1.3: Technical Sketching

- Page ID

- 5184

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\(\newcommand{\longvect}{\overrightarrow}\)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Many times out in the field you are working on sketches drawn on anything from napkins, cardboard, wood scrapes or any flat surface. Don’t get me wrong, you will work projects with professionally produced drawings but sometimes you have to work with what you have.

Being able to make technical sketches doesn’t mean you need to be an artist; and sketching isn’t difficult if you follow a few simple rules. You may be a little slow at first, but with some practice you will be able to turn out reasonably good sketches without too much effort.

You are not going to be judged as a professional draftsperson or architect but you need to be able to describe, with lines what you are needing built, repaired or modified. This take practice and is a very important skill to develop.

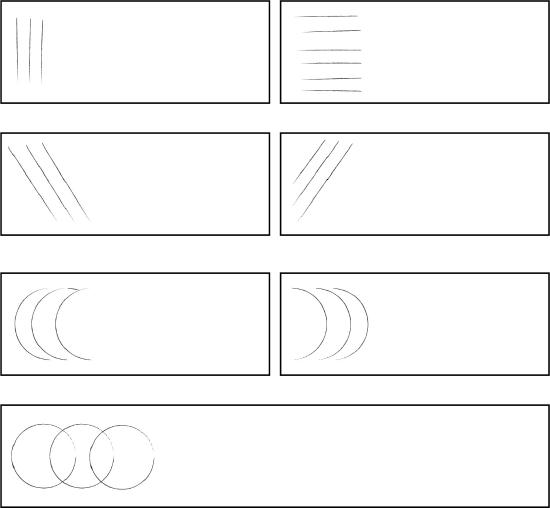

Sketching Techniques

All you need to start is a pencil and some paper. A soft pencil works best for most people, so try a #2 or an F. Keep the pencil sharp, but not too sharp: hold it with a grip firm enough for control, but not so tight that your arm isn’t relaxed. Don’t draw heavily at first. That way it is easier to erase without smudging. Darken the sketch when it begins to shape up the way you want it.

It’s generally best to begin sketching with plain paper, although some people like to use grid paper. On the job, you may find yourself sketching on the back of a work order or piece of packing crate. In any case, it’s learning to sketch quickly and effectively that’s important.

Here are some limbering up exercises wot get you started. To keep your pencil sharper longer, and for more even lines widths, try turning your pencil slowly while completing the lines in the exercises below.

Next, try sketching the objects on this page. Make your sketches as much like the examples as possible. Remember; sketching means freehand drawing. No Straightedges, compass, coins, etc!

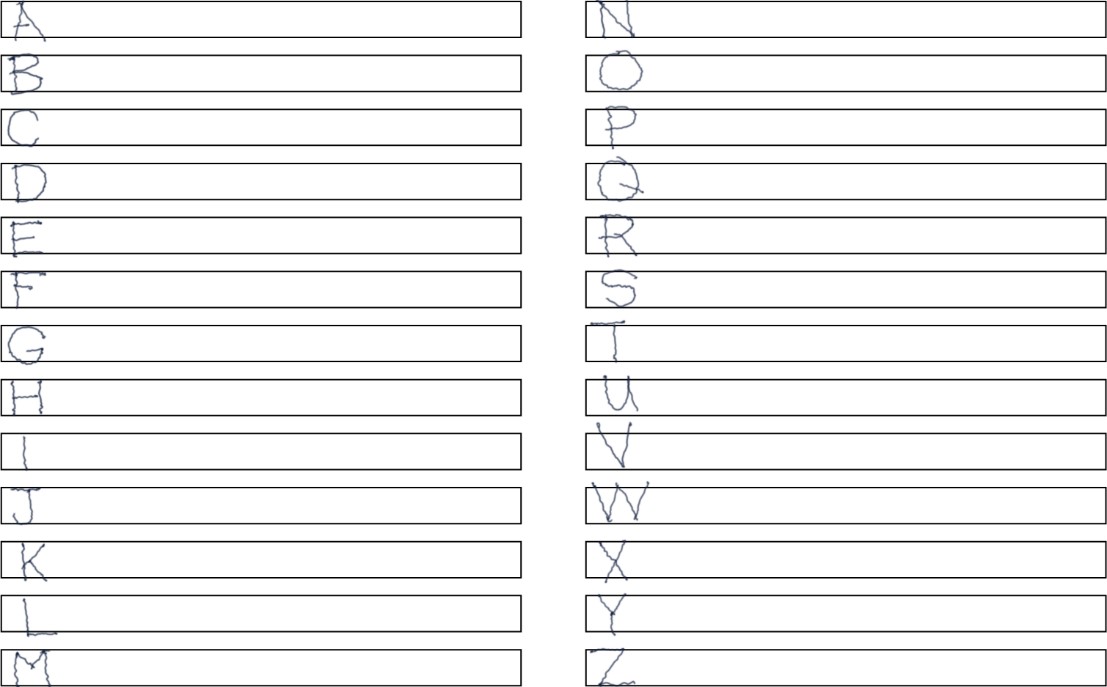

Lettering

Now that you are warmed up, we will take the straight and curved lines from the sketching exercise and use them to form letters. The entire alphabet can be formed from the straight and curved lines you have practiced.

Look at the lettering below. If your printing is similar, and is easily readable, you can skip this exercise and go on to oblique sketching. If not, do some practicing. Some of the work ahead (and tests) require good lettering.

Remember, the most important requirement of good lettering is legibility. There is no use making a drawing if the person looking at drawing cannot read your writing.

Oblique Sketching

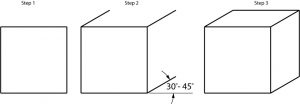

Oblique sketches are a type of pictorial having one plane parallel to the drawing surface, and the visible side sketched at an angle. Usually, that angle works best at 30◦ to 45◦, or somewhat in between. Beginners often have trouble keeping the 30◦ or 45◦ lines as the same angle. If that happens, your sketch will look distorted.

Here’s how to sketch an oblique cube in three steps:

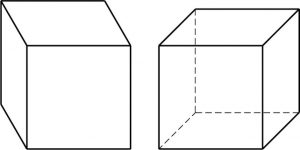

Possibly you might want to show the left side of the cube, or perhaps draw the hidden lines, as at the right;

In the spaces below, sketch oblique cubes as indicated.

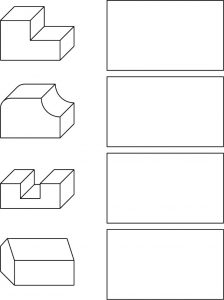

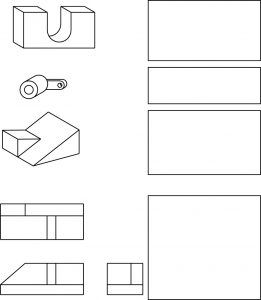

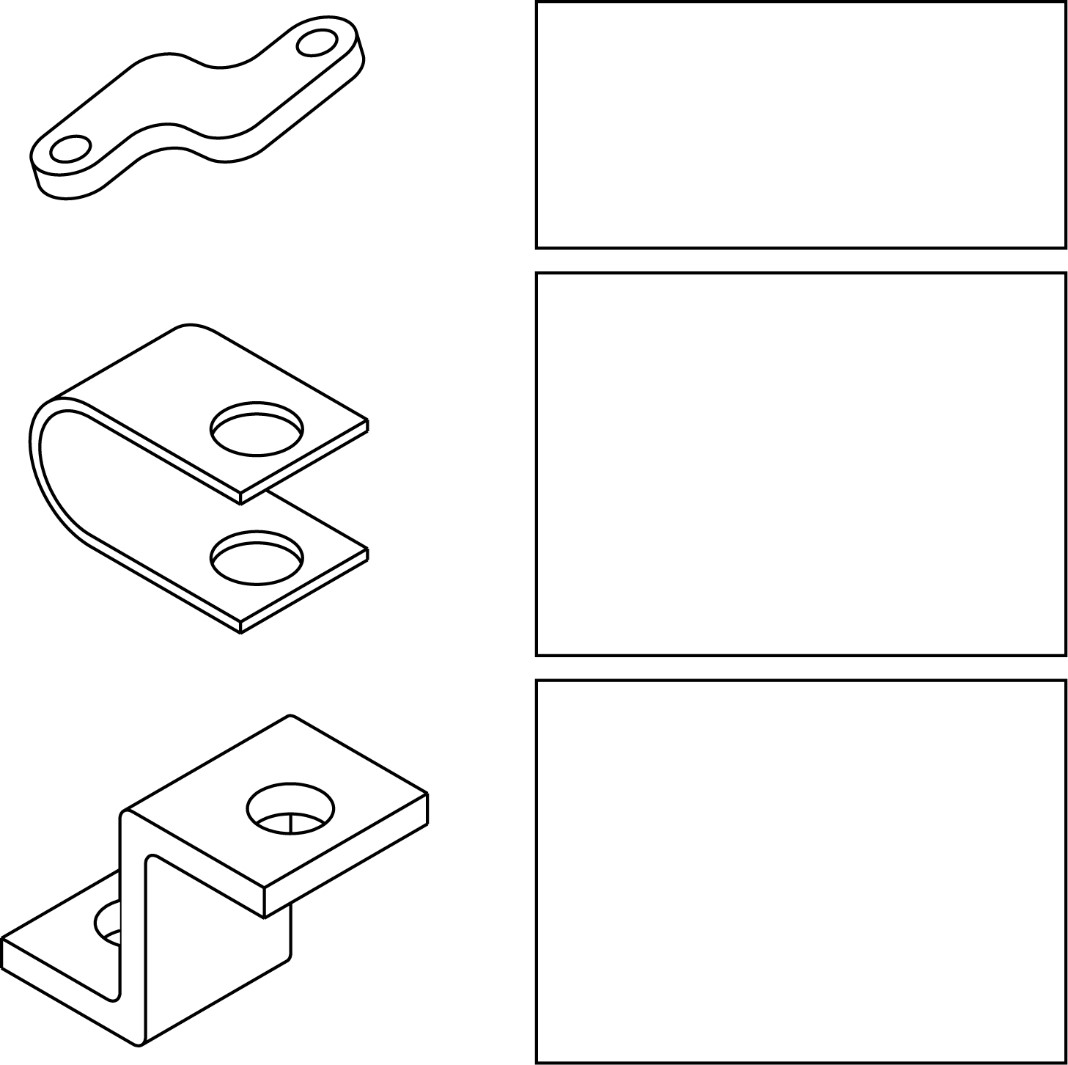

Sketch these objects in oblique, as shown:

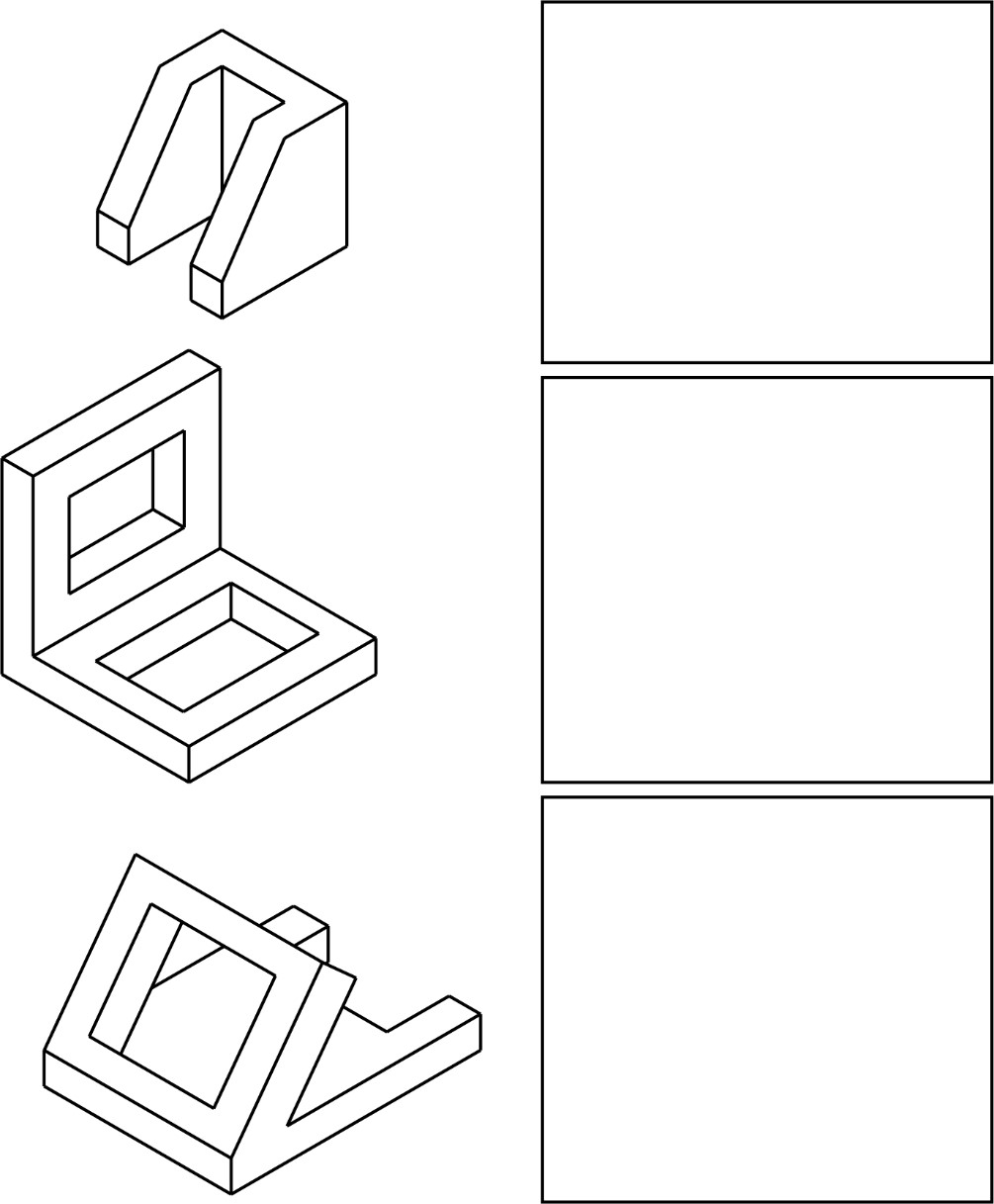

In this more difficult exercise, you are to make oblique sketches of the objects shown. The third problem is drawn in isometric. You are to sketch it in oblique. Convert problem four from orthographic to an oblique sketch.

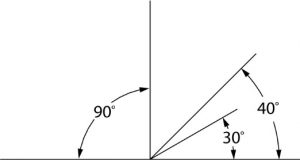

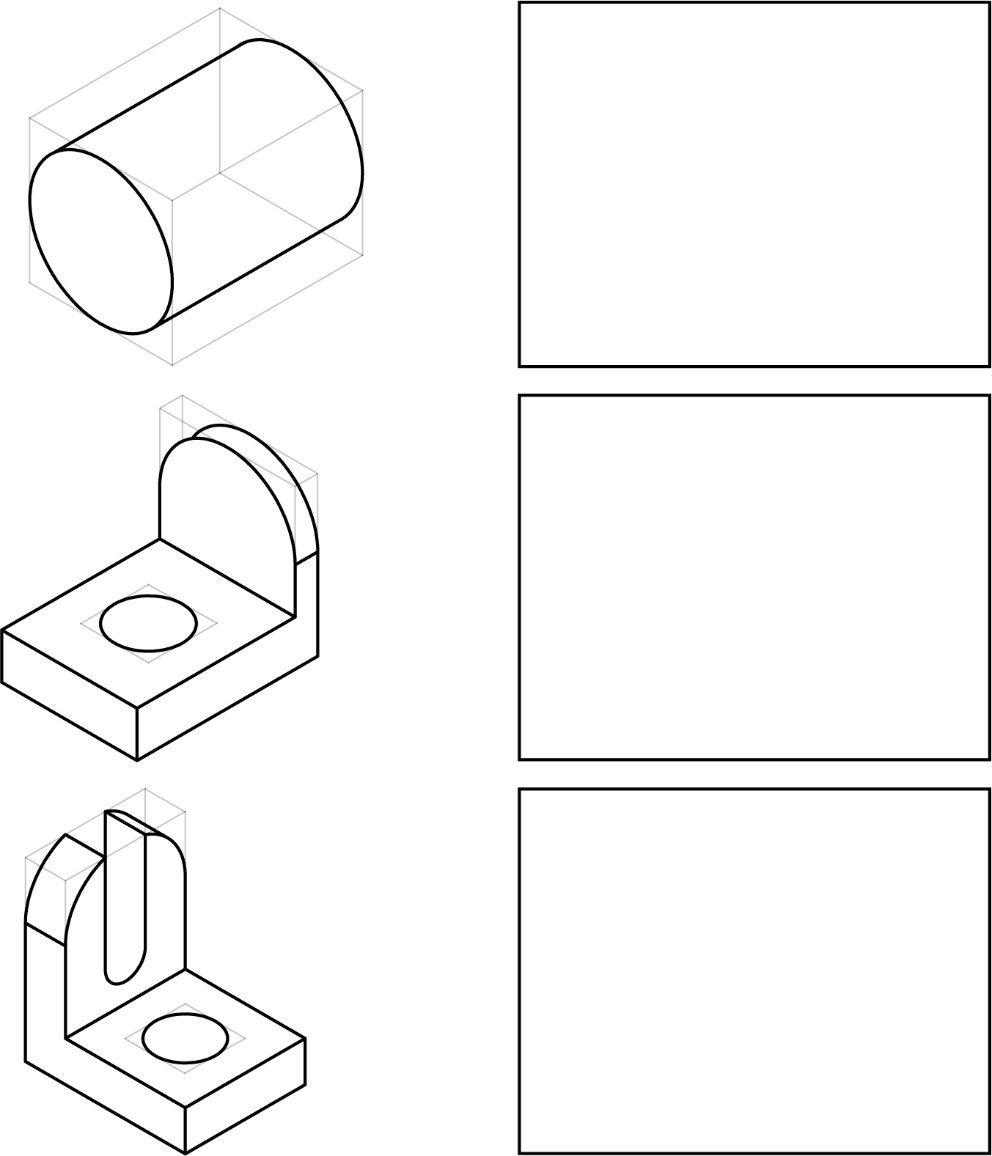

Isometric Sketching

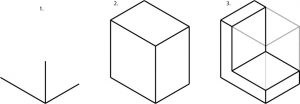

Isometric sketches, unlike oblique, must maintain an angle very close to 30°.

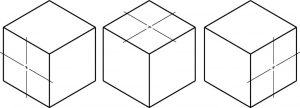

Therefore, to get the “feel” of an isometric, try sketching 30° angles in this exercise:

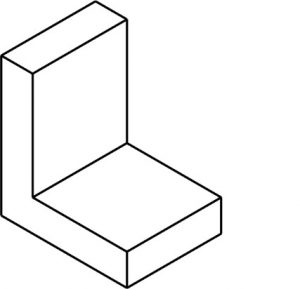

Sketching in isometric can be done in different ways. Generally, it’s recommended that you start and the bottom of the object and “box it in”, thereby enclosing it within a rectangular framework. For example, if we were to take a simple object like this,

The steps needed to sketch it in isometric would be;

The unnecessary lines are then removed, leaving the object. Once you gain some practice at this, it will be possible for you to make an ISO drawing without the “guide” lines. It is important to use them early on the help train your brain.

To the beginner, building a “frame” before sketching the object often seems unnecessary. That may be true with simple objects. However, when things become more complex, a frame gives you a means of developing the various parts in an organized way. Without such guidelines you can easily “lose” your sketch.

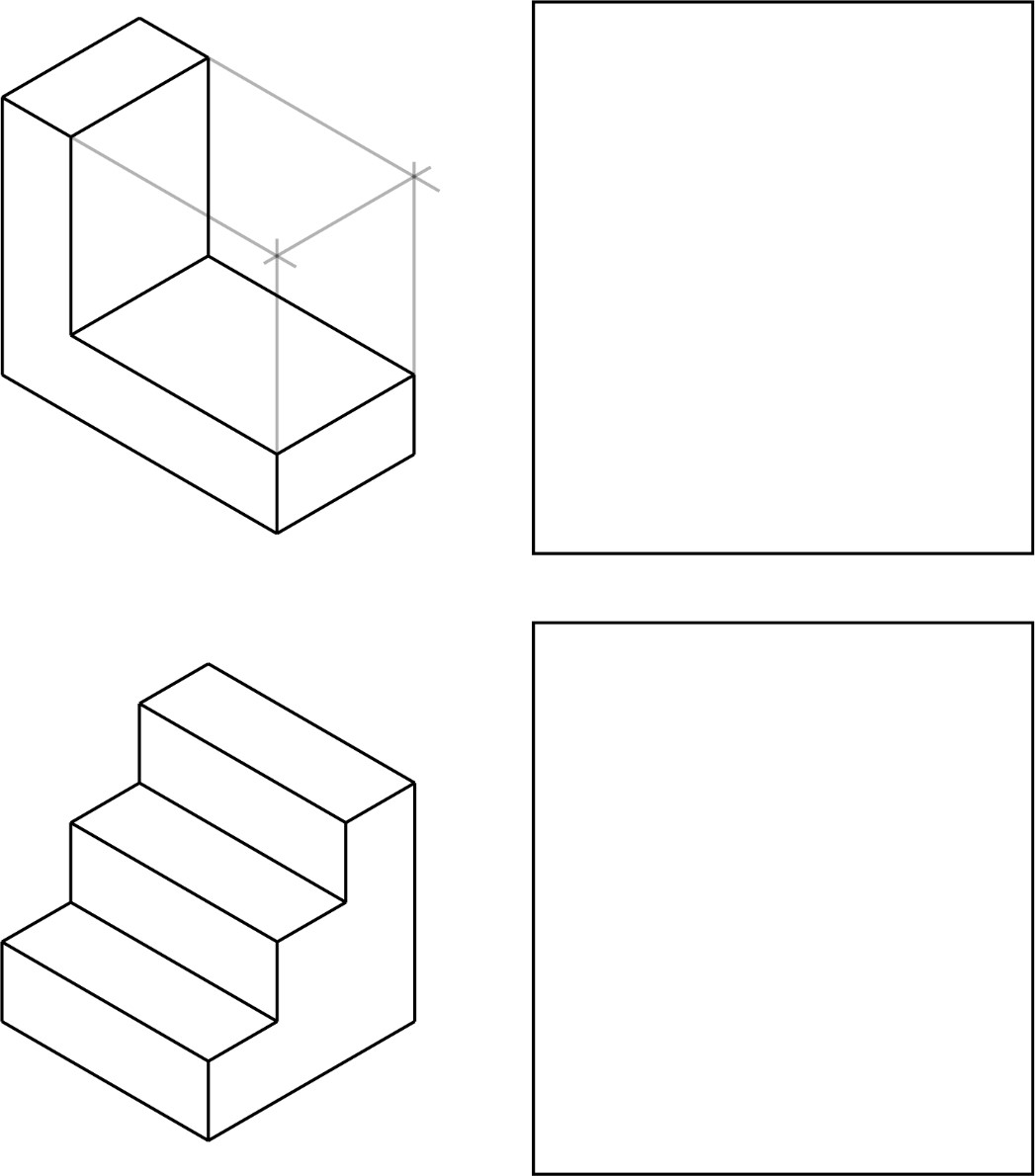

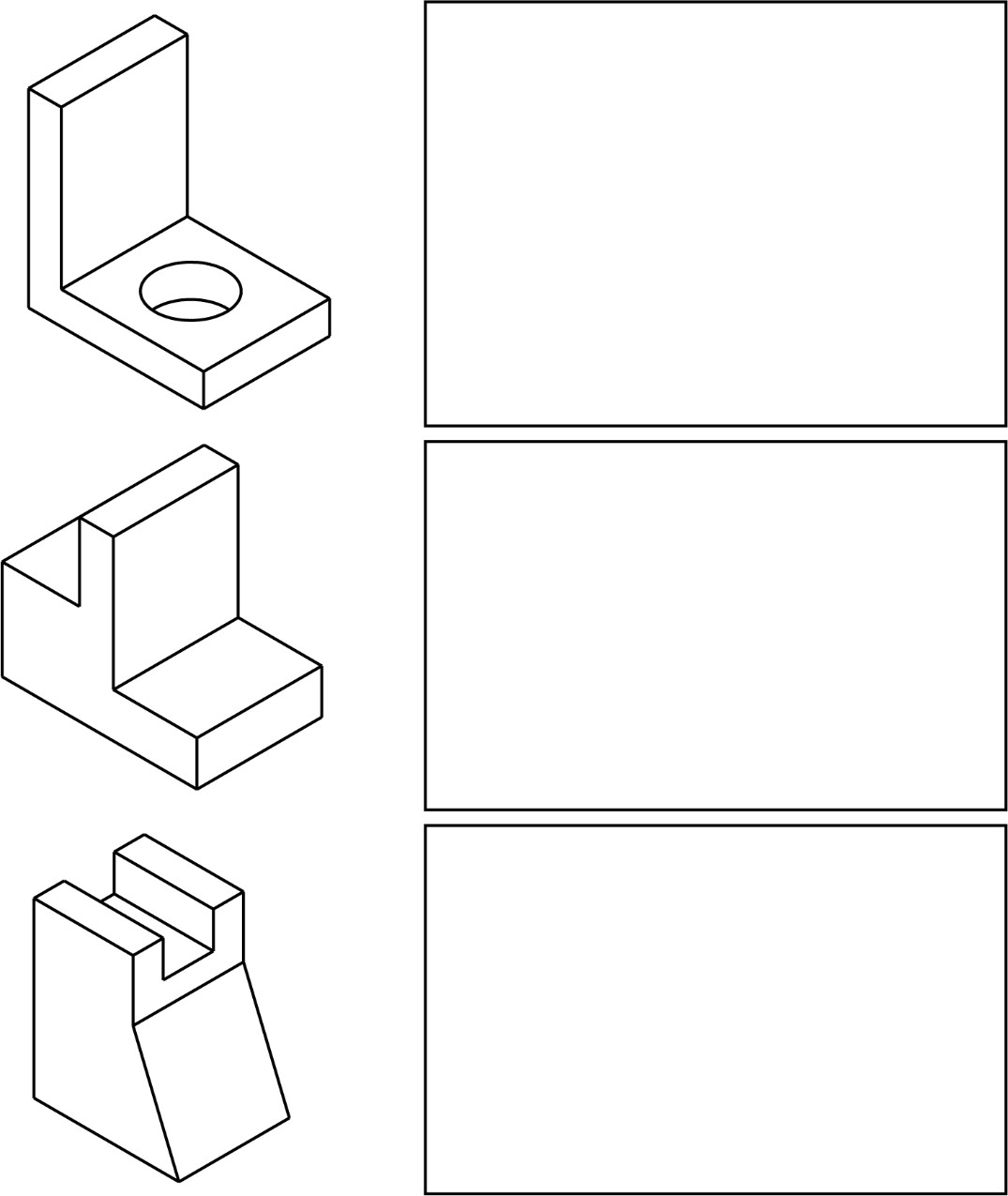

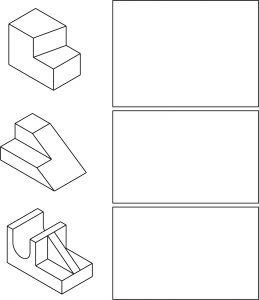

Sketch the examples given, using guidelines as shown in the first exercise. Draw the guidelines lightly. Notice that 3 and 5 require the use of non-isometric lines. Since those lines are not at 30◦, it is best to connect the end points of those lines after the sketch nears completion.

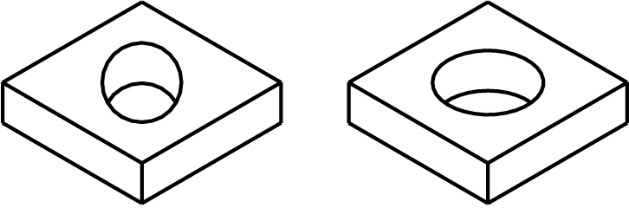

Circles and arcs, when sketched in isometric, become elliptical in shape. If a circle is used, it will appear distorted, as in this example:

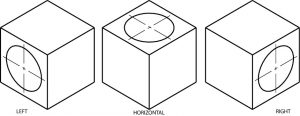

In sketching isometric circles and arcs, there are three positions in which they are normally sketched, depending upon the surface where the circular feature is located. Those surfaces, or picture planes are:

On the cube shapes below sketch ellipses as on the examples above.

You may also want to practice sketching ellipses on the other surfaces of the cubes.

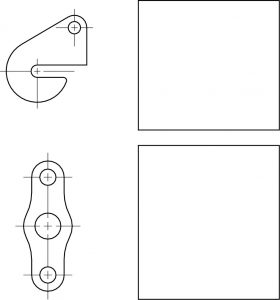

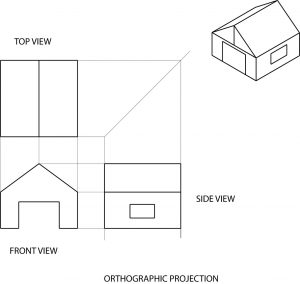

Orthographic Sketching

Of all the methods of making drawings, orthographic projection is the most commonly used by draftsperson. Although the other methods serve their purposes, they cannot always show the parts of an object as well as orthographic representation.

Orthographic projection is a system of projecting from view to view to graphically describe the object. As a way of reviewing, study the views of the small garage in this drawing. Notice the location and relationship of each view to the other views.

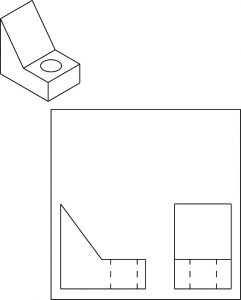

The important thing to remember in orthographic sketching is the alignment of views. The top view is projected directly above the front view. The front and side view also line up with each other. The height, width, and length of the object must remain the same from view to view. There should be enough distance between the views to prevent crowding; and to leave room for dimensions.

Produce a top view in the drawing below.

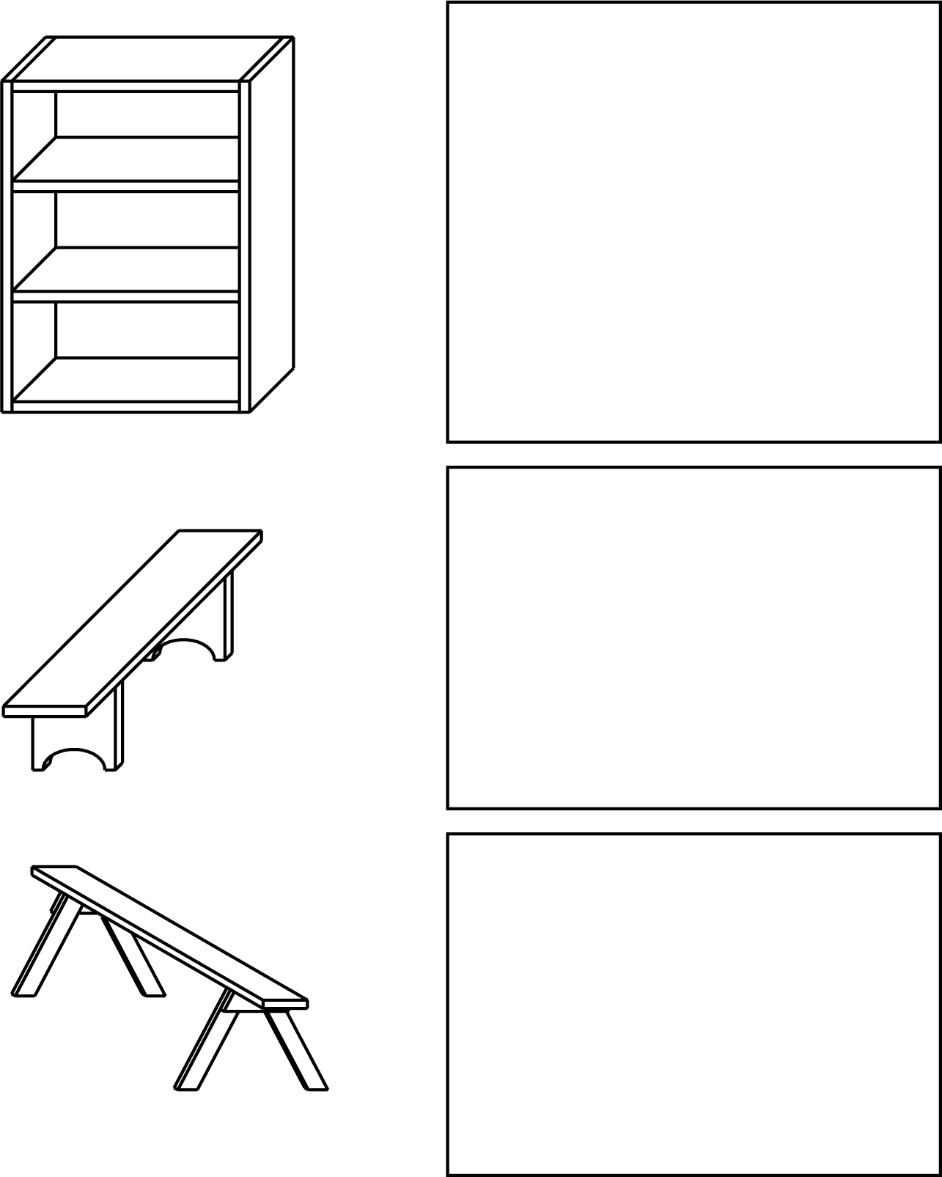

Sketch each object in orthographic in the spaces on the right. Remember, the idea is to project! Front, top and right side view.

“On-THE-SPOT” Sketching

Now that you have learned the three different methods of sketching, it is time to make sketches you can place in front of you and touch, rather that sketching from drawings on paper.

Sketching “ON-THE-SPOT” is a standard industry practice. A piece of machinery needs to be changed, a support needs to be added, or pictorial information in some way requires a sketch.

Instructor will give you an object to sketch…

You will need to produce an isometric of the object and also an orthographic drawing with as many views as required to show details of object to be built.