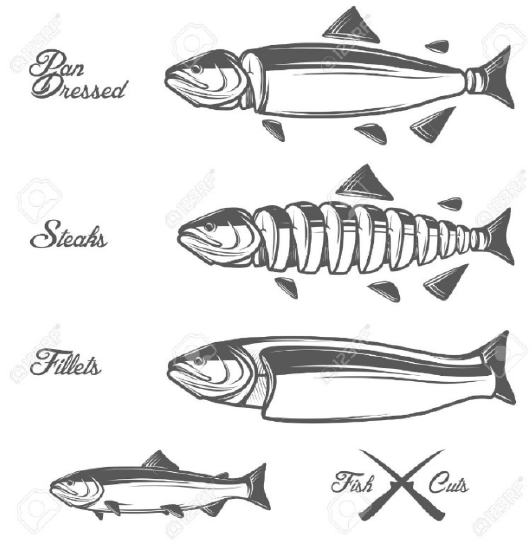

- Pan-dressed - Viscera and gills are removed; fish is scaled and fins and tail are trimmed. The head is usually removed, although small fish, such as trout, may be pan-dressed with the head still attached. Pan -dressed fish are then pan-fried.

- Butterflied - A pan-dressed fish, boned and opened flat like a book. The two sides remain attached by the back or belly skin.

- Fillet - The side of a fish removed intact, boneless or semiboneless, with or without skin.

- Steak - A cross-section slice, with a small section of backbone attached; usually prepared from large round fish such as salmon, swordfish or tuna.

- Wheel or center-cut - Used for swordfish and sharks, which are cut into large boneless pieces from which steaks are then cut.

Chefs purchase fish in the market forms most practical for each operation. Although fish fabrication is a relatively simple chore requiring little specialized equipment, before deciding to cut fish on premises, consider the following:

- The food service operation's ability to utilize the bones and trim that cutting whole fish produces

- The employees' ability to fabricate fillets, steaks or portions as needed

- The storage facilities

- The product's intended use

Most shellfish can be purchased live in the shell, shucked (the meat re- moved from the shell) or processed. Both live and shucked shellfish are usually purchased by counts (that is, the number per volume). For example, standard live Eastern oysters are packed 200 to 250 (the count) per bushel (the unit of volume); standard Eastern oyster meats are packed 350 per gallon. Crustaceans are sometimes packed by size based on the number of pieces per pound; for example, crab legs or shrimp are often sold in counts per pound. Crustaceans are also sold either by grades based on size (whole crabs) or by weight (lobsters).

The most important concern when storing fish and shellfish is temperature. All fresh fish should be stored at temperatures between 30°F and 34°F (- 1°C to 1°C). Fish stored in a refrigerator at 41°F (5°C) will have approximately half the shelf life of fish stored at 32°F (0°C).

Most fish are shipped on ice and should be stored on ice in the refrigerator as soon as possible after receipt. Whole fish should be layered directly in crushed or shaved ice in a perforated pan so that the melted ice water drains away. If crushed or shaved ice is not available, cubed ice may be used provided it is put in plastic bags and gently placed on top of the fish to prevent bruising and denting. Fabricated and portioned fish may be wrapped in moisture-proof packaging before icing to prevent the ice and water from damaging the exposed flesh. Fish stored on ice should be drained and re-iced daily.

Fresh scallops, fish fillets that are purchased in plastic trays and oyster and clam meats should be set on or packed in ice. Do not let the scallops, fillets or meats come into direct contact with the ice.

Clams, mussels and oysters should be stored at 41°F (5°C), at high humidity and left in the boxes or net bags in which they were shipped. Under ideal conditions, shellfish can be kept alive for up to one week. Never store live shellfish in plastic bags and do not ice them.

If a saltwater tank is not available, live lobsters, crabs and other crustaceans should be kept in boxes with seaweed or damp newspaper to keep them moist. Most crustaceans circulate salt water over their gills; icing them or placing them in fresh water will kill them. Lobsters and crabs will live for several days under ideal conditions.

Like most frozen foods, frozen fish should be kept at temperatures of 0°F (-18°C) or colder. Colder temperatures greatly increase shelf life. Frozen fish should be thawed in the refrigerator; once thawed, they should be treated like fresh fish.

This procedure is used to remove the scales from fish that will be cooked with the skin on.

- Place the fish on a work surface or in a large sink.

- Grip the fish by the tail and, working from the tail toward the head, scrape the scales off with a fish scaler or the back of a knife. Be careful not to damage the flesh by pushing too hard.

- Turn the fish over and remove the scales from the other side.

- Rinse the fish under cool water.

- Place the scaled fish on a cutting board and remove the head by making a V-shaped cut around it with a chef's knife. Pull the head away and remove the viscera.

- Rinse the fish under cold water, removing all traces of blood and viscera from the cavity.

- Using a pair of kitchen shears, trim off the tail and all of the fins.

Round fish produce two fillets, one from either side.

- Using a chef's knife, cut down to the backbone just behind the gills. Do not remove the head.

- Turn the knife toward the tail; using smooth strokes, cut from head to tail, parallel to the backbone. The knife should bump against the backbone so that no flesh is wasted; you will feel the knife cutting through the small pin bones. Cut the fillet completely free from the bones. Repeat on the other side.

- Trim the rib bones from the fillet with a flexible boning knife.

Flatfish produce four fillets: two large bilateral fillets from the top and two smaller bilateral fillets from the bottom. If the fish fillets are going to be cooked with the skin on, the fish should be scaled before cooking (it is easier to scale the fish before it is filleted). If the skin is going to be removed before cooking, it is not necessary to scale the fish.

- With the dark side of the fish facing up, cut along the backbone from head to tail with the

tip of a flexible boning knife. - Turn the knife and, using smooth strokes, cut between the flesh and the rib bones, keeping the flexible blade against the bone. Cut the fillet completely free from the fish. Remove the second fillet, following the same procedure.

- Turn the fish over and remove the fillets from the bottom half of the fish, following the same procedure.

Dover sole is unique in that its skin can be pulled from the whole fish with a simple procedure. The flesh of other small flatfish such as flounder, Petrale sole and other types of domestic sole is more delicate; pulling the skin away from the whole fish could damage the flesh. These fish should be skinned after they are filleted.

- Make a shallow cut in the flesh perpendicular to the length of the fish, just in front of the tail and with the knife angled toward the head of the fish.

- Using a clean towel, grip the skin and pull it toward the head of the fish. The skin should come off cleanly, in one piece, leaving the flesh intact.

Use the same procedure to skin all types of fish fillets.

- Place the fillet on a cutting board with the skin side down.

- Starting at the tail, use a meat slicer or a chef's knife to cut between the flesh and skin.

- Angle the knife down toward the skin, grip the skin tightly with one hand and use a smooth sawing motion to cut the skin cleanly away from the flesh.

Round fish fillets contain a row of intramuscular bones running the length of the fillet. Known as pin bones, they are usually cut out with a knife to produce bone- less fillets. In the case of salmon, they can be removed with salmon tweezers or small needle -nose pliers.

- Place the fillet (either skinless or not) on the cutting board, skin side down.

- Starting at the front or head end of the fillet, use your fingertips to locate the bones and use the pliers to pull them out one by one.

Various Cooking Methods. Fish and shellfish can be prepared by the dry-heat cooking methods of broiling and grilling, roasting (baking ), sautéing, pan-frying and deep-frying , as well as the moist-heat cooking methods of steaming, poaching and simmering.

Determining Doneness

Unlike most meats and poultry, nearly all fish and shellfish are inherently tender and should be cooked just until done. Indeed, overcooking is the most common mistake made when preparing fish and shellfish. The Canadian Department of Fisheries recommends that all fish be cooked 10 minutes for every inch (2.5 centimeters) of thickness, regardless of cooking method. Although this may be a good general policy, variables such as the type and the form of fish and the exact cooking method used suggest that one or more of the following methods of determining doneness are more appropriate for professional food service operations:

- Translucent flesh becomes opaque -The raw flesh of most fish and shellfish appears somewhat translucent. As the proteins coagulate during cooking, the flesh becomes opaque.

- Flesh becomes firm - The flesh of most fish and shellfish firms as it cooks. Doneness can be tested by judging the resistance of the flesh when pressed with a finger. Raw or undercooked fish or shellfish will be mushy and soft. As it cooks, the flesh offers more resistance and springs back quickly.

- Flesh separates from the bones easily - The flesh of raw fish remains firmly attached to the bones. As the fish cooks, the flesh and bones separate easily.

- Flesh begins to flake - Fish flesh consists of short muscle fibers separated by thin connective tissue. As the fish cooks, the connective tissue breaks down and the groups of muscle fibers begin to flake, that is, separate from one another. Fish is done when the flesh begins to flake. If the flesh flakes easily, the fish will be overdone and dry.

Remember, fish and shellfish are subject to carryover cooking. Because they cook quickly and at low temperatures, it is better to undercook fish and shell- fish and allow carryover cooking or residual heat to finish the cooking process.