8.2: Educational Design Research as a Source of Data

- Page ID

- 5673

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Scholars and practitioners in many fields have developed use-inspired research methods specific to the problems they solve and the interventions they design. Educational design research (McKenny & Reeves, 2012). McKenny & Reeves (2014) captured the dual nature of educational design as a method for designing interventions and a method for generating theory, as they noted it is motivated by “the quest for ‘what works’ such that it is underpinned by a concern for how, when, and why is evident….” (p. 23). They further describe educational design research as a process that is:

- Theoretically oriented as it is both grounded in current and accepted knowledge and it seeks to contribute new knowledge;

- Interventionist as it is undertaken to improve products and processes for teaching and learning in classrooms;

- Collaborative as the process incorporates expert input from stakeholders who approach the problem from multiple perspectives;

- Naturalistic as it both recognizes and explores the complexity of educational processes and it is conducted within the setting where it is practiced (this is opposed to the pure researcher’s attempt to isolate and control factors, thus simplifying the setting);

- Iterative as each phase is complete only after several cycles of inquiry and discourse.

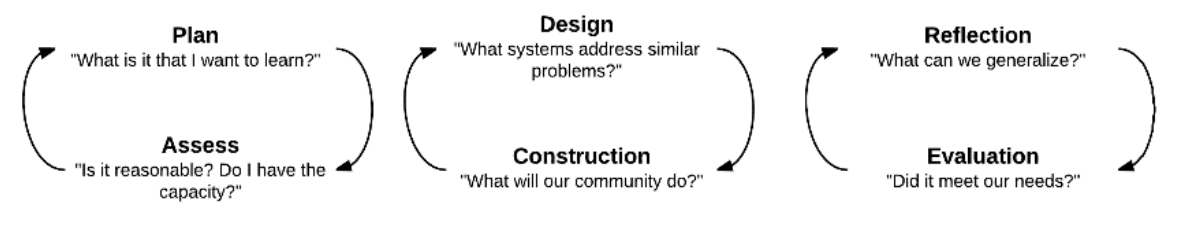

Projects in educational design research typically comprise three phases (see Figure 7.3.1), and each phase addresses the problem as it is instantiated in the local school and it is either grounded in or contributes to the research or professional literature. For school IT managers, the analysis/ exploration phase of educational design research is focused on understanding the existing problem, how it can be improved, and what will be observed when it is improved. These discussions typically engage the members of the technology planning committee who are the leaders among the IT managers. Design/ construction finds school IT managers designing and redesigning interventions; this phase is most effective when it is grounded in the planning cycle described in Chapter 6. Reflection/ evaluation finds them determining if the solution was successful and also articulating generalizations that can inform the participants’ further work and that can be shared with the greater community of school IT managers.

Figure \(\PageIndex{1}\): Phases of educational design research (adapted from Ackerman, in press)

Defining Improvement

Efficacious IT management depends on all participants maintaining a shared understanding of the problem and the intended improvements; it also depends on discourse so that the participants communicate their perspectives so the systems are properly configured, appropriate for students and teachers, and reasonable given the norms and limits of the school. This can only be accomplished through effective communication, which is threatened by the differences that mark the groups.

Carl Bereiter (2002), an educational psychologist, described discourse as a form of professional conversation through which psychologists can “converse, criticize one another’s ideas, suggest questions for further research, and—not least—argue constructively about their differences” (p. 86). This description appears to present discourse as a type of interaction similar to the discussion and debate that characterizes political dialogue and decision making. Bereiter specifies, however, discourse is grounded in data and evidence, so it is a tool for scientific inquiry rather than for political discussions. Bereiter extends the application of discourse to planning for education, and specifically he suggests progressive discourse as a method whereby planners can define continuous improvement, implement interventions, and assess the effectiveness of those interventions. In general, progressive discourse is the work of expanding fact to improve conceptual artifacts; this work necessitates a nonsectarian approach to data and decisions.

Planning is the process by which spoken ideas and written language is converted in to actions. Conceptual artifacts are those actions that can be observed in social systems and that are described in the language used to express plans. Progressive discourse depends on planners sharing an understanding of both the language used to capture plans and the actions that will be observed when those plans are realized. Scardamelia and Bereiter (2006) observed progressive discourse depends on participants’ “commitment to seek common understanding rather than merely agreement” (p. 102). If IT managers agree on the language they use to define strategic and logistic goals, but not on what they will observe when the logistic goal is achieved, then they do not share a conceptual artifact. Their plans and interventions are likely to be inefficient and ineffective.

In education, we can observe many situations in which different conceptual artifacts are instantiated. There is, for example, a growing interest in using games as a method of motivating students and giving context for deeper understanding. Ke (2016) observed, “A learning game is supposed to provide structured and immersive problem-solving experiences that enable development of both knowledge and a ‘way of knowing’ to be transferred to situation outside of the original context of gaming or learning” (p. 221). Contained within that conceptual artifact of “learning games” is cognitive activity that causes learners to interact with information and that leads to understanding sufficiently sophisticated that it can be used flexibly. Such games have been found to contribute to effective and motivating learning environments (Wouters & van Oostendorp, 2017).

Ke’s conceptual artifact of learning games contrasted with the observation I made while visiting a school and watching students who were completing a computerized test preparation program. After students had correctly answered a certain number of questions, the program launched an arcade-style game that had no connection to the content. It appeared the games were intended to motivate the students and provide a reward for giving correct answers. The principal identified this practice as an example of how his teachers were “integrating educational games into their lessons.” The students had discovered the arcade games appeared after a certain number of correct answers and they were “gaming” the system by randomly answering questions by randomly submitting answers in a strategy that led to the games appearing more quickly than if they tried to answer the questions. While the value of determining how to get to the games without answering the questions can be debated, it did not require students to engage with the content. We can reasonably conclude the principal and Ke did not share a conceptual artifact regarding games.

If the principal and Ke were on a technology planning committee together, then we can assume they might both agree that “learning games can be valuable,” but their understandings of the experiences that represent learning games would be different. They would agree on language, but not actions, so they would not share a conceptual artifact. The planning committee with Ke and the principal would find it necessary to continue to discuss learning games and resolve their differences so that decisions about what comprise “learning games” were common to the pair.

As progressive discourse proceeds, the participants build greater knowledge from outside sources (new research and new discoveries) and from inside sources (experiences with their own system and community). This knowledge can cause managers to reconsider the definition and realization of a conceptual artifact. When redefining conceptual artifacts, IT managers may be tempted to accept a broader definition, but new and more nuanced conceptual artifacts are generally improvements over the current ones. In this case, the committee may choose to improve the conceptual artifact by differentiating “learning games” from “games for reward” and proceeding with two conceptual artifacts rather than using one definition that is too broadly applied. Improvement of conceptual artifacts occurs when:

- Planners develop a more sophisticated understanding of what they intend in the conceptual artifacts;

- Conceptual artifacts are replaced with more precise ones;

- Managers communicate the conceptual artifacts so more individuals representing more stakeholders share the conceptual artifact;

- IT managers take steps so the conceptual artifacts are implemented with increased efficiency;

- Conceptual artifacts are implemented with greater effectiveness by increasing alignment between conceptual artifact and practice, removing those practices that are the least aligned, or using conceptual artifacts to frame activity in situations where they are not currently used.

Progressive discourse is especially useful during the analysis/ exploration of a problem. It is during this phase of educational design research (McKenny & Reeves, 2012) that IT managers improve their understanding of the problem and the conceptual artifacts that represent solutions. This is a research activity, thus it cannot be undertaken to support a political conclusion, to accommodate economic circumstances, or to confirm a decision been made prior to beginning. Ignoring facts because they appear to violate one’s political, religious, economic, or pedagogical sensibilities or because they are contrary to those espoused by another who is more powerful is also inconsistent with the process. Equally inconsistent is selecting evidence so it conforms to preferred conclusions; educational design research and progressive discourse builds knowledge upon incomplete, but improving, evidence that is reasonably and logically analyzed in a manner that researchers approach evidence rather than through political preferences. These may be reasons to accept decisions, but decision-makers have a responsibility to be transparent and to identify the actual reason for making the decision.

Schools, of course, are political organizations and different stakeholders will perceive the value of conceptual artifacts their improvements differently. First, individuals’ understanding of the artifacts and acceptance of the values embodied in the conceptual artifacts varies. Because of this, one individual (or groups of individuals) may perceive a change to be an improvement while others perceive the same change to be a degradation; this is unavoidable as it arises from the wicked (Rittel & Weber, 1973) nature of school planning. Second, some participants in the progressive discourse are likely to have a more sophisticated understanding of the conceptual artifacts than others, so they may find it necessary to explain their understanding and build others’ understanding of the conceptual artifacts. Further, those with less sophisticated understanding may find their ideas challenged by unfamiliar conceptual artifacts. Third, understanding of and value placed on the conceptual artifacts becomes more precarious when including stakeholders who are most removed from the operation of the organization.

Consider again the example of learning games; it illustrates the implications for various stakeholders when a conceptual artifact improves. If the planning committee decided the arcade-style games in the test preparation violate the accepted conceptual artifact of learning games, the committee may recommend banning arcadestyle games in the school. A teacher who uses such games to improve students’ speed at recalling math facts may find this “improvement” weakens her instruction. That math teacher may argue for a more precise understanding of arcade-style games, so those she uses are recognized as different from those in the testpreparation program.

If discussions about the role of games in the classroom spilled into the public (which they often do in today’s social mediarich landscape), then the continued use of learning games, regardless of their instructional value, might be challenged by those whose oppose game playing in any form by students, especially those stakeholders who do not see students engaged with games in classrooms. This could change political pressures making progressive discourse more difficult.

Designing Interventions

IT managers seek to improve conceptual artifacts through designing interventions. Decisions about which conceptual artifacts to improve and how to improve them are made as IT managers explore/ analyze the local situation. Interventions are designed through iterative processes informed by the technology planning cycle shown in Figure 6.2.1.

There are deep connections and similarities between design and research. Both activities progress through problem setting (understanding the context and nature of the problem), problem framing (to understand possible solutions) and problem solving (taking actions to reach logistic goals). Both design and research find participants understanding phenomena, which affects decisions and actions that are evaluated for improvement of idea or interventions. “Design itself is a process of trying and evaluating multiple ideas. It may build from ideas, or develop concepts and philosophies along the way. In addition, designers, throughout the course of their work, revisit their values and design decisions” (Hokenson, 2012, p. 72). This view of design supports the iterative nature of design/ construction of educational design research. Initial designs are planned and constructed in response to new discoveries made by IT managers; these discoveries can come from the literature or from deeper understanding of the local instances. In terms of progressive discourse, redesign/ reconstruction decisions are made as conceptual artifacts are improved.

One of the challenges that has been recognized in school IT planning is the fact that the expertise necessary to properly and appropriately configure technology is usually not found in the same person. As one who has worked in both the world of educators and the world of information technology professionals, I can confirm that we do not want educators to be responsible for managing IT infrastructure and we do not want IT professionals making decisions about what happens in classrooms. A recurring theme in this book has been the collaborative work that results in efficacious IT management. In design/ construction this collaboration is most important.

School leaders have the authority to mediate decisions about whose recommendations are given priority at any moment. The attentive school leader will be able to ascertain where in the iterative planning cycle any design/ construction activity is and will resolve disputes accordingly. If teachers are complaining about how difficult a system is to use, then the school leader will determine if the proper use has been explained to the teachers and will determine if the complaining teachers are using the technology as it has been designed. If teachers are not using the system as it has been designed, then the school leader will direct teachers to follow instructions. If they are using the system as designed, but it is still inefficient or ineffective, then the school leader will direct the IT professionals to change the configuration of the system to more closely satisfy the teachers. When there is uncertainty about which configuration to direct, school leaders should accommodate teachers and students whenever it is reasonable, as the experiences of students are most critical to the purpose of the school.

Understanding Interventions

School and technology leaders who model their management after educational design research will engage in a process by which they make sense of the interventions that were implemented and the evidence they gathered. This process is intended to accomplish two goals. First, the IT managers seek to evaluate the degree to which the interventions contributed to the school achieving its strategic and logistic goals. Second, IT managers assess their interventions, the evidence they gathered, and the nature of their designs and products; through this inquiry, they articulate generalizations that can be applied to other planning problems. Based on the view of educational design and progressive discourse that has been presented in this chapter, it is more accurate to suggest IT managers evaluate the degree to which strategic and logistic goals are improved than to suggest IT managers evaluate the achievement of goals. Many school IT managers are motivated to analyze/ explore, then design/ construct interventions, to resolve a situation that is perceived to be a problem, so they will continue design/ construction iterations until the interventions are deemed satisfactory, and the problem solved. Even those interventions that are quickly deemed to have solved the problem should be the focus of evaluation/ assessment so the factors that led to the improvements can be articulated and used to inform other decisions and shared with other IT managers.

Compared to those who rely simply on data measured on a single instrument, IT planners who engage in educational design research use more sophisticated evidence to frame their work and this allows them to support more sophisticated generalizations. They can explain their rationale for the initial design decisions that were made as well as the design decisions made during each iteration; they can explain their conclusions and evaluate their evidence. They also tend to have deeper understanding of how the interventions were instantiated in the local community than other planners, so they can clarify the factors that were relevant for local circumstances and they are more prepared to evaluate the appropriateness of the conceptual artifacts, the cost of improvements, as well as to identify unintended consequences of the interventions. All of this contributes to decisions to maintain or change priorities for continued efforts to improve aspects of technology-rich teaching and learning.

Because their design decisions are grounded in theory and the data they collect are interpreted in light of that theory, IT managers use the theory as a framework to understand what effect their interventions and why those effects occurred. If predictions were not observed, then the situation can be more closely interpreted to either identify problems with the prediction, the evidence collected, or the design and construction of the intervention. It is also possible to identify unforeseen factors that affected a particular intervention, but this can only be done when theory is used to interpret the observations.

Generalizations that appear to be supported by observations can also be reported to the greater community, typically in presentations at conferences or in articles published in periodicals. This reporting of findings increases one’s professional knowledge of important practices and it also exposes the work to criticisms and reviews that improve the capacity of the IT manager to continue and that help all participants refine and clarify their knowledge.

The degree to which IT managers’ evaluation of interventions in the local community are valid and reliable and the degree to which their generalizations are accepted by the greater professional community is determined by the quality of the evidence they present. Evidence is based in fact. In the vernacular, fact typically means information that is true and accurate. Implicit, also, is the assumption that the fact is objectively defined so every observer will agree on the both reality of the fact and the meaning of the fact. For researchers, facts are grounded in assumptions and established through observation, and observation can refute an idea that was long-thought to be a true fact. For IT managers using educational design research to frame decisions, they seek to recognize assumptions and make decisions based on multiple observations.

Consider the example of a school in which school leaders become aware of evidence that hybrid learning is positively associated with students’ course grades (for example Scida & Saury, 2006). They may direct IT managers to install and configure a learning management system (LMS) so teachers can supplement their face-to-face instruction with online activities. Recognizing there is ambiguous evidence of the effectiveness of hybrid and elearning tools and platforms on learning (Desplaces, Blair, & Salvaggio, 2015), the IT managers who deployed the LMS may be interested in answering the question, “Did use of the LMS affect students’ learning?” Data-driven IT managers might simply compare the grades of students in sections that used the LMS to grades of students in sections that did not use the LMS. Those planners are assuming grades in courses really do reflect changes in what a student knows and can do (rather than reflecting teachers’ biases for example).

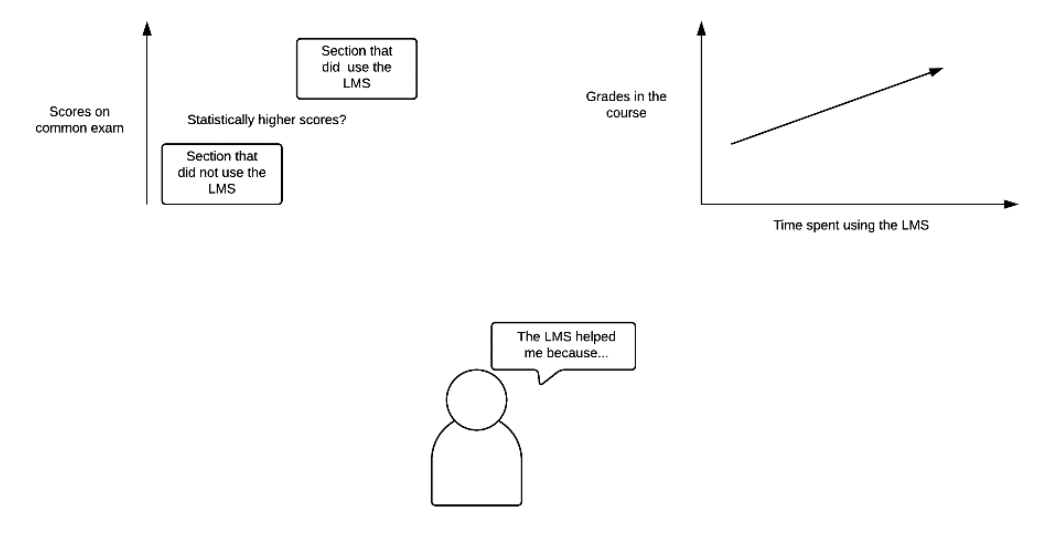

The first step in answering the question would be to ascertain if there was a difference in the grades between the students who used the LMS and those who do not. In adopting a researchlike stance towards the data, the IT managers would look for statistically significant differences between the grades of students in sections that used the LMS and those that did not. They may choose a specific course to study to minimize the number of variables that affect their observations. The efficacious IT manager would recognize these differences could be accounted for by many variables in addition to the use of the LMS and effects of the LMS might not appear in this initial comparison. Completely understanding the effects of the LMS of students’ learning of Algebra 1 (for example) necessitates further evidence and data; the most reliable and valid evidence includes data from at least three data sources. When studying the LMS, IT managers might answer three questions about the LMS and their students (see Figure 7.3.2).

One relevant measurement might be to compare the performance of different cohorts of students’ performance on a common test, such as a final exam given to all Algebra 1 students. Finding statistically significant differences between the scores of students who enrolled in a section in which the LMS was used compared those who enrolled in a section that did not use the LMS might indicate an effect of the LMS rather than an unrecognized effect. To minimize bias in such data collection, steps should be taken to ensure all of the exams were accurately scored and the statistical tests should be performed by those who do not know which group used the LMS (the treatment) and which did not (the control). This is an example of a quasi-experimental design, as the students in this case are unlikely to have been randomly assigned to the sections.

Figure \(\PageIndex{2}\): Multiple sources of data

A second observation might be to ascertain if greater use of the LMS is associated with higher scores within sections that used the LMS. The IT managers would have the ability to analyze access logs kept on the LMS that records when individual users log on to the system, and these patterns could be compared to individual students’ grades to determine if there is a correlation between use of the LMS and grades. While a positive correlation between access and grades does not necessarily indicate causation, such positive evidence can corroborate other observations.

A third source of evidence to understand the effects of the LMS on student grades might be to interview students to ascertain their experience using the LMS; the qualitative data collected in this way will help explain differences observed (or not observed) in other data. Together, these three sources of evidence given greater insight into the effects of the LMS on students’ learning than simply comparing grades.

Rationale for the Effort

Compared to other planning methods and other methods of gathering data and evidence, educational design research may be perceived as necessitating greater time and other resources. There are several advantages of this method, however, that justify its use.

First, IT managers adopt researchers’ objectivity and consistency and this reduces the conflict that can arise from the disparate views of the various stakeholders who are interpreting actions and outcomes from different perspectives. That objectivity and consistency also helps conserve the conceptual artifacts that IT planners seek to improve.

Second, students, teachers, and school administrators live and work in a dynamic and evolving environment in which outcomes have multiple causes and an action may have multiple effects. By collecting evidence from multiple sources, IT managers are more likely to understand the interventions as they were experienced by the community. Also, interventions that are developed through iterative processes are more likely to reflect theory. Theory tends to change more slowly than the methods that gain popularity only to be replaced when the next fad gains popularity. Theory-based evidence tends provide a more stable and sustained foundation for interventions that improve how conceptual artifacts are instantiated.

Third, education and technology are domains in which individuals can have seemingly sophisticated experiences, but these methods tend to minimize the threats posed by novices believing they are experts. Many educators have purchased a wireless router, to set up a home network. This can lead them to assume they have expertise in enterprise networking. Technologists are also prone to believe that the years they spent in school give them expert knowledge of teaching and learning. The clear language and diverse perspectives introduced to IT management adopting research methods preserves the complexity of each field while facilitating common understanding.

Fourth, by evaluating and reflecting on the design process as well as the quality of the interventions, IT managers make sense of the interventions they created and can account for their observations. Those conclusions improve their own ability to design similar interventions, contribute to growing institutional knowledge of how the interventions are instantiated in the community, and can support generalizations that can be used by other researchers and by other managers.