7: Does IT Matter?

- Page ID

- 4314

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\dsum}{\displaystyle\sum\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dint}{\displaystyle\int\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\dlim}{\displaystyle\lim\limits} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Learning Objectives

Upon successful completion of this chapter, you will be able to:

- define the productivity paradox and explain the current thinking on this topic;

- evaluate Carr’s argument in “Does IT Matter?”;

- describe the components of competitive advantage; and

- describe information systems that can provide businesses with competitive advantage.

Introduction

For over fifty years, computing technology has been a part of business. Organizations have spent trillions of dollars on information technologies. But has all this investment in IT made a difference? Have there been increases in productivity? Are companies that invest in IT more competitive? This chapter looks at the value IT can bring to an organization and attempts to answer these questions. Two important works in the past two decades have attempted to address this issue.

The Productivity Paradox

In 1991, Erik Brynjolfsson wrote an article, published in the Communications of the ACM, entitled “The Productivity Paradox of Information Technology: Review and Assessment.” After reviewing studies about the impact of IT investment on productivity, Brynjolfsson concluded that the addition of information technology to business had not improved productivity at all. He called this the “productivity paradox.” While he did not draw any specific conclusions from his work, [1] he did provide the following analysis.

Although it is too early to conclude that IT’s productivity contribution has been subpar, a paradox remains in our inability to unequivocally document any contribution after so much effort. The various explanations that have been proposed can be grouped into four categories:

- Mismeasurement of outputs and inputs

- Lags due to learning and adjustment

- Redistribution and dissipation of profits

- Mismanagement of information and technology

In 1998, Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt published a follow-up paper entitled “Beyond the Productivity Paradox [2] In this paper, the authors utilized new data that had been collected and found that IT did, indeed, provide a positive result for businesses. Further, they found that sometimes the true advantages in using technology were not directly relatable to higher productivity, but to “softer” measures, such as the impact on organizational structure. They also found that the impact of information technology can vary widely between companies.

IT Doesn’t Matter

Just as a consensus was forming about the value of IT, the Internet stock market bubble burst. Two years later in 2003, Harvard professor Nicholas Carr wrote his article “IT Doesn’t Matter” in the Harvard Business Review. In this article Carr asserted that as information technology had become ubiquitous, it has also become less of a differentiator, much like a commodity. Products that have the same features and are virtually indistinguishable are considered to be commodities. Price and availability typically become the only discriminators when selecting a source for a commodity. In Carr’s view all information technology was the same, delivering the same value regardless of price or supplier. Carr suggested that since IT is essentially a commodity, it should be managed like one. Just select the one with the lowest cost this is most easily accessible. He went on to say IT management should see themselves as a utility within the company and work to keep costs down. For Carr IT’s goal is to provide the best service with minimal downtime. Carr saw no competitive advantage to be gained through information technology.

As you can imagine, this article caused quite an uproar, especially from IT companies. Many articles were written in defense of IT while others supported Carr. In 2004 Carr released a book based on the article entitled Does IT Matter? A year later he was interviewed by CNET on the topic “IT still doesn’t matter.” Click here to watch the video of Carr being interviewed about his book on CNET.

Probably the best thing to come out of the article and subsequent book were discussions on the place of IT in a business strategy, and exactly what role IT could play in competitive advantage. That is the question to be addressed in this chapter.

Competitive Advantage

What does it mean when a company has a competitive advantage? What are the factors that play into it? Michael Porter in his book Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. writes that a company is said to have a competitive advantage over its rivals when it is able to sustain profits that exceed the average for the industry. According to Porter, there are two primary methods for obtaining competitive advantage: cost advantage and differentiation advantage. [3] So the question for I.T. becomes: How can information technology be a factor in one or both of these methods?

The following sections address this question by using two of Porter’s analysis tools: the value chain and the five forces model. Porter’s analysis in his 2001 article “Strategy and the Internet,” which examines the impact of the Internet on business strategy and competitive advantage, will be used to shed further light on the role of information technology in gaining competitive advantage.[4]

The Value Chain

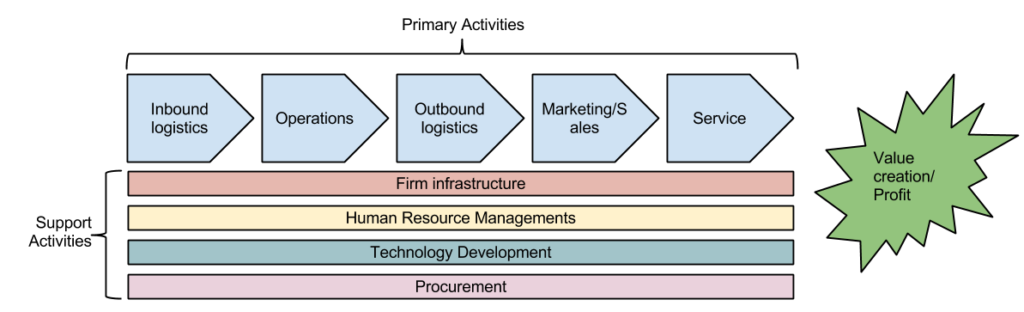

In his book Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Performance Porter describes exactly how a company can create value and therefore profit. Value is built through the value chain: a series of activities undertaken by the company to produce a product or service. Each step in the value chain contributes to the overall value of a product or service. While the value chain may not be a perfect model for every type of company, it does provide a way to analyze just how a company is producing value. The value chain is made up of two sets of activities: primary activities and support activities. An explanation of these activities and a discussion of how information technology can play a role in creating value by contributing to cost advantage or differentiation advantage appears next.

Primary activities are the functions that directly impact the creation of a product or service. The goal of a primary activity is to add value that is greater than the cost of that activity. The primary activities are:

- Inbound logistics. These are the processes that bring in raw materials and other needed inputs. Information technology can be used to make these processes more efficient, such as with supply-chain management systems which allow the suppliers to manage their own inventory.

- Operations. Any part of a business that converts the raw materials into a final product or service is a part of operations. From manufacturing to business process management (covered in Chapter 8), information technology can be used to provide more efficient processes and increase innovation through flows of information.

- Outbound logistics. These are the functions required to get the product out to the customer. As with inbound logistics, IT can be used here to improve processes, such as allowing for real-time inventory checks. IT can also be a delivery mechanism itself.

- Sales/Marketing. The functions that will entice buyers to purchase the products are part of sales and marketing. Information technology is used in almost all aspects of this activity. From online advertising to online surveys, IT can be used to innovate product design and reach customers as never before. The company website can be a sales channel itself.

- Service. Service activity involves the functions a business performs after the product has been purchased to maintain and enhance the product’s value. Service can be enhanced via technology as well, including support services through websites and knowledge bases.

The support activities are the functions in an organization that support all of the primary activities. Support activities can be considered indirect costs to the organization. The support activities are:

- Firm infrastructure. An organization’s infrastructure includes finance, accounting, ERP systems (covered in Chapter 9) and quality control. All of these depend on information technology and represent functions where I.T. can have a positive impact.

- Human Resource Management Human Resource Management (HRM) consists of recruiting, hiring, and other services needed to attract and retain employees. Using the Internet, HR departments can increase their reach when looking for candidates. I.T. also allows employees to use technology for a more flexible work environment.

- Technology development. Technology development provides innovation that supports primary activities. These advances are integrated across the firm to add value in a variety of departments. Information technology is the primary generator of value in this support activity.

- Procurement. Procurement focuses on the acquisition of raw materials used in the creation of products. Business-to-business e-commerce can be used to improve the acquisition of materials.

This analysis of the value chain provides some insight into how information technology can lead to competitive advantage. Another important concept from Porter is the “Five Forces Model.”

Porter’s Five Forces

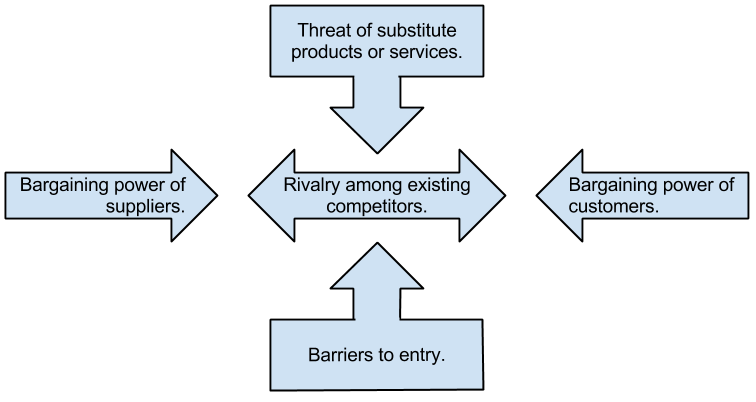

Porter developed the Five Forces model as a framework for industry analysis. This model can be used to help understand the degree of competition in an industry and analyze its strengths and weaknesses. The model consists of five elements, each of which plays a role in determining the average profitability of an industry. In 2001 Porter wrote an article entitled ”Strategy and the Internet,” in which he takes this model and looks at how the Internet impacts the profitability of an industry. Below is a quick summary of each of the Five Forces and the impact of the Internet.

- Threat of substitute products or services. The first force challenges the user to consider the likelihood of another produce or service replacing the product or service you offer. The more types of products or services there are that can meet a particular need, the less profitability there will be in an industry. In the communications industry, the smartphone has largely replaced the pager. In some construction projects, metal studs have replaced wooden studs for framing. The Internet has made people more aware of substitute products, driving down industry profits in those industries in which substitution occurs. Please notice that substitution refers to a product being replaced by a similar product for the purpose of accomplishing the same task. It does not mean dissimilar products or services such as flying to a destination rather than traveling by rail.

- Bargaining power of suppliers. A supplier’s bargaining power is strong when there are few suppliers from which your company can obtain a needed product or service. Conversely, when they are many suppliers their bargaining power is lower since your company would have many sources from which to source a product. When your company has several suppliers to choose from, you can negotiate a lower price. When a sole supplier exists, then your company is at the mercy of the supplier. For example, if only one company makes the controller chip for a car engine, that company can control the price, at least to some extent. The Internet has given companies access to more suppliers, driving down prices.

- Bargaining power of customers. A customer’s bargaining power is strong when your company along with your competitors is attempting to provide the same product to this customer. In this instance the customer has many sources from which to source a product so they can approach your company and seek a price reduction. If there are few suppliers in your industry, then the customer’s bargaining power is considered low.

- Barriers to entry. The easier it is to enter an industry, the more challenging it will be to make a profit in that industry. Imagine you are considering starting a lawn mowing business. The entry barrier is very low since all you need is a law mower. No special skills or licenses are required. However, this means your neighbor next door may decide to start mowing lawns also, resulting in increased competition. In contrast a highly technical industry such as manufacturing of medical devices has numerous barriers to entry. You would need to find numerous suppliers for various components, hire a variety of highly skilled engineers, and work closely with the Food and Drug Administration to secure approval for the sale of your products. In this example the barriers to entry are very high so you should expect few competitors.

- Rivalry among existing competitors: Rivalry among existing competitors helps you evaluate your entry into the market. When rivalry is fierce, each competitor is attempting to gain additional market share from the others. This can result in aggressive pricing, increasing customer support, or other factors which might lure a customer away from a competitor. Markets in which rivalry is low may be easier to enter and become profitable sooner because all of the competitors are accepting of each other’s presence.

Porter’s five forces are used to analyze an industry to determine the average profitability of a company within that industry. Adding in Porter’s analysis of the Internet to his Five Forces results in the realization that technology has lowered overall profitability. [5]

Using Information Systems for Competitive Advantage

Having learned about Porter’s Five Forces and their impact on a firm’s ability to generate a competitive advantage, it is time to look at some examples of competitive advantage. A strategic information system is designed specifically to implement an organizational strategy meant to provide a competitive advantage. These types of information systems began popping up in the 1980s, as noted in a paper by Charles Wiseman entitled “Creating Competitive Weapons From Information Systems.”[6]

A strategic information system attempts to do one or more of the following:

- Deliver a product or a service at a lower cost;

- Deliver a product or service that is differentiated;

- Help an organization focus on a specific market segment;

- Enable innovation.

Here are some examples of information systems that fall into this category.

Business Process Management Systems

In their book, IT Doesn’t Matter – Business Processes Do, Howard Smith and Peter Fingar argue that it is the integration of information systems with business processes that leads to competitive advantage. The authors state that Carr’s article is dangerous because it gave CEOs and IT managers approval to start cutting their technology budgets, putting their companies in peril. True competitive advantage can be found with information systems that support business processes. Chapter 8 focuses on the use of business processes for competitive advantage.

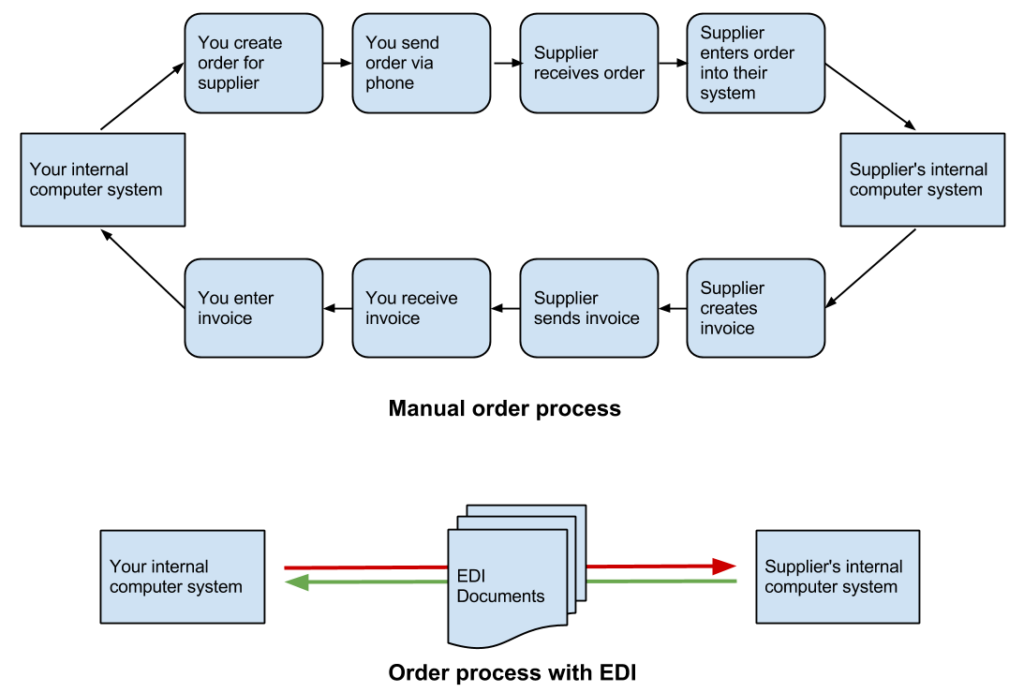

Electronic Data Interchange

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) provides a competitive advantage through integrating the supply chain electronically. EDI can be thought of as the computer-to-computer exchange of business documents in a standard electronic format between business partners. By integrating suppliers and distributors via EDI, a company can vastly reduce the resources required to manage the relevant information. Instead of manually ordering supplies, the company can simply place an order via the computer and the products are ordered.

Collaborative Systems

As organizations began to implement networking technologies, information systems emerged that allowed employees to begin collaborating in different ways. These systems allowed users to brainstorm ideas together without the necessity of physical, face-to-face meetings. Tools such as video conferencing with Skype or WebEx, collaboration and document sharing with Microsoft SharePoint, and project management with SAP’s Project System make collaboration possible in a variety of endeavors.

Broadly speaking, any software that allows multiple users to interact on a document or topic could be considered collaborative. Electronic mail, a shared Word document, and social networks fall into this broad definition. However, many software tools have been created that are designed specifically for collaborative purposes. These tools offer a broad spectrum of collaborative functions. Here is just a short list of some collaborative tools available for businesses today:

- Google Drive. Google Drive offers a suite of office applications (such as a word processor, spreadsheet, drawing, presentation) that can be shared between individuals. Multiple users can edit the documents at the same time and the threaded comments option is available.

- Microsoft SharePoint. SharePoint integrates with Microsoft Office and allows for collaboration using tools most office workers are familiar with. SharePoint was covered in greater detail in chapter 5.

- Cisco WebEx. WebEx combines video and audio communications and allows participants to interact with each other’s computer desktops. WebEx also provides a shared whiteboard and the capability for text-based chat to be going on during the sessions, along with many other features. Mobile editions of WebEx allow for full participation using smartphones and tablets.

- GitHub. Programmers/developers use GitHub for web-based team development of computer software.

Decision Support Systems

A decision support system (DSS) helps an organization make a specific decision or set of decisions. DSSs can exist at different levels of decision-making within the organization, from the CEO to first level managers. These systems are designed to take inputs regarding a known (or partially-known) decision making process and provide the information necessary to make a decision. DSSs generally assist a management level person in the decision-making process, though some can be designed to automate decision-making.

An organization has a wide variety of decisions to make, ranging from highly structured decisions to unstructured decisions. A structured decision is usually one that is made quite often, and one in which the decision is based directly on the inputs. With structured decisions, once you know the necessary information you also know the decision that needs to be made. For example, inventory reorder levels can be structured decisions. Once your inventory of widgets gets below a specific threshold, automatically reorder ten more. Structured decisions are good candidates for automation, but decision-support systems are generally not built for them.

An unstructured decision involves a lot of unknowns. Many times unstructured decisions are made for the first time. An information system can support these types of decisions by providing the decision makers with information gathering tools and collaborative capabilities. An example of an unstructured decision might be dealing with a labor issue or setting policy for the implementation of a new technology.

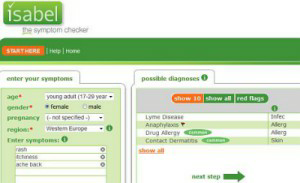

Decision support systems work best when the decision makers are having to make semi-structured decisions. A semi-structured decision is one in which most of the factors needed for making the decision are known but human experience and other outside factors may still impact the decision. A good example of an semi-structured decision would be diagnosing a medical condition (see sidebar).

As with collaborative systems, DSSs can come in many different formats. A nicely designed spreadsheet that allows for input of specific variables and then calculates required outputs could be considered a DSS. Another DSS might be one that assists in determining which products a company should develop. Input into the system could include market research on the product, competitor information, and product development costs. The system would then analyze these inputs based on the specific rules and concepts programmed into it. The system would report its results with recommendations and/or key indicators to be used in making a decision. A DSS can be looked at as a tool for competitive advantage because it can give an organization a mechanism to make wise decisions about products and innovations.

Sidebar: Isabel – A Health Care DSS

A discussed in the text, DSSs are best applied to semi-structured decisions, in which most of the needed inputs are known but human experience and environmental factors also play a role. A good example for today is Isabel, a health care DSS. The creators of Isabel explain how it works:

Isabel uses the information routinely captured during your workup, whether free text or structured data, and instantaneously provides a diagnosis checklist for review. The checklist contains a list of possible diagnoses with critical “Don’t Miss Diagnoses” flagged. When integrated into your Electronic Medical Records (EMR) system, Isabel can provide “one click” seamless diagnosis support with no additional data entry. [7]

Investing in IT for Competitive Advantage

In 2008, Brynjolfsson and McAfee published a study in the Harvard Business Review on the role of IT in competitive advantage, entitled “Investing in the IT That Makes a Competitive Difference.” Their study confirmed that IT can play a role in competitive advantage if deployed wisely. In their study, they drew three conclusions[8]:

- First, the data show that IT has sharpened differences among companies instead of reducing them. This reflects the fact that while companies have always varied widely in their ability to select, adopt, and exploit innovations, technology has accelerated and amplified these differences.

- Second, good management matters. Highly qualified vendors, consultants, and IT departments might be necessary for the successful implementation of enterprise technologies themselves, but the real value comes from the process innovations that can now be delivered on those platforms. Fostering the right innovations and propagating them widely are both executive responsibilities – ones that can’t be delegated.

- Finally, the competitive shakeup brought on by IT is not nearly complete, even in the IT-intensive US economy. You can expect to see these altered competitive dynamics in other countries, as well, as their IT investments grow.

Information systems can be used for competitive advantage, but they must be used strategically. Organizations must understand how they want to differentiate themselves and then use all the elements of information systems (hardware, software, data, people, and process) to accomplish that differentiation.

Summary

Information systems are integrated into all components of business today, but can they bring competitive advantage? Over the years, there have been many answers to this question. Early research could not draw any connections between IT and profitability, but later studies have shown that the impact can be positive. IT is not a panacea. Just purchasing and installing the latest technology will not by itself make a company more successful. Instead, the combination of the right technologies and good management will give a company the best chance for a positive result.

Study Questions

- What is the productivity paradox?

- Summarize Carr’s argument in “Does IT Matter.”

- How is the 2008 study by Brynjolfsson and McAfee different from previous studies? How is it the same?

- What does it mean for a business to have a competitive advantage?

- What are the primary activities and support activities of the value chain?

- What has been the overall impact of the Internet on industry profitability? Who has been the true winner?

- How does EDI work?

- Give an example of a semi-structured decision and explain what inputs would be necessary to provide assistance in making the decision.

- What does a collaborative information system do?

- How can IT play a role in competitive advantage, according to the 2008 article by Brynjolfsson and McAfee?

Exercises

- Analyze Carr’s position in regards to PC vs. Mac, Open Office vs. Microsoft Office, and Microsoft Powerpoint vs. Tableau.

- Do some independent research on Nicholas Carr (the author of “IT Doesn’t Matter”) and explain his current position on the ability of IT to provide competitive advantage.

- Review the WebEx website. What features of WebEx would contribute to good collaboration? Compare WebEx with other collaboration tools such as Skype or Google Hangouts?

Lab

- Think of a semi-structured decision that you make in your daily life and build your own DSS using a spreadsheet that would help you make that decision.

- Brynjolfsson, E. (1994). The Productivity Paradox of Information Technology: Review and Assessment. Center for Coordination Science MIT Sloan School of Management: Cambridge, Massachusetts.↵

- Brynjolfsson, E. and Hitt, L. (1998). Beyond the Productivity Paradox. Communications of the ACM, 41, 49–55. ↵

- Porter, M. (1985). Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New York: The Free Press. ↵

- Porter, M. (2001, March). Strategy and the Internet. Harvard Business Review, 79 ,3. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/2165.html ↵

- Porter, M. (2001, March). Strategy and the Internet. Harvard Business Review, 79, 3. Retrieved from http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/2165.html↵

- Wiseman, C. and MacMillan, I. C. (1984). Creating Competitive Weapons From Information Systems. Journal Of Business Strategy, 5(2)., 42.↵

- Isabel. (n.d.). Broaden Your Differential Diagnosis. Retrieved from http://www.isabelhealthcare.com/home/ourmission. ↵

- McAfee, A. and Brynjolfsson, E. (2008, July-August). Investing in the IT That Makes a Competitive Difference. Harvard Business Review.↵