5.3: Shelf Life and Abuse Testing

- Page ID

- 17831

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)How long will your product last?

In this chapter, you will learn how to test your product to determine the shelf life and/or how much abuse your product can take.

- It is important to know how long your product will stay at the quality the consumer expects.

- Typically, at least to a certain extent, we want the product to have as long of shelf life as possible. This gives time to make the product, ship the product to a distributor, then ship the product to the grocery store, have a consumer buy the product, take it home (possibly store it), and then consume.

- Your team will need to determine the mode of failure – what will go wrong with your product first – spoilage microorganism growth, moisture migration, color loss, flavor change, etc.

Shelf Life Definition

Shelf life is the period of time under defined conditions of storage, after manufacture or packing, for which a food product will remain safe and be fit for use. During this period of shelf life, the product should:

- Retain its desired sensory, chemical, physical, functional, or microbiological characteristics

- Comply with any label declaration of nutrition information when stored according to the recommended conditions (Man, 2015) [1]

Shelf Life Types

All foods deteriorate, often in different ways and at different rates. Types of shelf life are shown below.

- Microbiological Shelf Life – example: mold spoilage growth

- Chemical Shelf Life – example: lipid oxidation

- Sensory Shelf Life – color, flavor, or texture change

- The shelf life of a food product is intended to reflect the overall effect of these different aspects, ideally under a set of specified storage conditions.

Food Safety and Shelf Life Considerations

- The food has to be safe to consume first and foremost.

- Unless selling a raw product, ensuring your product is safe to consume is typically done during processing and packaging (heat steps, metal detectors, etc. – think CCPs or Preventative Controls).

- Microbial shelf-life concerns are typically from spoilage microorganisms, especially yeasts & molds.

Intrinsic & Extrinsic Factors to Consider

For some products, it is fairly straightforward to determine the mode of failure. For other, especially new products, it may be less clear. Performing accelerated and real-time shelf life testing will be needed to confirm the mode or modes of failure, but it can be helpful to think through the intrinsic and extrinsic factors of your product to start with an educated guess.

Intrinsic Factors

- Raw materials

- Product composition and formulation

- Product structure

- Product make‐up

- Water activity value (Aw)

- pH value and acidity (total acidity and the type of acid)

- Availability of oxygen and redox potential (Eh)

Extrinsic Factors

- Processing and preservation

- Hygiene

- Packaging materials and system

- Storage, distribution, and retail display (in particular with respect to exposure to light, fluctuating temperature, and humidity, and elevated or depressed temperature and humidity)

- Other factors – consumer handling and use (Man, 2015) [2]

Accelerated Shelf Life Testing

- Accelerated shelf-life testing (ASLT) is used to shorten the time required to estimate a shelf life which otherwise can take an unrealistically long time to determine (at least in terms of new product development and wanting to launch a product as soon as possible).

- Real-time shelf life testing also is needed but can be done/finished after the new product is already launched. The shelf life is then updated as applicable.

- The most common form of ASLT is storing food at an elevated temperature.

- The assumption is that by storing food (or drink) at a higher temperature, any adverse effect on its storage behavior and hence shelf life may become apparent sooner.

- The shelf life under normal storage conditions can then be estimated by extrapolation using the data obtained from the accelerated testing.

Accelerated Shelf Life Testing Benefits and Drawbacks

This is not a perfect system and works better for some products than others.

Benefits

- Accelerated tests are particularly useful when the patterns of changes are practically identical under both normal and accelerated storage.

- This allows the shelf life under normal storage to be predicted with a high degree of certainty from the accelerated shelf life results.

- Accelerated shelf-life testing works well for oil rancidity predictions, especially in products such as chips and nuts.

Drawbacks

- Tends to be product-specific; results have to be interpreted carefully based on detailed knowledge

- Frozen product accelerated testing can be difficult because thawing significantly changes product characteristics.

- If spoilage is the main concern, increasing the hold temperature may cause other classes of microbes to grow.

Steps to Determine Accelerated Shelf-Life

- Define product (and packaging) to be put into conditions with a set timeframe

- Identify the conditions and type(s) of test needed

- Define mode of failure

- Implement set-up and testing

- Analyze results

- Predict real-time shelf life

Abuse Testing

Abuse testing is done to simulate the conditions food products will go through between production and consumption. In some instances, especially for this course, abuse testing is used instead of accelerated shelf-life testing.

Physical Abuse – for fragile products

- Simulates the shaking or movement of a product riding on a truck and abuse from dropping the product.

- Drop tests are easy to perform and then evaluate product change.

- This testing indicates how durable the product and corresponding packaging is through distribution and movement from the grocery store to the consumer.

Temperature Abuse – for refrigerated and especially frozen products

- Simulates freeze-thaw cycles in the grocery store, consumers buying and taking the product home, and inefficient storage at home

- Abuse testing indicates how much temperature abuse the product can take before its quality is no longer acceptable.

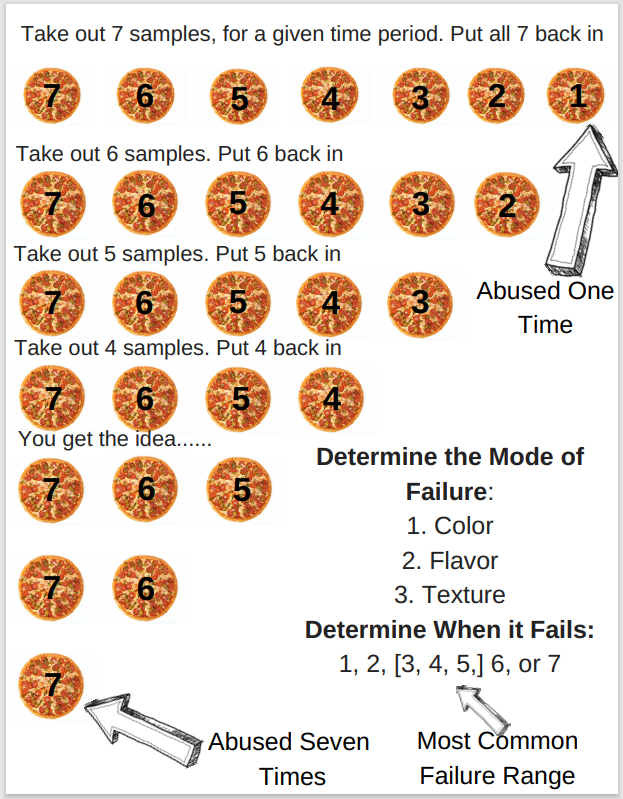

Seven-Cycle Abuse Testing – an industry test method to determine how much abuse a product can withstand before the product quality is unacceptable.

The type and duration of abuse are dependent on the product characteristics and size. For frozen products, the idea is for the product to be temperature abused with some surface melting, but not completely melt or come to room temperature during the abuse. Refrigerated products can sit out at room temperature for abuse, but the lengths of time may be longer than the frozen products. Below is an example of the 7 cycles of abuse. All 7 samples are abused, then all samples are evaluated together to determine the mode of failure and the cycle that the product was no longer acceptable.

Determining an Accelerated Shelf Life Test or Abuse Test for Your Product

- Think about your product characteristics.

- Which characteristics are the most important?

- Which characteristics are the most likely to deteriorate first?

From your answers above:

- Does abuse testing or accelerated shelf-life make more sense?

- Look at the 7-cycle example to set up your abuse testing –OR-

- Research accelerated shelf-life studies of similar products to determine your parameters (typically time and temperature, sometimes relative humidity).

State how you chose your testing, what the predicted mode of failure is, and if the product fails after only one or two abuse cycles, what steps you would take to improve the resiliency/shelf life of the product. If abuse testing is used, it will be helpful to look up the shelf life of other similar products to set the shelf life specification.

Shelf Life References with Examples

Cereal Foods World – Not Your Mentor’s Shelf Life Methods (pdf)

Italian Journal of Food Safety – Experimental Accelerated Shelf Life Determination of Ready-To-Eat Processed Foods (pdf)

- Introduction to shelf life of foods – frequently asked questions. (2015). In Shelf Life (pp. 1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1...1118346235.ch1 ↵

- Introduction to shelf life of foods – frequently asked questions. (2015). In Shelf Life (pp. 11-12). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1...1118346235.ch1 ↵