2.43: Case: Community Gardens

- Page ID

- 21025

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Howard Rosing is the Executive Director of the Steans Center at DePaul University and teaches courses on urban food systems in the Department of Geography and the MA in Sustainable Urban Development. Dr. Rosing is a cultural anthropologist who has authored numerous publications on urban and community food systems including the co-authored book Chicago: A Food Biography. He holds a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Binghamton University.

Ben Helphand is the Executive Director of NeighborSpace, a nonprofit urban land trust dedicated to preserving and sustaining community managed open spaces in Chicago. NeighborSpace owns a large network of growing spaces across the City so that community groups can focus on gardening and community building. He holds a BA from Wesleyan University and a MA in the History of Religion from the University of Chicago.

Amy DeLorenzo is an Extension Educator at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign where she works on developing the pipeline of agricultural talent in the state of Illinois and to create partnerships with food and beverage companies in the Chicagoland area. She holds a BA in International/Global Studies from DePaul University and a MA in Geography from the University of Guelph.

Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Explain how urban community gardens address social and economic challenges to food access while building greater community cohesion.

- Examine the importance of community gardens in supporting food security and food justice.

- Compare the case of community gardens in Chicago with a case in their own city or town.

- Describe the role of community gardens in improving the health and wellbeing of urban communities.

Introduction

Building sustainable food-producing communities requires a complex set of skills and talents that go far beyond technical knowledge and science. This text offers a multifaceted perspective on the practice, debates on, and process of producing and sustaining community gardens in North American cities. Drawing from research on community gardens across Chicago, the study highlights how community gardens offer an important mechanism for creating resilient, socially cohesive communities that can respond to social, economic, and environmental challenges. The study sheds light on gardeners as neighborhood assets in urban sectors where access to fresh food is challenged by historical patterns of racial segregation and social exclusion. Given insufficient availability and/or increasing cost for healthy fresh food for large segments of Chicago’s population, researching how people organize to cultivate fresh food, how much food they produce, how and where their yields are distributed, the nutritional value of their crops, and the meaning of gardens for gardeners, offers a holistic understanding of what it takes to build sustainable community food systems in large cities.

Chicago is an ideal city to study community gardens in the 21st century. The city’s historical motto, Urbs in Horto (“city in a garden”), symbolizes longstanding horticultural practices among residents across neighborhoods and social classes.[1] Notwithstanding the city’s rich garden history, for much of Chicago’s recent past, community gardening has been primarily a grassroots effort with little in terms of municipal government investment. Starting during the 1990s, Chicago created the job training program GreenCorps, which provided resources to community gardens, but the effort that was cut by the subsequent mayor. Until 2011, there was no legal land-use code for urban agriculture in Chicago, meaning community gardeners would in many cases be doing so outside zoning laws governing land use. This policy, or lack thereof, had particular impact on neighborhoods that lacked proximity to fresh food resources. For decades, Chicago’s racist urban planning practices, combined with discriminatory mortgage lending and real estate development, resulted in neighborhood divestment and property devaluation on the south and west sides of the city. By the 1990s, the outcome was a shortage of supermarket retailers in economically distressed neighborhoods, largely populated by Black and Latinx residents.[2] Nonprofit and grassroots efforts to organize community gardens in these neighborhoods were thus partly a neighborhood resilience strategy in response to limited access to fresh food, and partly about community building and self-determination.

The label “food desert,” or what some authors describe as “supermarket redlinings,”[3] was ascribed to many southside and westside Chicago neighborhoods by the early 2000s, due to a lack of full-service supermarkets.[4] The label misrepresented decades of growth of community gardeners, who offered food assets in their neighborhoods. Indeed, the vast majority of the 260 community gardens researched in this study were located on the south and west sides of Chicago. McClintock describes this urban growing movement as having an “emancipatory role,” a type of active resistance through “ecological stewardship with social justice.”[5] Rather than constructing community gardeners of color as passive victims of racial and economic marginalization, resulting in significant health disparities, community gardeners in segregated cities like Chicago are better understood through their own agency and diverse ways and reasons for producing food. This study emerged out of an effort to highlight the importance of community gardens, especially for Chicago neighborhoods with limited access to fresh food.

There is no one metric by which to evaluate what makes a community garden successful. Laura Lawson in City Bountiful states that the dominant narrative tends to link community gardens to community food security, but given the numerous reasons people state as to why they garden, food security should not be the only measure of success.[6] The enormous harvest and nutritional yield from gardens in Chicago dispels a popularly held notion that community gardens do not produce significant amounts of food. Yet community gardeners have diverse motivations for organizing collectively to produce food from year to year. Understanding these motivations requires deeper inquiry into what people think about theirgardens: that is, why gardens matter to gardeners. While this study illustrates that community gardens “count” both at neighborhood and city levels in respect to building greater food security, there are numerous other reasons for community gardens, not the least of which is creating ecologically sustainable and aesthetically pleasing spaces that build pride in community and positive relationships with neighbors. Documenting the values attached to community gardens in urban spaces, especially in those spaces marked by racially motivated divestment, helps to identify ways that cities can invest in neighborhood-based food production as a means for building more equitable urban food systems.

Research Process

One of the first tasks in researching community gardens in a city as large as Chicago is to define what is meant by the term “community garden.” The definition for this study was developed by the organization NeighborSpace, a nonprofit urban land trust charged with protecting community-organized and managed growing spaces across Chicago.[7] The organization takes on land ownership and assists gardeners with insurance, access to water, and other resources. Gardens on land protected by NeighborSpace are no longer susceptible to removal as a result of, for example, more powerful, capital-intensive development interests. Equipped with a definition of community gardens, researchers for this study visited 260 gardens across Chicago, of which 208 fit the definition during the 2013 growing season.

Researchers defined community gardens in Chicago as growing sites that presented both internal and external community-fostering properties. Internal community fostering properties refer to the development of social ties among people who work together at the garden. External properties refer to the potential impact that the garden has on the outside environment in the form of neighborhood improvement, beautification, food access, violence prevention, increase in property values, youth development, health benefits, and more. The study did not include sites where the majority of produce was sold, where there were paid employees, where the site was used exclusively for social service and/or educational programming, and/or where the site was in a private, for-profit housing establishment exclusive to those residents and inaccessible to the public.

Fieldwork for the study consisted of seven distinct components: (a) identifying community gardens; (b) counting square footage of food crops grown in the gardens during spring, summer, and fall; (c) sampling 29 sites that broadly represented a cross-section of Chicago’s community gardens; (d) sampling seven gardens representing seven distinct neighborhoods and diverse growing conditions where gardeners agreed to weigh their harvest; (e) measuring the replacement value of foods produced in the gardens through documentation at retail food outlets; (f) interviewing gardeners about their garden’s history, organization, distribution, and use of food; and (g) calculating nutritional values of the foods produced.

At all 260 community gardens initially visited, detailed information was recorded about the garden and its food crops, including the total size of garden properties, the number of plots, water sources, evidence of support organizations, and other data. Researchers recorded the total area (square footage) of each crop. These tabulations, along with the weight of crops at the seven selected community gardens, enabled researchers to estimate the yield (pounds per square foot) of vegetables and fruits within the areas under production. In order to provide a basis for estimating the productivity by weight, dollar value, servings, and nutritional scores, researchers arranged with gardeners and support organizations at the seven gardens to weigh their harvest. These gardens were in different neighborhoods with diverse soils, growing conditions, gardeners, and institutional affiliations, and constituted a fairly representative cross-section of Chicago’s community gardens. Gardeners weighed their harvest by crop and researchers employed the results of the tallies to estimate the average productivity of different crops and to arrive at yield estimates for the production of all community gardens surveyed.[8] To calculate replacement value or cost of these foods, researchers visited twelve retail outlets, representing a wide range of grocers (luxury, mid-priced, and discount) and farmers markets in different Chicago neighborhoods. At each of the outlets, prices were recorded for the various vegetables, fruit, and herbs grown in the gardens.

To understand garden distribution processes and the underlying meanings of community gardens for gardeners, researchers interviewed 53 gardeners at 32 gardens about garden history, organization, and especially distribution and use of the food. The interviews helped explain what people do with food grown in the gardens, how community gardens affect the community, and the role of gardens in community-building, youth development, food access, beautification, and the nutritional well-being of residents.

Food Production in Chicago Community Gardens

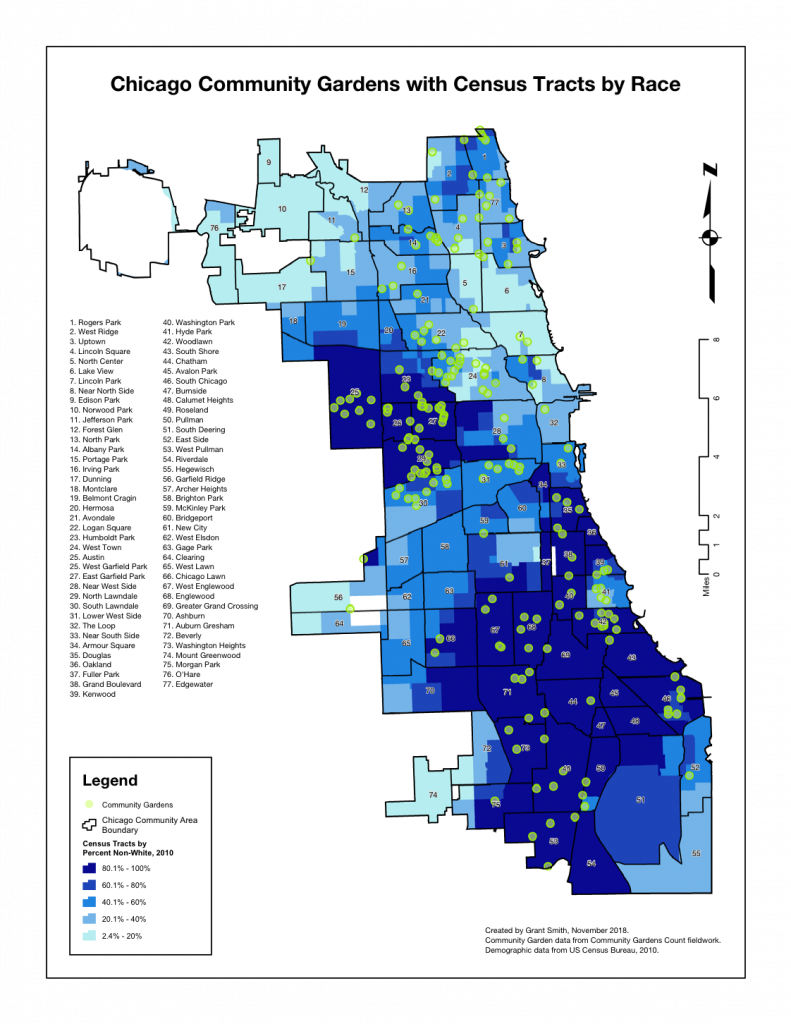

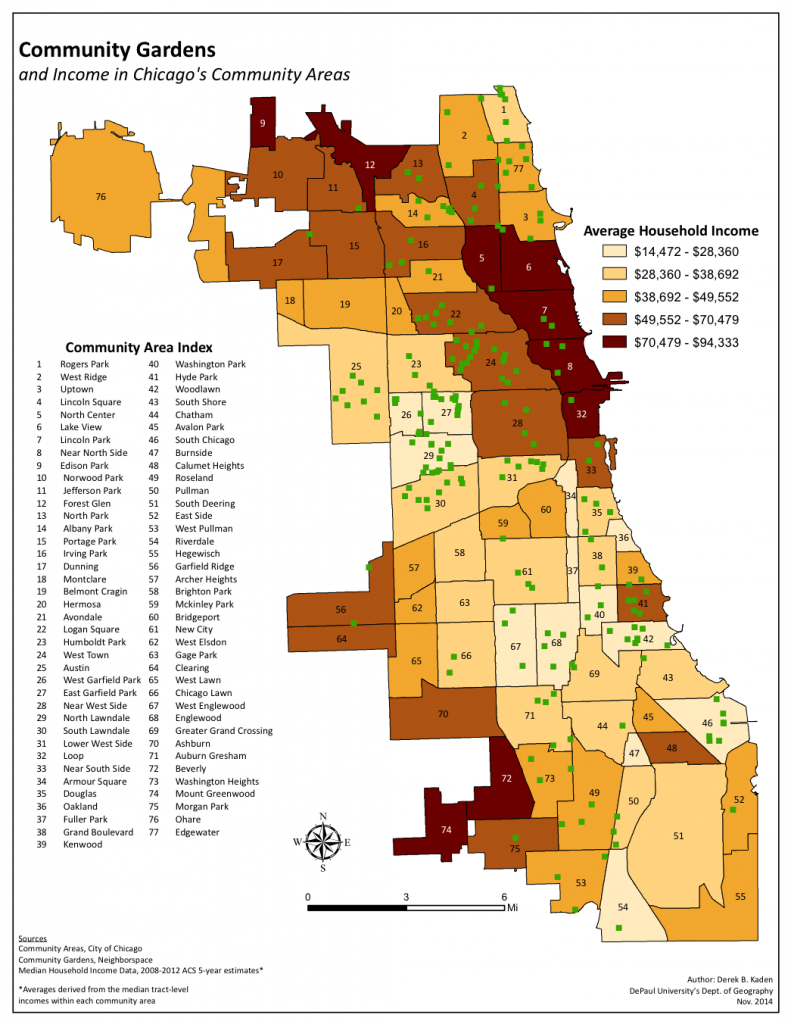

The study estimated that 517,157 pounds of food was produced on 43.56 acres of community gardens during the 2013 Chicago growing season. Most of this food was produced in low- to lower-middle–income neighborhoods. Nutrient rich fruits and vegetables went directly into gardeners’ households and were in many cases redistributed through neighborhood social networks to other households multiplying the impact on food access for Chicagoans who might otherwise not regularly have access to fresh, healthy foods. As can be seen in Figure 1, the vast majority of community gardens are clustered in non-white areas of Chicago; as noted in Figure 2, these are also the lowest-income areas of the city.

Among the many crops produced by Chicago community gardens, 20 stood out as yielding the highest poundage. (See Table 1.) Mapping these 20 crops by Chicago’s 77 community areas spatially revealed the cultural and economic importance of crops across neighborhoods with diverse demographics. For example, more than 5,000 pounds of collard greens were produced in the southside neighborhood of Washington Heights, a neighborhood populated by more than 95 percent Black or African American residents, and most of which was classified in research studies as a food desert.[9] Community gardens thus also provided neighborhood access to culturally important, nutrient-rich food, the economic value of which can be seen in Table 2.

[table id=1 /]

[table id=2 /]

Food Distribution, Youth Engagement, and Community Building

Distribution of food from Chicago’s community gardens is a complex, informal, and often ad hoc neighborhood provisioning process described by gardeners through interviews. For example, gardeners described how many gardens are openly accessible to neighbors, as one interviewee explained: “The neighbors take some, ain’t nobody sellin’ it, somebody might come by and take some, but most people come by and do it like they would from the store—put it in a box.” Interviewees were asked whether they distribute portions of their yield to friends and neighbors. Most described that they would give surplus produce away to family, friends, and others who they knew needed it. Many mentioned harvest days or cook-out days, when neighborhood residents would assist with the harvest and/or cook and eat together. Permanent or impromptu meeting spaces with furniture and cooking resources were often visible at gardens, reflecting how the sites offered neighborhood social gathering points that encouraged community building. Indeed, as one gardener described, some gardens were highly accessible to neighbors: “So, for the most part, we’re eating what we grow. And if we’re not eating what we grow, people who walk by and pick it are eating what we grow.” Other gardeners emphasized the ethos of food sharing at the gardens: “We gave food to people, anybody we see. Cause we couldn’t use all that. We couldn’t use all the food!”

Community gardens in Chicago were also important for encouraging positive youth development. As one interviewee noted, “I think we really want kids to eat healthy. I mean we want families to eat healthy, but obviously starting with children. You know, teaching them why you’re supposed to eat fruits and vegetables. I think we technically live in a food desert, where there is not a lot of access to fresh produce, so wanting kids to have that access, but also just wanting kids to know like, this is how broccoli grows, break it off and eat it.” Other sentiments by gardeners highlighted how gardens provide important educational resources not offered in formal schooling. Youth learned about communal production, food sharing, and the origins of food. As another gardener noted, “We also have kids who just—they’ll take a pot of greens and take it home with them. And kids really, really love it because I have this one kid who, two months ago, he was like, ‘Hey, are we gonna grow those things that are orange and long?’ I was like, ‘A carrot.’ He was like, ‘Yeah, a carrot. Are we gonna grow those?’”

In general, gardeners explained how community gardens offered a safe space for local youth to engage with one another and intergenerationally to learn gardening and civic skills and the importance of mutual aid and care within neighborhoods. “I have a lot of neighbors who have kids who help me garden,” explained one gardener. “they help me plant the seeds, they help me water. When I go out of town, I ask them to water, they love it. So, yeah, it’s reaching a lot of, a lot of families.”

Nutritional Impact from Chicago Community Gardens

The far-reaching nature of community gardens within many Chicago neighborhoods, especially for households that lack proximity to full-service grocery stores, illustrates the relational process of communal food production. The informal social processes described above have an impact on the physical well-being of residents through nutritional intake. Using the estimated production yields, researchers calculated the number of servings of specific foods per garden, as well as related nutritional data such as fiber content (See Tables 3 and 4). For example, gardeners produced an estimated 588,516 servings of collard greens, averaging 6,848 servings per garden, and delivering some 905,410 grams of fiber. Along with the significant health benefits of such leafy green vegetables, these findings provide evidence for advocacy, planning and policymaking in support of gardens, especially for neighborhoods marginalized by the retail food sector.

[table id=3 /]

Data Analysis by Angela Odoms-Young, University of Illinois at Chicago

[table id=4 /]

Data Analysis by Angela Odoms-Young, University of Illinois at Chicago

The Value ofCommunity Gardens in Cities

Research on the yield from Chicago community gardens, combined with gardeners’ descriptions of how food is distributed across neighborhoods, counters popular perceptions of community gardens as spaces that do not produce significant amounts of food. The study shows that Chicago community gardens are essential public health assets for providing highly nutritious foods that are often not otherwise locally available. The estimated 259 tons of food produced by Chicago community gardens during the 2013 growing season had an estimated value of US$1,665,698, demonstrating the economic value of communal food production. Some gardens were so successful that they had explicit goals of being community food distribution hubs, creating direct supply chains to food pantries or through large distribution events and community meals.

No matter the manner in which food is distributed from gardens, the process of growing, harvesting, and distributing food nurtures positive relations among neighbors and especially for youth. Recurrent themes among interviewees included “feeding” the community spiritually or mentally, and that gardens provide a beautiful space of respite in a hectic, busy city. Gardeners described gardens as “a community backyard,” a place for children to play safely, and a point of pride for their neighborhood. In some neighborhoods, gardens act as a bridge between newcomers to an area and long-time residents, who come together with a common vision of a more beautiful neighborhood, reducing potential for conflict, and further emphasizing why community gardens are important assets that should not be overlooked by policymakers and planners.

Urban policymakers would do well to recognize the intrinsic value of gardens in feeding and healing communities and creating safe, educational spaces for children and adults alike. In Chicago, the study determined that 20 percent of all Chicagoans (547,360) live within two blocks (1/4 mile) of a community garden. Extrinsically, these gardens hold value in that they feed both the gardeners themselves and residents across neighborhoods. For some Chicago neighborhoods, the gardens are the only local place where people can have access to fresh, culturally appropriate produce. While gardens cannot be the primary solution for food insecure neighborhoods, they should be recognized as an important piece of a larger process of systematically addressing disparities in urban food access.

There are a variety of ways that cities can support community garden development. Interviewees noted the necessity of gaining access to land in proximity to water sources, such as water lines or fire hydrants, that are permissible to use by gardens. In addition to land and water, access to soil is critical, since creating food-producing gardens on what are often toxic and/or paved spaces requires building raised beds. To keep people safe from harmful contaminants, purchasing high-quality soil is an expense often difficult for gardens to maintain. Policies can be implemented to support composting and environmental remediation of publicly owned vacant land suitable for gardening. In sum, gardeners recommended easing financial burden and removing barriers to entry for creating and maintaining gardens.

Chicago’s community gardens were described by gardeners as places where people “are seen as equals,” where there is “no hierarchy” between new and long-term residents. Investing in these spaces is an investment in promoting peace, and can be weighed against the cost of policing cities. Community gardens support self-governance and self-determination, neighborhood beautification, and caring for neighbors. Building sustainable food-producing communities thus requires an approach that goes far beyond applying technical knowledge. This study highlights how community gardens offer an important mechanism for creating resilient, socially cohesive communities that can respond to social, economic, and environmental challenges. As neighborhood assets in racially segregated cities like Chicago, gardens offer a community response to insufficient availability and/or increasing cost of fresh food in a changing global economy and environment. Reducing the costs of gardening, and making community gardening as easy as possible, is thus a valuable investment in public health. Prioritizing community gardens in urban planning, policymaking, and development ensures that these spaces count and will lead to the development of more socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable food systems that are less reliant on importing food to feed cities.

Discussion Q uestions

- Why are community gardens important for public health in North American cities and towns?

- Should governments invest tax dollars in community gardens? Why or why not?

- In what ways can community gardens respond to racial injustice?

- How does your city or town support community food production? How can you get involved?

Exercises

Visit a local community garden

This exercise should take about four hours of time.

Visit an existing community garden in your city or town. If possible, choose a garden close to where you live. Answer the following questions about the garden in a notebook, laptop, or tablet:

What did you see when you visited the garden (physical, social environment)?

Does the garden seem like it is well taken care of?

Do you get a sense that the garden is an active growing space? Why?

Is there something that makes this garden distinct from others?

Did you talk to anyone at the garden? What did they say?

Describe the garden in as much detail as possible. Your answer should be a minimum of 500 words, but there is no maximum limit.

Using your phone or a camera, make an audio and/or video recording of yourself while visiting the garden. The recording should describe the garden in as much detail as possible, but should be no longer than five minutes in length. In particular, identify any symbols of how community members are working together to grow food (communal growing) and ways in which the garden seems to be designed to build or support community (tables, barbecue, etc.). Make sure to avoid filming people’s faces, and include the location and name of the garden in your recording.

Submit your notes and recording to a shared drive where students can review each other’s submissions.

Note to instructors: Following review of all the submissions, prepare for class discussion by determining what patterns or themes you see occurring across the different community gardens visited by students in your class. What can these patterns tell you about the culture and practice of community gardening in your town or city?

Map community gardens in your town or cit y

Using Google maps or another mapping tool, work with your class to begin mapping community gardens in your neighborhood, town, or city. For an example of what you can map, see the Chicago Urban Agriculture Mapping Project(CUAMP), which was developed in conjunction with the Community Gardens Count study. Pay special attention to the Advanced Search features of CUAMP and explore the types of garden features that can be added to the public map. Decide as a class or in small groups what you would like your map to look like and contain. Make sure to visit the gardens that you map to ensure that they are still there.

As you add gardens to the map, discuss with the class what the geography of community gardens says about local food production in your town or city. How does the location of gardens and what they contain relate to the demographics in your region? How does racism and class play a role in where and how community gardens operate?

Engage in service-learning with a community garden

Service-learning can be defined in several ways, but in general it involves intentionally integrating relevant and meaningful service with the community with academic and civic learning. While it involves students in service as a learning strategy, service-learning is not synonymous with community service or volunteering.

For this exercise, students will be assigned to one of several pre-arranged community gardens, where they should serve a minimum of 20 hours of service, spread out over the school semester. Students should maintain a journal of their weekly experiences. A set of guided questions should be developed by the instructor, linking student observations and reflections to course readings, guest speakers, and learning resources. During several class sessions, students and the instructor should reflect on their experiences and discuss the value of this type of learning, both for students and for communities.

Additional Resources

Anti-racism in community food growing: Signposting: An online informational resource from the London-based organization, Capital Growth.

Strengthening Equity & Inclusion in Garden Education: An online informational resource from the School Garden Support Organization.

Inclusive Community Gardens: A downloadable resource from the City of Vancouver.

References

Block, Daniel, Noel Chávez and Judy Birgen. “Finding food in Chicago and the suburbs: the report of the northeastern Illinois community food security assessment report to the public.” 2008.

Eisenhauer, Elizabeth. 2001. “In poor health: Supermarket redlining and urban nutrition.” GeoJournal 53: 125–133.

Gallagher, Mari. “Examining the impact of food deserts on public health in Chicago.” 2006.

Lawson, Laura J. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2005.

Maloney, Cathy Jean. Chicago Gardens: The Early History. University of Chicago Press, 2008.

McClintock, Nathan. “From industrial garden to food desert: Unearthing the root structure of urban agriculture in Oakland, California.” 2008.

Vitiello, Dominic and Michael Nairn. “Community gardening in Philadelphia: 2008 harvest Report.” 2009.

- Maloney 2008. ↵

- Block, Chávez & Birgen 2008; Gallagher 2006. ↵

- Eisenhauer 2001. ↵

- Gallagher 2006. ↵

- McClintock 2008, 6-7. ↵

- Lawson 2005. ↵

- The project was built on partnership between NeighborSpace, DePaul University, University of Illinois at Chicago, University of Pennsylvania, Angelic Organic Learning Center and E.A.T. This research was made possible by a generous grant from the Consortium to Lower Obesity in Chicago Children and from a charitable donation made by the Walton Family Foundation. ↵

- Vitiello & Nairn 2009. ↵

- Gallagher 2006. ↵