1.7: Case- Food in Sāmoa

- Page ID

- 20989

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Outcomes

After reading and discussing this text, students should be able to:

- Identify common contemporary dietary crises in Samoa and draw connections to food history in the region.

- Articulate the central role of food in Samoan culture (and other Indigenous Oceanian cultures, more broadly).

- Describe the complications of looking to food pasts to solve food problems in the present.

Introduction

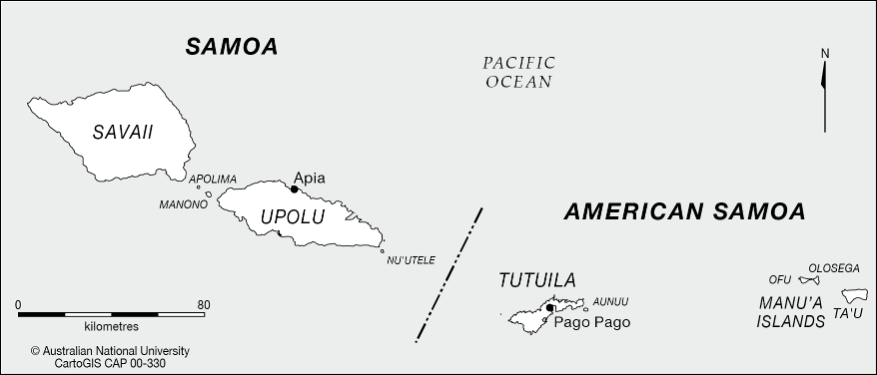

Like many island nations and territories in Oceania, the two polities of Sāmoa (the Independent State of Sāmoa and the U.S. territory of American Samoa) are undergoing a serious health crisis. Problematic conditions linked to dietary habits are resulting in increased hospitalizations, surgeries, and even deaths. These conditions include type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and obesity, among others.

During my time conducting food research throughout the archipelago, which included years of participant observation, I noticed that imported processed foods were heavily featured in contemporary daily diets. While living with a host family on the island of Manono in the Independent State of Sāmoa, not a day went by that we didn’t eat hot dogs, instant ramen, white bread, or canned corned beef, which were generally accompanied by soda or other sugary drinks and juices. We also frequently ate ancestral foods, or foods produced, procured, and eaten long before outsider arrival in Sāmoa. These included foods like baked taro, breadfruit, and yams, or starchy varieties of bananas stewed in coconut cream, along with locally caught fish or locally raised chickens and pigs, and sometimes served with a glass of vai tīpolo, which is a juice derived from a local citrus fruit.

In either case, when we ate, we ate a lot. My host family was culturally obligated to take care of me, as a guest in their home, and this primarily centered on providing me with ample amounts of food. I once remarked to a friend in my village that I could barely finish my daily meals, to which he replied, “Good. That means your family is taking care of you.” As a Samoan, he knew that my host family would be highly regarded by their neighbors for their ability to host and to provide. Even without guests in the home, though, Samoan families still tend to eat large meals for similar reasons, because providing for one’s children or parents is also a sign of familial respect, care, and love. This provision primarily comes in the form of food. Ensuring that one’s family has plenty to eat is an assurance that one is of service and utility to their family, and therefore in keeping with the Faʻasāmoa—the Samoan way of life.

Though my research was more concerned with charting changes over time in Samoan foodways than with contemporary dietary disease, the issue of health and wellness constantly came up when discussing my work with others. Whether talking with Samoan scholars at different universities and archival centers, or with my host family or my friends in the village, I tended to hear the same sentiment shared over and over again: If only Samoans ate the foods they used toeat, then dietary disease would go away entirely. However, the uncomfortable truth that some acknowledged and many avoided remained: Newer, imported foods are just too tasty, too ingrained into Samoan diets, and too deeply embedded into Samoan culture itself to cut out entirely.

This chapter presents a historical overview of Samoan food and food culture, introducing readers to the roots of Sāmoa’s contemporary health crisis. In so doing, it offers a window into a problem that is not unique to Sāmoa alone. However, while dietary disease is on the rise around the world, the unique place of food in many Indigenous Oceanian cultures as a means of conveying notions of respect, love, and wealth means that many Indigenous Oceanian peoples are eating more and more imported processed foods. In what follows, therefore, I also show how these new and imported foods are entangled with deeper notions of Samoan taste, making it all the more difficult to eliminate them from Samoan diets. Finally, I ask readers to consider whether a “back to the future” approach—that is, an approach in which Samoans return to eating ancestral foods completely—is really feasible.

Food in Sāmoa’s Deep Past

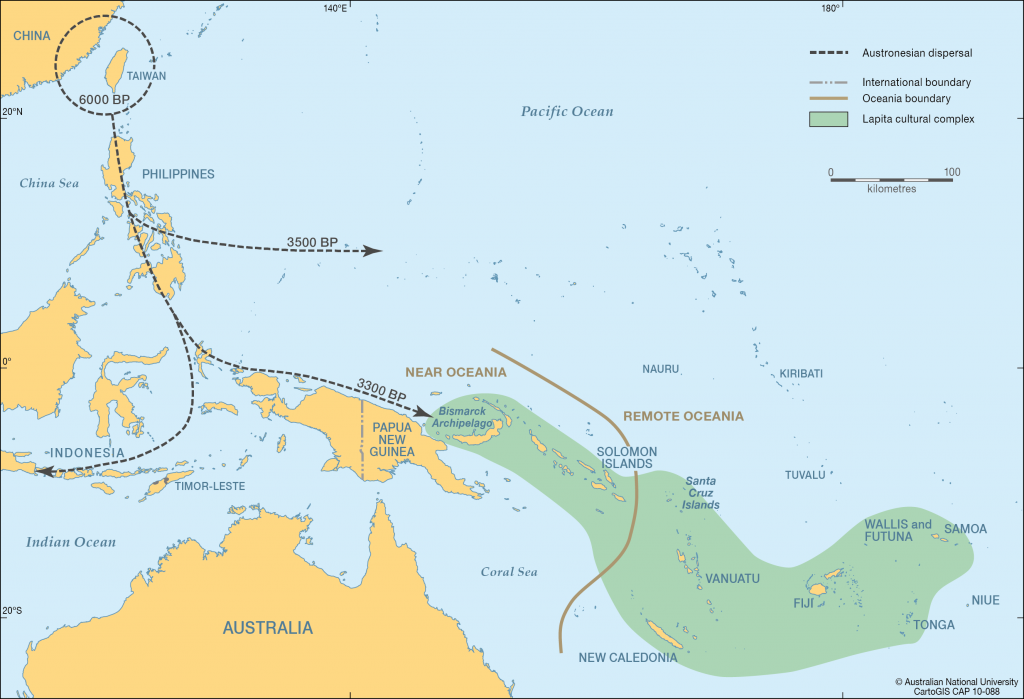

When the Lapita peoples arrived in the Samoan archipelago around 3,500 years ago, they came prepared. Having long since mastered the domestication of animals like dogs, chickens, and pigs, the cultivation of crops like coconut, taro, and breadfruit, and the development of cooking techniques like the earth oven, Lapita peoples successfully colonized the Samoan archipelago as well as other island groups in Oceania.

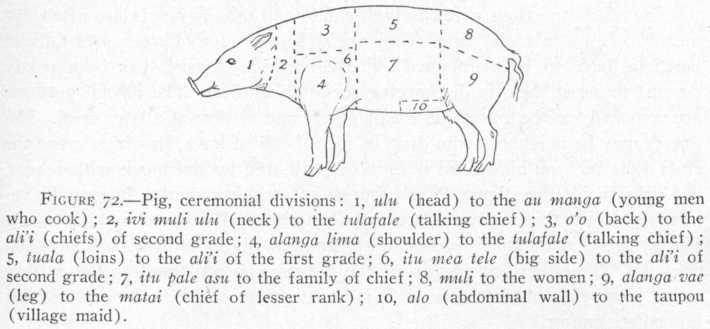

As a distinct Samoan language and culture developed out of the first Lapita peoples, it eventually became predicated upon a matai, or chief, system. Daily life was paced by the will of matai who were obligated to look after the villages over which they held political influence. This meant, among other things, regulating the production and procurement of food. Matai delegated land for cultivation, organized and regulated the procurement of fish and shellfish, and deemed when it was appropriate to kill and prepare more specialized foods, such as chickens and pigs. In turn, non-matai village members were obligated to pay food tributes to their matai during important ceremonies and rituals, providing matai with prized food items like the heads of fish or loins of a pig.

As Sāmoa’s population grew, Samoan society and the matai system became even more stratified, and several different rankings developed. Some of these highly stratified rankings could be seen in food production, procurement, preparation, and service. For example, young men without matai titles were expected to carry out most of the day-to-day production and procurement of food, such as minding plantations and catching fish. They were also the primary cooks, as Samoan cooking with an ʻumu, or earth oven, is considered a laborious and dangerous job. Though some women held matai titles—and very high-ranking titles, at that—the vast majority of matai were men. As a result, women were primarily expected to raise families and maintain the cleanliness of villages and homes, although they also had specific food duties, such as procuring shellfish from shallow coastal waters. Age roles developed, too. Generally speaking, younger men and women were responsible for more laborious tasks while older people, titled or not, were taken care of by their children and grandchildren.

At regular intervals, peoples of all ranks came together for ceremonies and celebrations to mark significant moments in time, such as weddings, funerals, birthdays, and victories in war, and large feasting always accompanied these events. The strength and dignity of a village was often derived from their ability to host traveling parties from other villages. Likewise, the strength and dignity of villages represented by traveling parties, or guests, was often derived from their ability to present food gifts and tributes to their hosts in return. In this sense, food was integral in establishing relationships between peoples and groups.

As Samoan food culture developed, so too did Samoan tastes. Many oral traditions speak of lolo, or rich, fatty foods as being most prized. This is perhaps due to the fact that so much of Samoan food consisted of coconut cream, which is a rich, fatty substance that was often cooked with and/or served with baked taro, breadfruit, fish, and other staple foods. In fact, some of the elders I spoke with during my research told me that this is why the heads of fish or the loins of a pig are gifted to the highest-ranking matai—because these pieces contain the most lolo flavor.

This early period of Samoan food history was marked by intense labor. It is not easy to climb a coconut tree or to pull taro up from the root, not to mention moving the rocks necessary to form an ʻumu. Even a seemingly ‘easy’ task like picking shellfish off coastal rocks and coral still takes a significant amount of energy. This work—the work of food—regulated Samoan society for generations, but it also meant that peoples burned a significant number of calories to maintain steady diets.

Food in Sāmoa’s Recent Past

Europeans first sighted Sāmoa in the mid-18th century, but contact between Europeans and Samoans was very limited until 1830, when missionaries from England began working to convert Samoans to Christianity. Around this same time, a global whaling industry boomed, which brought several pālagi, or non-Samoans, to Samoan shores, to refuel their ships, trade their cargo, or to settle permanently and profit from Sāmoa’s burgeoning economy. As the Samoan economy boomed, European and American colonial interests peaked as colonial agents sought to profit from industries like whaling and copra. By 1900, the Samoan archipelago was split into two halves, and without much voice given to Samoans themselves.

Though this history of colonialism goes much deeper, it is important to note here that these early pālagi brought with them something that would change Samoan food forever—canned goods. These included canned vegetables, fish (especially salmon), and beef, including the highly prized pīsupo, or corned beef, so named because in its early canned form it resembled cans of pea soup. Given their scarcity, and especially their lolo flavor, canned fish and meats became especially highly prized items in Samoan society. Where once a high-ranking matai might have expected a certain cut of pig or piece of fish as a food tribute from their village or a traveling party, they eventually grew to expect imported pālagi foods. Still, throughout the nineteenth century, limited supply of canned goods, a small overall population, and the fact that most Samoans remained largely within ancestral subsistence economies, all prevented an exponential growth of Sāmoa’s pālagi food presence.

By the mid-20th century, however, a combination of factors changed this. Catastrophic natural disasters brought in food aid from countries like New Zealand, Australia, and the United States, including flour, yeast, rice, and sugar in great supply. This influx gave way to new foods like pani popo (literally “coconut bread”), or buns baked in coconut cream, and koko alaisa (literally “cocoa rice”), or rice cooked in hot cocoa. In addition, the world wars in the early-to-mid-20th century meant more people, industry, and cash in Sāmoa’s economy, giving more Samoans exposure and access to pālagi foods. As with many island groups in Oceania, food items like SPAM became a bigger part of daily diets, and with more Samoans able to afford more pālagi foods, Samoan tables began looking more and more pālagi by the minute, while also retaining many ancestral foods like taro, coconut, and breadfruit. While restaurants, bars, bakeries, dairies, and grocery stores had existed in Sāmoa since the mid-nineteenth century, they rapidly expanded through the mid- and late-20th century. Before long, both Samoan polities had several eateries and groceries selling ultra-processed foods. For example, the Independent State of Sāmoa boasts its own McDonald’s fast food restaurant, while the less populated American Sāmoa claims two, along with other fast food establishments like Carl’s Jr. and Pizza Hut.

Food in Sāmoa’s Present and Future

While foods changed, Samoan cultural values surrounding food persisted. This is not to say that Samoan culture remained static, as it continued to change during the 20th century, just as it had prior to European arrival in the islands. Rather, the ties between food, gifting, ceremony, respect, and provision remained a central tenant of the Faʻasāmoa. As such, Samoans continued to place incredible value on providing prized lolo foods to family, friends, matai, and any other peoples with whom they wished to sustain positive relationships. At the same time, within families, providing one another with plenty to eat remained a crucial way to communicate love, respect, and care. Consider, too, that with ease of access comes a lack of activity. Where foods were once difficult to cultivate, catch, and cook, they are now readily available on grocery shelves, and with the transition of many from subsistence to sedentary lifestyles and work, less activity means fewer calories burned. Some food scholars have labeled this kind of change in food choices and activity levels as the “nutrition transition.”

We also need to consider the interplay of food and colonialism. While this subject is too complex to go into here, it should be noted that power dynamics between smaller island nations like Sāmoa and larger nations like New Zealand, Australia, and the United States often involve some degree of hegemony. In regard to food, this can mean the exportation of unhealthy foods into Sāmoa without correlating funding for the medical problems that inevitably arise from eating such foods. For example, the Independent State of Sāmoa tried to implement various bans on imports, including a recent ban on turkey tails, but they received pushback from wealthier nations who threatened to restrict their induction into the World Trade Organization, not to mention significant local uproar from Samoan people who love turkey tails’ lolo flavor. With limited political recourse or external public health support, and widespread local demand for imported foods, both Samoan polities find themselves struggling to combat dietary disease. Craig Santos Perez, a CHamoru scholar and poet, calls this kind of power dynamic “gastrocolonialism,” which he broadly defines as “structural force-feeding.” According to Perez, gastrocolonialism not only erodes food cultural knowledge and increases dependency on imported foods, but it also leads to chronic diseases linked to poor diet. This is certainly true of Sāmoa.

In a recent documentary (which forms the foundation for an assignment at the end of this chapter), a Samoan doctor called type 2 diabetes a “tsunami in the Pacific.” Indeed, several recent studies show that both Samoan polities and several other Oceanian territories and nations have some of the highest per capita cases of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and other diet-related conditions in the world. Later in the documentary, the same doctor states that when he was young, he ate mostly ancestral foods, whereas Samoan children today eat imported processed foods in bulk. Like many Samoans, the doctor’s opinion is that a return to ancestral foods will mitigate dietary diseases in the region. However, is the answer that simple? Is removing imported foods from Samoan society and culture feasible?

Considering that imported processed foods have been an integral part of Samoan food culture for over a century, and that gifting and eating in bulk is intertwined with Samoan cultural norms, it becomes much harder to grapple with the possibility of ridding Samoan culture of imported foods. In fact, many Samoans dedicated to making these changes are adopting and adapting non-Samoan means of improving public health. For example, Zumba classes and CrossFit groups have become increasingly popular ways to stay active, and fruits and leafy green vegetables are being pushed by government and grassroots campaigns to try to convince Samoans to eat more healthfully. In this sense, the notion of returning to Sāmoa’s food past is complicated by the fact that innovative, contemporary public health practices are simultaneously promoted as the answer to the problems of Sāmoa’s food present. On the other hand, some farmers are attempting to grow a kind of slow food movement in Sāmoa, predicated on revitalizing ancestral agricultural practices and diets. This suggests that perhaps looking to the past can provide a path to a healthy and sustainable food future. On the other other hand, what does a “back to the future” approach mean for Samoans who feel that eating imported foods is the mark of a thriving people? And who are activists—especially outsider activists—to tell Samoans that they cannot eat the same foods that have given so much meaning to cultural exchanges for so long?

This short text does not propose clear answers to the complicated questions it poses. Perhaps, however, readers will now be interested to further engage with food studies in Sāmoa, and Oceania more broadly, to address things like food adoption and adaptation, the relationship between food and health, the entanglement of food and colonialism, and the complications of eradicating imported foods from Indigenous Oceanian societies and cultures. The assignments following this chapter provide an opportunity to begin that engagement, and welcome all readers to begin discussing these serious issues with one another.

Discussion Questions

- Given what you learned in this chapter about Samoan food culture, what is the role of food in the cultures with which you are familiar? In what ways is Samoan food culture distinct from and/or similar to these food cultures?

- What are some of the ways that dietary disease can be linked to food culture? How can food culture help prevent dietary disease?

- What is the link between colonialism and dietary disease?

- In its concluding section, this chapter asks if the answer to Sāmoa’s (and Oceania’s) dietary disease crisis is taking a “back to the future” approach? What might be learned from looking at diets from the past? What might be learned from contemporary public health practices?

Exercises

Exploring Food in Print

While it is not always possible to travel to Oceanic islands to speak directly with people to learn about the past and present of their food culture, much can be learned from materials housed in archives. Go to the National University of Australia’s TROVE digital archives and browse through issues of The Pacific Islands Monthly. While it is important to remember that this magazine was written for a Euro-American audience, it contains advertisements and stories about food across Oceania. Click on the “Browse this collection” button, and then click on any of the thumbnails that appear, while also scrolling or using the drop-down menu to see more recent issues. Once you select an issue, use the search tool to look for things like “food,” “beef,” “taro,” “beer,” “cookies,” “diabetes,” or any other food-related search term you can think of.

Write a description of what you found in the issue you selected, considering the following questions:

- What did you learn about food and food culture in Oceania?

- In the descriptions or stories about food that you read, what words or phrases stuck out for you?

- What did the images tell you about food culture in the region?

- How might the magazine’s audience be affected by the choice of food stories and/or advertisements in the issue?

Exploring Food in Song

Listen to the popular Samoan song “Oka oka laʻu hani,” and read the lyrics below as you listen. What kinds of foods does the song tell about, and how does the song use food symbolism? What might this tell you about changes in Samoan food culture that took place during the 20th century? (The song was written in the 1930s, and this version, performed by the Five Stars, is from the 1980s.)

|

Oka Oka la’u Hani o La’u hani faasilisili ou te faatusaina i se apa helapi po’o se pisupo sili po’o se masikeke mai Fiti po’o sina sapasui o ni tamato ma ni pi Afai lava ua tonu ua tonu lou finagalo ta faaipoipo avane i le malo e leaga o le taʻatua e tele ai o le tiapolo pe fai sau pepe o le pepe o le pō Tia, tia tofa o le a ta teteʻa e leai o se mamao alaga i gauta avanoa sau taimi telefoni ane se itula pe fai sau leta avane i se motokā |

Oh oh my honey My dearest honey Who I compare to a can of Hellaby’s [corned beef], Or the very best corned beef, Or some cookies/biscuits from Fiji, Or the very best Chop Suey, With the tomatoes and peas If it’s agreeable for you With the will of your heart We’ll get married In accordance with the law For it’s wrong to just play around There is a devil [That is an act of the devil] And if you have a baby It will be a baby of the night [a demon] Dear, dear, goodbye We are parting ways But the distance isn’t too great Shout inland When you have the time Telephone me at some hour Or write a letter And send it to me by motorcar |

Exploring Food in Film

Watch the documentary “Samoa Diabetes Epidemic: Part 4” from Attitude, and write a one- to two-page summary that reflects your understanding of Sāmoa’s contemporary health crisis. Drawing on what you learned in this chapter and in the film, offer your thoughts on potential solutions to this dietary “tsunami in the Pacific.”

Additional Resources

Teaching Oceania, a resource compiled by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa’s Center for Pacific Islands Studies (CPIS)

Laudan, R. 2013. “Modern Cuisines: The Globalization of Middling Cuisines, 1920–2000,” in Laudan, Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sharma, J. 2012. “Food and Empire,” in Jeffrey Pilcher, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Food History. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

On “Gastrocolonialism,” see: Craig Santos Perez, “Facing Hawaiʻi’s Future – Book Review,” Kenyon Review (July 2013).

- Note that in this text, the word "Samoan" is written without a macron over the a (ā). This follows Samoan linguist expertise, which notes that "Samoan" is not a Samoan word, but an English word, and English does not standardly use macrons. The Samoan word would either be "Gagana Sāmoa," or "Sāmoa," meaning "Samoan language" or "of Samoa," respectively. ↵