11.1: Introduction to Shell Fish

- Page ID

- 21266

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Many shellfish species are very expensive; all are highly perishable. Because their cooking times are generally shorter and their flavors more delicate than meat or poultry, special attention must be given to fish and shellfish to prevent spoilage and to produce high-quality finished products.

STRUCTURE and MUSCLE COMPOSITION

Mollusks are shellfish characterized by soft, unsegmented bodies with no internal skeleton. Most mollusks have hard outer shells. Single- shelled mollusks such as abalone are known as univalves. Those with two shells, such as clams, oysters and mussels, are known as bivalves. Squid and octopus, which are known as cephalopods, do not have a hard outer shell. Rather, they have a single thin internal shell called a pen or cuttlebone.

Crustaceans are also shellfish. They have a hard outer skeleton or shell and jointed appendages. Crustaceans include lobsters, crabs and shrimp.

The flesh of fish and shellfish consists primarily of water, protein, fat and minerals. Fish flesh is composed of short muscle fiber s separated by delicate sheets of connective tissue. Fish, as well as most shellfish, are naturally tender, so the purpose of cooking is to firm proteins and enhance flavor. The absence of the oxygen-carrying protein myoglobin makes fish flesh very light or white in color. (The orange color of salmon and some trout comes from pigments found in their food.) Compared to meats, fish do not contain large amounts of intermuscular fat. However, the amount of fat a fish does contain affects the way it responds to cooking. Fish containing a relatively large amount of fat, such as salmon and mackerel, are known as fatty or oily fish. Fish such as cod and haddock contain very little fat and are referred to as lean fish. Shellfish are also very lean.

IDENTIFYING SHELLFISH

Identifying fish and shellfish properly can be difficult because of the vast number of similar- appearing fish and shellfish that are separate species within each family. Adding confusion are the various colloquial names given to the same fish or the same name given to different fish in different localities. Fish with an un-appealing name may also be given a catchier name or the name of a similar but more popular item for marketing purposes. Moreover, some species are referred to by a foreign name, especially on menus.

The FDA publishes a list of approved market names for food fish in The Seafood List: FDA Guide to Acceptable Market Names for Food Fish Sold in Inter- state Commerce 2002. The list is updated regularly and available on the FDA's Web site at the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. Deviations from this list are strongly discouraged but difficult to enforce. We attempt to use the most common names for each item, whether they are zoologically accurate or not.

MOLLUSKS

Univalves

Univalves are mollusks with a single shell in which the soft-bodied animal resides. They are actually marine snails with a single foot, used to attach the creature to fixed objects such as rocks.

Abalone Discus Abalone Breakfast

Abalone have brownish-gray, ear-shaped shells. They are harvested in California, but California law does not permit canning abalone or shipping it out of state. Some frozen abalone is available from Mexico; canned abalone is imported from Japan. Abalone are lean with a sweet, delicate flavor similar to that of clams. They are too tough to eat unless tenderized with a mallet or rolling pin. They may then be eaten raw or prepared ceviche -style. Great care must be taken when grilling or sautéing abalone, as the meat becomes very tough when overcooked

Conch

Conch are found in warm waters off the Florida Keys and in the Caribbean. Beachcombers prize the beautiful peachy-pink shell of the queen conch. Conch meat is lean, smooth and very firm with a sweet-smoky flavor and chewy texture. It can be sliced and pounded to tenderize it, eaten raw with lime juice or slow-cooked whole.

Small Escargot Snails

Snails. Although snails (more politely known by their French name, escargots) are univalve land animals, they share many characteristics with their marine cousins. They can be poached in court bouillon; removed from their shells and boiled; or baked briefly with a seasoned butter, or sauce. They should be firm but tender; overcooking makes snails tough and chewy. The most popular varieties are the large white Burgundy snail and the small garden variety called petit gris.

Fresh snails are available from snail ranches through specialty suppliers. The great majority of snails, however, are available canned; most canned snails are the product of France or Taiwan.

Bivalves

Bivalves are mollusks with two bilateral shells attached by a central hinge.

Calms Clam shell

Clams are harvested along both the East and West Coasts, with Atlantic clams being more significant commercially. Atlantic Coast clams include hard-shell, soft-shell and surf clams. Clams are available all year, either live in the shell or fresh -shucked (meat removed from the shell). Canned clams, whether minced, chopped, or whole, are also available.

Atlantic hard-shell clams or quahogs have hard, blue-gray shells. Their chewy meat is not as sweet as other clam meat. Quahogs have different names, depending upon their size. Littlenecks are generally under 2 inches (5 centimeters) across the shell and usually are served on the half shell or steamed. They are the most expensive clams.

Cherrystones are generally under 3 inches (7.5 centimeters) across the shell and are sometimes eaten raw but are more often cooked.

Top necks are usually cooked and are often served as stuffed clams.

Chowders, the largest quahogs, are always eaten cooked, especially minced for chowder or soup.

Soft-shell clams, also known as Ipswich, steamer and long-necked clams, have thin, brittle shells that do not completely close because of the clam's protruding black-tipped siphon. Their meat is tender and sweet. They are sometime s fried but are more often served steamed.

Surf clams are deep-water clams that reach sizes of 8 inches (20 centimeters) across. They are most often cut into strips for frying or are minced, chopped, processed and canned.

Pacific clams are generally too tough to eat raw. The most common is the Manila clam, which was introduced along the Pacific coast during the 1930s. Resembling a quahog with a ridged shell, it can be served steamed or on the half shell. Geoducks are the largest Pacific clam, sometimes weighing up to 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) each. They look like huge soft-shell clams with a large, protruding siphon. Their tender, rich bodies and briny flavor are popular in Asian cuisines.

Cockles

Cockles are small bivalves, about 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long, with ridged shells. They are more popular in Europe than the United States and are sometimes used in dishes such as paella and fish soups or stews.

Mussels

Mussels are found in waters worldwide. They are excellent steamed in wine or seasoned broth and can be fried or used in soups or pasta dishes.

Blue mussels are the most common edible mussel. They are found in the wild along the Atlantic Coast and are aqua- farmed on both coasts. Their meat is plump and sweet with a firm, muscular texture. The orangey-yellow meat of cultivated mussels tends to be much larger than that of wild mussels and therefore worth the added cost. Blue mussels are sold live in the shell and average from 10 to 20 per pound. Although available all year, the best-quality blue mussels are harvested during the winter months.

Green shell (or green lip) mussels from New Zealand and Thailand are much larger than blue mussels, averaging 8 to 12 mussels per pound. Their shells are paler gray, with a distinctive bright green edge

Oysters

Oysters have a rough gray shell. Their soft, gray, briny flesh can be eaten raw directly from the shell. They can also be steamed or baked in the shell or shucked and fried, sautéed or added to stews or chowders. Most oysters available in the United States are commercially grown and sold either live in the shell or shucked. There are four main domestic species.

Atlantic oysters, also called American or Eastern oysters, have darker, flatter shells than other oysters.

European flat oysters are often incorrectly called Belon (true Belon oysters live only in the Belon river of France); they are very round and flat and look like giant brownish-green Olympias.

Olympias are the only oysters native to the Pacific Coast; they are tiny (about the size of a 50-cent coin).

Pacific oysters, also called Japanese oysters, are aqua - farmed along the Pacific Coast; they have curly, thick striated shells and silvery-gray to gold to almost -white meat. Although it may seem as though there are hundreds of oyster species on the market, only two are commercially significant: the Atlantic oyster and the Pacific oyster. These two species yield dozens of different varieties, however, depending on their origin. For example, Atlantic oysters may be referred to as blue points, Chesapeake Bay, Florida Gulf, Long Island and so on, while Pacific oysters include Penn Cove Select, Westcott Bay, Hamma-Hamma, Kumamoto and Portuguese, among others. An oyster's flavor reflects the minerals, nutrients and salts in its water and mud bed, so a Bristol from Maine and an Apalachicola from Florida will taste very different, even though they are the same Atlantic species.

Scallops contain an edible white adductor muscle that holds together the fan -shaped shells. Because they die quickly, they are usually shucked, and cleaned on board the ship. The sea

scallop and the bay scallop, both cold-water varieties, and the calico scallop, a warm-water variety, are the most important commercially. Sea scallops are the largest, with an average count of 20 to 30 per pound. Larger sea scallops are also available.

Bay scallops average 70 to 90 per pound; calico scallops average 70 to 110 per pound. Fresh or frozen shucked, cleaned scallops are the most common market form, but live scallops in the shell and shucked scallops with roe attached (very popular in Europe) are also available. Scallops are sweet, with a tender texture. Raw scallops should be a translucent ivory color and non- symmetrically round and should feel springy. They can be steamed, broiled, grilled, fried, sautéed, or baked. When overcooked, however, scallops quickly become chewy and dry. Only extremely fresh scallops should be eaten raw.

CEPHALOPODS

Cephalopods are marine mollusks with distinct heads, well-developed eyes, a number of arms that attach to the head near the mouth and a saclike fin-bearing mantle. They do not have an outer shell; instead, there is a thin internal shell called a pen or cuttlebone.

Octopus is generally quite tough and requires mechanical tenderization or long, moist-heat cooking to make it palatable. Most octopus is imported from Portugal, though fresh ones are available on the East Coast during the winter. Octopus is sells by the pound usually fresh, frozen, or whole. Octopus skin is gray when raw, turning purple when cooked. The interior flesh is white, lean, firm and flavorful.

Squid, known by their Italian name, calamari, are becoming increasingly popular in the United States. Similar to octopuses but much smaller, they are harvested along both American coasts and elsewhere around the world, (the finest are the East Coast loligo or winter squid). They range in size from an average of 8 to 10 per pound to the giant South American squid, which is sold as tenderized steaks. The squid's tentacles, mantle (body tube) and fins are edible. Squid meat is white to ivory in color, turning darker with age. It is moderately lean, slightly sweet, firm and tender, but it toughens quickly if overcooked. Squid are available either fresh or frozen and packed in blocks.

CRUSTACEANS

Crustaceans are found in both fresh and salt water. They have a hard outer shell and jointed appendages, and they breathe through gills.

Crawfish Boiled Crawfish

Crayfish generally called crayfish in the North and ‘crawfish’ or ‘crawdad’ in the South, are freshwater creatures that look like miniature lobsters. They are harvested from the wild or aqua farmed in Louisiana and the Pacific Northwest. They are from 3 1/2 to 7 inches (8 to 17.5 centimeters) in length when marketed and may be purchased live or precooked and frozen. The lean meat, found mostly in the tail, is sweet and tender. Crayfish can be boiled whole, and served hot or cold. The tail meat can be deep-fried, or used in soups, bisque or sauces. Crayfish are a staple of Cajun cuisine, often used in gumbo, etouffee and jambalaya. Whole crayfish become brilliant red when cooked, and useful as a garnish

Atlantic blue crab Snow crab

Dungeness crab Stone crab

Alaskan king crab

Crabs are found along the North American coast in great numbers and are shipped throughout the world in fresh, frozen and canned forms. Crab meat varies in flavor and texture and can be used in a range of prepared dishes, from chowders to curries to casseroles. Crabs purchased live should last up to five days; dead crabs should not be used.

King crabs are very large crabs (usually around 10 pounds [4.4 kilograms] caught in the very cold waters of the northern Pacific. Their meat is very sweet and snow-white. King crabs are always sold frozen, usually in the shell. In-shell forms include sections or clusters legs and claws or split legs. The meat is also available in "fancy" packs of whole leg and body meat, or shredded and minced pieces.

Dungeness crabs are found along the West Coast. They weigh 1 1/2 to 4 pounds (680 grams to 1.8 kilograms) and have delicate, sweet meat. They are sold live, precooked and frozen, or as picked meat, usually in 5-pound (2.2 -kilogram) vacuum - packed cans.

Blue crabs are found along the entire eastern seaboard and account for approximately 50 percent of the total weight of all crab species harvested in the United States. Their meat is rich and sweet. Blue crabs are available as hard-shell or soft-shell. Hard-shell crabs are sold live, precooked and frozen, or as picked meat. Soft-shell crabs are those harvested within six hours after molting and are available live (generally only from May 15 to September 15) or frozen . They are often steamed and served whole. Soft-shells can be sautéed, fried, broiled or added to soups or stews. Blue crabs are sold by size, with an average diameter of 4 to 7 inches (10 to 18 centimeters).

Snow or spider crabs are an abundant species, most often used as a substitute for the scarcer and more expensive king crab. They are harvested from Alaskan waters and along the eastern coast of Canada. Snow crab is sold precooked, usually frozen. The meat can be used in soups, salads, omelets or other pre- pared dishes. Legs are often served cold as an appetizer.

Stone crabs are generally available only as cooked claws, either fresh or frozen (the claws cannot be frozen raw because the meat sticks to the shell). In stone crab fishery, only the claw is harvested. After the claw is removed, the crab is returned to the water, where in approximately 18 months it regenerates a new claw. Claws average 2 1/2 to 5 1/2 ounces (75 to 155 grams) each. The meat is firm, with a sweet flavor similar to lobster. Cracked claws are served hot or cold, usually with cocktail sauce, lemon butter, or other accompaniments.

Lobster

Lobsters have brown to blue -black outer shells and firm, white meat with a rich, sweet flavor. Lobster shells turn red when cooked. They are usually poached, steamed, simmered, baked or grilled, and can be served hot or cold. Picked meat can be used in prepared dishes, soups or sautés. Lobsters must be kept alive until just before cooking. Dead lobsters should not be eaten. The Maine, also known as American or clawed lobster, and the spiny lobster are the most commonly marketed species.

Maine lobsters have edible meat in both their tails and claws; they are considered superior in flavor to all other lobsters. They come from the cold waters along the northeast coast and are most often sold live. Maine lobsters may be purchased by weight (for example, 1 1/4 pounds [525 grams], 1 1/2 pounds [650 grams] or 2 pounds [900 grams] each), or as 'chix' (that is, a lobster weighing less than 1 pound [450 grams]). Maine lobsters may also be purchased as ‘culls’ (lobsters with only one claw) or ‘bullets’ (lobsters with no claws). They are available frozen or as cooked, picked meat

Spiny Lobster

Spiny lobsters, harvested in many parts of the world, have very small claws and are valuable only for their meaty tails, which are notched with short spines. Nearly all spiny lobsters marketed in this country are sold as frozen tails, often identified as rock lobster. Those found off Florida and Brazil and in the Caribbean are marketed as warm-water tails; those found off South Africa, Australia and New Zealand are called cold-water tails. Cold-water spiny tails are considered superior to their warm-water cousins.

Slipper lobster, lobsterette, and squat lobster are all clawless species found in tropical, subtropical and temperate waters worldwide. Although they are popular in some countries, their flavor is inferior to that of both Maine and spiny lobsters. Langoustines are small North Atlantic lobsters.

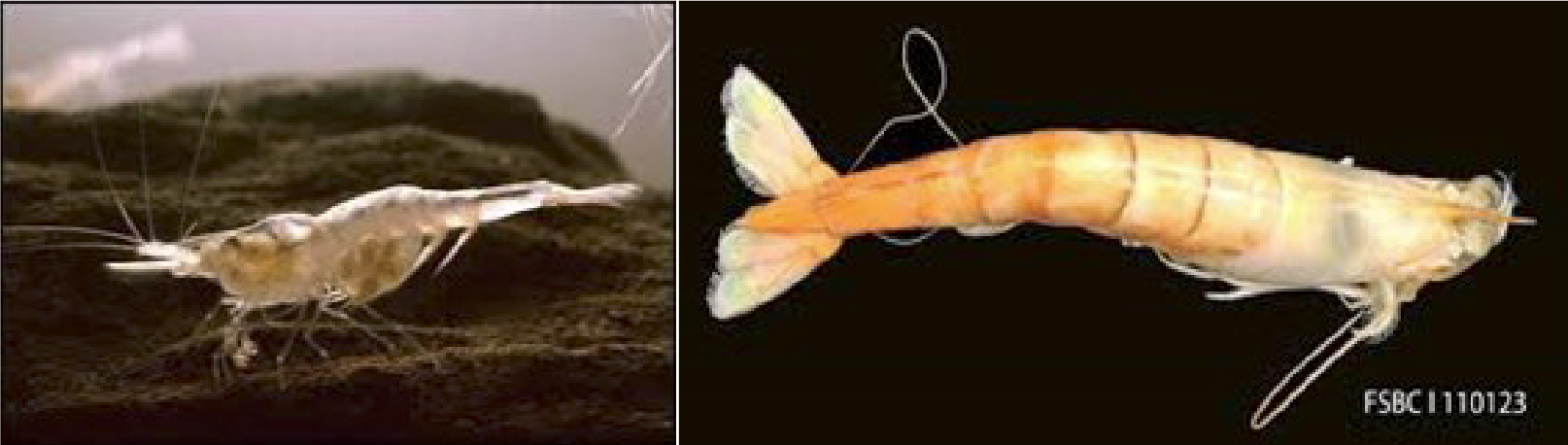

Shrimp Brown shrimp

White shrimp Boiled shrimp

Shrimp are found worldwide and are widely popular. Gulf whites, pinks, browns, and black tigers are just a few of the dozens of shrimp varieties used in food service operations. Although fresh, head-on shrimp are available, the most common form is raw, head-off (also called green headless) shrimp with the shell on. Most shrimp are de-headed and frozen at sea to preserve freshness.

Shrimp are available in many forms: raw, peeled and deveined; cooked, peeled and deveined; and individually quick-frozen, as well as in a variety of processed, breaded or canned products. Shrimp are graded by size, which can range from 400 per pound to 8 per pound (extra-colossal), and are sold in counts per pound. For example, shrimp marketed as "21- 26 count" means that there is an average of 21 to 26 shrimp per pound; shrimp marketed as "U-10" means that there are fewer than 10 shrimp per pound.

Prawns Tiger prawn

Prawn is often used interchangeably with the word shrimp in English speaking countries. Although it is perhaps more accurate to refer to fresh-water species as prawns, and saltwater species as shrimp, in commercial practice, prawn refers to any large shrimp. Equally confusing, scampi is the Italian name for the Dublin Bay prawn (which is actually a species of miniature lobster), but in the United States scampi refers to shrimp sautéed in garlic butter

African Shrimp African Fan Shrimp

Nutrition

Fish and shellfish are low in calories, fat and sodium, and are high in protein and vitamins A, Band D. Fish and shellfish are also high in minerals, especially calcium (particularly in canned fish with edible bones), phosphorus, and potassium and iron (especially mollusks). Fish are high in a group of polyunsaturated fatty acids called omega-3, which may help combat high blood cholesterol levels and aid in preventing some heart disease. Shellfish are not as high in cholesterol as was once thought. Crustaceans are higher in cholesterol than mollusks, but both have considerably lower levels than red meat or eggs.

The cooking methods used for fish and shellfish also contribute to their healthfulness. The most commonly used cooking methods are broiling, grilling, poaching and steaming-add little or no fat.

Inspection

Unlike mandatory meat and poultry inspections, fish and shellfish inspections are voluntary. They are performed in a fee-for-service program supervised by the United States Department of Commerce (USDC).

Type 1-inspection services cover plant, product and processing methods from the raw material to the final product. The "Packed under Federal Inspection" (PUFI) mark or statement can be used on product labels processed under Type 1 inspection services. It signifies that the product is safe and wholesome, is properly labeled, has reasonably good flavor and odor and was produced under

~Procedure for Preparing Live Lobsters for Sautéing~

A whole lobster may also be cut into smaller pieces for sautéing or other preparations.

- Using the point of a chef's knife, pierce the lobster's head.

- Cut off the claws and arms.

- Cut the tail into cross-sections.

- Split the head and thorax in half. The tomalley and coral (if present) can be removed and saved for further use. The head and legs may be added to the recipe for flavor, but there is very little meat in them and they are typically discarded.

- Crack the claws with a firm blow, using the back of a chef's knife.

~Procedure for Opening Clams~

Opening raw clams efficiently requires practice. Like all mollusks, clams should be cleaned under cold running water with a brush to remove all mud, silt and sand that may be stuck to their shells. A knife may be more easily inserted into a clam if the clam is washed and allowed to relax in the refrigerator for at least one hour before it is opened.

- Hold the clam firmly in a folded towel in the palm of your hand; the notch in the edge of the shell should be toward your thumb.

- With the fingers of the same hand, squeeze and pull the blade of the clam knife between the clamshells. Do not push on the knife handle with your other hand; you will not be able to control the knife if it slips and you can cut yourself

- Pull the knife between the shells until it cuts the muscle. Twist the knife to pry the shells apart. Slide the knife tip along the top shell and cut through the muscle. Twist the top shell, breaking it free at the hinge; discard it.

- Use the knife tip to release the clam from the bottom shell.

~Procedure for Opening Oysters~

- Clean the oyster by brushing it under running water.

- Hold the cleaned oyster firmly in a folded towel in the palm of your hand. Insert the tip of an oyster knife in the hinge and use a twisting motion to pop the hinge apart. Do not use too much forward pressure on the knife; it can slip and you could stab yourself

- Slide the knife along the top of the shell to release the oyster from the shell. Discard the top shell.

- Use the knife tip to release the oyster from the bottom shell

- Fresh raw oysters on the half shell with seaweed garnish.

~Procedure for Cleaning and De-bearding Mussels~

Mussels are not normally eaten raw. Before cooking, a clump of dark threads called the beard must be removed. Because this could kill the mussel, cleaning and de-bearding must be clone as close to cooking time as possible.

- Clean the mussel with a brush under cold running water to remove sand and grit.

- Pull the beard away from the mussel with your fingers or a small pair of pliers.

~Procedure for Preparing Live Lobsters for Boiling~

A whole lobster can be cooked by plunging it into boiling water or court bouillon. If the lobster is to be broiled, it must be split lengthwise before cooking.

- Place the live lobster on its back on a cutting board and pierce its head with the point of a chef's knife.

- Then, in one smooth stroke, bring the knife down and cut through the body and tail without splitting it completely in half.

- Use your hands to crack the lobsters back so that it lies flat. Crack the claws with the back of a chef's knife.

- Cut through the tail and curl each half of the tail to the side. Remove and discard the stomach. The tomalley (the olive-green liver) and, if present, the coral (the roe) can be removed and saved for a sauce or other preparation

Various Cooking Methods. Fish and shellfish can be prepared by the dry-heat cooking methods of broiling and grilling, roasting (baking ), sautéing, pan-frying and deep-frying , as well as the moist-heat cooking methods of steaming, poaching and simmering

Packed under Federal Inspection (PUFI)

Type 2-inspection services are usually performed in a warehouse, processing plant or cold storage facility on specific product lots. A lot inspection determines whether the product complies with purchase agreement criteria (usually defined in a spec sheet) such as condition, weight, labeling and packaging integrity.

Type 3-inspection services are for sanitation only. Fishing vessels or plants that meet the requirements are recognized as official establishments and are included in the USDC Approved List of Fish Establishments and Products. The list is available to governmental and institutional purchasing agents as well as to retail and restaurant buyers. Updated copies of the list are published on the Internet.

Grading

Only fish processed under Type 1 inspection services are eligible for grading. Each type of fish has its own grading criteria, but because of the great variety of fish and shellfish, the USDC has been able to set grading criteria for only the most common types. The grades assigned to fish are A, B or C.

Grade A products are top quality and must have good flavor and odor and be practically free of physical blemishes or defects. The great majority of fresh and frozen fish and shellfish consumed in restaurants is Grade A. Grade B indicates good quality; Grade C indicates fairly good quality. Grade B and C products are most often canned or processed.

PURCHASING and STORING FISH and SHELLFISH

Determining Freshness

Because fish and shellfish are highly perishable, an inspection stamp does not necessarily ensure top quality. A few hours at the wrong temperature or a couple of days in the refrigerator can turn high-quality fish or shellfish into garbage. It is important that chefs be able to determine for themselves the freshness and quality of the fish and shellfish they purchase or use. Freshness should be checked before purchasing and again just before cooking.

Determined freshness by the following criteria:

- Smell - This is by far the easiest way to determine freshness. Fresh fish should have a slight sea smell or no odor at all. Any off-odors or ammonia odors are a sure sign of aged or improperly handled fish.

- Eyes - The eyes should be clear and full. Sunken eyes mean that the fish is drying out and is probably not fresh.

- Gills - The gills should be intact and bright red. Brown gills are a sign of age.

- Texture - Generally, the flesh of fresh fish should be firm. Mushy flesh or flesh that does not spring back when pressed with a finger is a sign of poor quality or age.

- Fins and scales - Fins and scales should be moist and full without excessive drying on the outer edges. Dry fins or scales are a sign of age; damaged fins or scales may be a sign of mishandling.

- Appearance - Fish cuts should be moist and glistening, without bruises or dark spots. Edges should not be brown or dry

- Movement - Shellfish should be purchased live and should show movement. Lobsters and other crustaceans should be active. Clam s, mussels and oysters that are partially opened should snap shut when tapped with a finger. (Exceptions are geoduck, razor and steamer clams whose siphons protrude, preventing the shell from closing completely.) Ones that do not close are dead and should not be used. Avoid mollusks with broken shells or heavy shells that might be filled with mud or sand.

Purchasing Fish and Shellfish

Fish are available from wholesalers in a variety of market forms:

- Whole or round - As caught, intact.

- Drawn-Viscera - (internal organs) are removed; most whole fish are purchased this way.

Seafood Freezing Terminology

- Fresh - The item is not and has never been frozen.

- Chilled - Now used by some in the industry to replace the more ambiguous "fresh"; indicates that the item was refrigerated, that is, held at 30°F to 34°F (- 1°C to 1 ° C).

- Flash-frozen - The item was quickly frozen on board the ship or at a processing plant within hours of being caught.

- Fresh-frozen - The item was quick-frozen while still fresh but not as quickly as flash- frozen.

- Frozen - The item was subjected to temperatures of 0°F (- 18°C) or lower to pre- serve its inherent quality.

- Glazed - A frozen product dipped in water; the ice forms a glaze that protects the item from freezer burn.

- Fancy - Code word for "previously frozen."

STORING FISH and SHELLFISH

The most important concern when storing fish and shellfish is temperature. All fresh fish should be stored at temperatures between 30°F and 34°F (- 1°C to 1°C). Fish stored in a refrigerator at 41°F (5°C) will have approximately half the shelf life of fish stored at 32°F (0°C).

Most fish are shipped on ice and should be stored on ice in the refrigerator as soon as possible after receipt. Whole fish should be layered directly in crushed or shaved ice in a perforated panso that the melted ice water drains away. If crushed or shaved ice is not available, cubed ice may be used provided it is put in plastic bags and gently placed on top of the fish to prevent bruising and denting. Fabricated and portioned fish may be wrapped in moisture-proof packaging before icing to prevent the ice and water from damaging the exposed flesh. Fish stored on ice should be drained and re-iced daily.

Fresh scallops, fish fillets that are purchased in plastic trays and oyster and clam meats should be set on or packed in ice. Do not let the scallops, fillets or meats come into direct contact with the ice.

Clams, mussels and oysters should be stored at 41°F (5°C), at high humidity and left in the boxes or net bags in which they were shipped. Under ideal conditions, shellfish can be kept alive for up to one week. Never store live shellfish in plastic bags and do not ice them.

If a saltwater tank is not available, live lobsters, crabs and other crustaceans should be kept in boxes with seaweed or damp newspaper to keep them moist. Most crustaceans circulate salt water over their gills; icing them or placing them in fresh water will kill them. Lobsters and crabs will live for several days under ideal conditions.

Like most frozen foods, frozen fish should be kept at temperatures of 0°F (-18°C) or colder. Colder temperatures greatly increase shelf life. Frozen fish should be thawed in the refrigerator; once thawed, they should be treated like fresh fish.

~Method for Preparing Live Lobsters for Sautéing~

A whole lobster may also be cut into smaller pieces for sautéing or other preparations.

- Using the point of a chef's knife, pierce the lobster's head.

- Cut off the claws and arms.

- Cut the tail into cross-sections.

- Split the head and thorax in half. The tomalley and coral (if present) can be removed and saved for further use. The head and legs may be added to the recipe for flavor, but there is very little meat in them and they are typically discarded.

- Crack the claws with a firm blow, using the back of a chef's knife.

~Procedure for Opening Clams~

Opening raw clams efficiently requires practice. Like all mollusks, clams should be cleaned under cold running water with a brush to remove all mud, silt and sand that may be stuck to their shells. A knife may be more easily inserted into a clam if the clam is washed and allowed to relax in the refrigerator for at least one hour before it is opened.

- Hold the clam firmly in a folded towel in the palm of your hand; the notch in the edge of the shell should be toward your thumb.

- With the fingers of the same hand, squeeze and pull the blade of the clam knife between the clamshells. Do not push on the knife handle with your other hand; you will not be able to control the knife if it slips and you can cut yourself.

- Pull the knife between the shells until it cuts the muscle. Twist the knife to pry the shells apart. Slide the knife tip along the top shell and cut through the muscle. Twist the top shell, breaking it free at the hinge; discard it.

- Use the knife tip to release the clam from the bottom shell.

~Procedure for Opening Oysters~

- Clean the oyster by brushing it under running water.

- Hold the cleaned oyster firmly in a folded towel in the palm of your hand. Insert the tip of an oyster knife in the hinge and use a twisting motion to pop the hinge apart. Do not use too much forward pressure on the knife; it can slip and you could stab yourself

- Slide the knife along the top of the shell to release the oyster from the shell. Discard the top shell.

- Use the knife tip to release the oyster from the bottom shell.

- Fresh raw oysters on the half shell with seaweed garnish.

Mussels are not normally eaten raw. Before cooking, a clump of dark threads called the beard must be removed. Because this could kill the mussel, cleaning and de-bearding must be clone as close to cooking time as possible.

- Clean the mussel with a brush under cold running water to remove sand and grit.

- Pull the beard away from the mussel with your fingers or a small pair of pliers.

A whole lobster can be cooked by plunging it into boiling water or court bouillon. If the lobster is to be broiled, it must be split lengthwise before cooking.

- Place the live lobster on its back on a cutting board and pierce its head with the point of a chef's knife.

- Then, in one smooth stroke, bring the knife down and cut through the body and tail without splitting it completely in half.

- Use your hands to crack the lobsters back so that it lies flat. Crack the claws with the back of a chef's knife.

- Cut through the tail and curl each half of the tail to the side. Remove and discard the stomach. The tomalley (the olive-green liver) and, if present, the coral (the roe) can be removed and saved for a sauce or other preparation

Various Cooking Methods. Fish and shellfish can be prepared by the dry-heat cooking methods of broiling and grilling, roasting (baking ), sautéing, pan-frying and deep-frying , as well as the moist-heat cooking methods of steaming, poaching and simmering.

Determining Doneness

Unlike most meats and poultry, nearly all fish and shellfish are inherently tender and should be cooked just until done. Indeed, overcooking is the most common mistake made when preparing fish and shellfish. The Canadian Department of Fisheries recommends that all fish be cooked 10 minutes for every inch (2.5 centimeters) of thickness, regardless of cooking method. Although this may be a good general policy, variables such as the type and the form of fish and the exact cooking method used suggest that one or more of the following methods of determining doneness are more appropriate for professional food service operations:

- Translucent flesh becomes opaque - The raw flesh of most fish and shellfish appears somewhat translucent. As the proteins coagulate during cooking, the flesh becomes opaque.

- Flesh becomes firm - The flesh of most fish and shellfish firms as it cooks. Doneness can be tested by judging the resistance of the flesh when pressed with a finger. Raw or undercooked fish or shellfish will be mushy and soft. As it cooks, the flesh offers more resistance and springs back quickly.

- Flesh separates from the bones easily - The flesh of raw fish remains firmly attached to the bones. As the fish cooks, the flesh and bones separate easily.

- Flesh begins to flake - Fish flesh consists of short muscle fibers separated by thin connective tissue. As the fish cooks, the connective tissue breaks down and the groups of muscle fibers begin to flake, that is, separate from one another. Fish is done when the flesh begins to flake. If the flesh flakes easily, the fish will be overdone and dry.

Remember, fish and shellfish are subject to carryover cooking. Because they cook quickly and at low temperatures, it is better to undercook fish and shell- fish and allow carryover cooking or residual heat to finish the cooking process.