1.3: The Role of Information Systems

- Page ID

- 9747

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Now that we have explored the different components of information systems (IS), we need to turn our attention to IS's role in an organization. From our definitions above, we see that these components collect, store, organize, and distribute data throughout the organization, which is the first half of the definition. We can now ask what do these components actually do for an organization to address the second part of the definition of an IS “to support decision making, coordination, control, analysis, and visualization in an organization” Earlier, we discussed how IS collects raw data to organize them to create new information to aid in the running of a business. To help management to make informed critical decisions, IS has to take the information further by transforming it into organizational knowledge. In fact, we could say that one of the roles of IS is to take data and turn it into information and then transform that into organizational knowledge. As technology has developed and the business world becomes more data-driven, so has IS's role, from a tool to run an organization efficiently to a strategic tool for competitive advantages. To get a full appreciation of IS's role, we will review how IS has changed over the years to create new opportunities for businesses and address evolving human needs.

The Early Years (1930s-1950s)

We may say that computer history came to public view in the 1930s when George Stibitz developed the “Model K” Adder on his kitchen table using telephone company relays and proved the viability of the concept of ‘Boolean logic,’ a fundamental concept in the design of computers. From 1939 on, we saw the evolution of special-purpose equipment to general-purpose computers by companies that are now iconic in the computing industry; Hewlett-Packard with their first product HP200A Audio Oscillator that Disney’s Fantasia used. The 1940s gave us the first computer program running a computer through the work of John von Newmann, Frederic Williams, Tom Kilburn, and Geoff Toothill. The 1950s gave us the first commercial computer, the UNIVAC 1, made by Remington Rand and delivered to the US Census Bureau; it weighed 29,000 pounds and cost more than $1,000,000 each. (Computer History Museum, n.d.)

Software evolved along with the hardware evolution. Grace Hopper completed A-0, the program that allowed programmers to enter instructions to hardware with English-like words on the UNIVAC 1. With the arrival of general and commercial computers, we entered what is now referred to as the mainframe era. (Computer History Museum, n.d.)

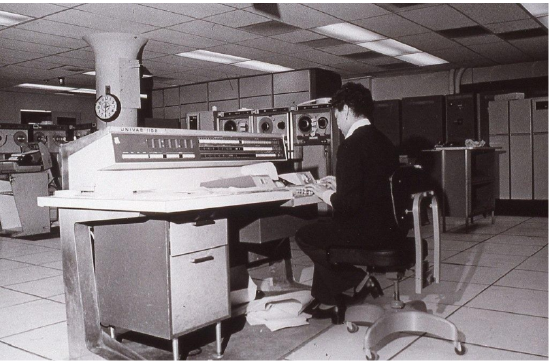

The Mainframe Era

From the late 1950s through the 1960s, computers were seen to more efficiently do calculations. These first business computers were room-sized monsters, with several refrigerator-sized machines linked together. These devices' primary work was to organize and store large volumes of information that were tedious to manage by hand. More companies were founded to expand the computer hardware and software industry, such as Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC), RCA, and IBM. Only large businesses, universities, and government agencies could afford them, and they took a crew of specialized personnel and specialized facilities to install them.

IBM introduced System/360 with five models. It was hailed as a major milestone in computing history for it was targeted at business besides the existing scientific customers, and equally important, all models could run the same software (Computer History, n.d.). These models could serve up to hundreds of users at a time through the technique called time-sharing. Typical functions included scientific calculations and accounting under the broader umbrella of “data processing.”

In the late 1960s, the Manufacturing Resources Planning (MRP) systems were introduced. This software, running on a mainframe computer, gave companies the ability to manage the manufacturing process, making it more efficient. From tracking inventory to creating bills of materials to scheduling production, the MRP systems (and later the MRP II systems) gave more businesses a reason to integrate computing into their processes. IBM became the dominant mainframe company. Nicknamed “Big Blue,” the company became synonymous with business computing. Continued software improvement and the availability of cheaper hardware eventually brought mainframe computers (and their little sibling, the minicomputer) into most large businesses.

The PC Revolution

The 1970s ushered in the growth era in both making the computers smaller- microcomputers, and faster big machines- supercomputers. In 1975, the first microcomputer was announced on the cover of Popular Mechanics: the Altair 8800, invented by Ed Roberts, who coined the term “personal computer.” The Altair was sold for $297-$395, and came with 256 bytes of memory, and licensed Bill Gates and Paul Allen’s BASIC programming language. Its immediate popularity sparked entrepreneurs' imagination everywhere, and there were quickly dozens of companies making these “personal computers.” Though at first just a niche product for computer hobbyists, improvements in usability and practical software availability led to growing sales. The most prominent of these early personal computer makers was a little company known as Apple Computer, headed by Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, with the hugely successful “Apple II .” (Computer History Museum, n.d.)

Hardware companies such as Intel and Motorola continued to introduce faster and faster microprocessors (i.e., computer chips). Not wanting to be left out of the revolution, in 1981, IBM (teaming with a little company called Microsoft for their operating system software) released their own version of the personal computer, called the “PC.” Businesses, which had used IBM mainframes for years to run their businesses, finally had the permission they needed to bring personal computers into their companies, and the IBM PC took off. The IBM PC was named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” in 1982.

Because of the IBM PC’s open architecture, it was easy for other companies to copy or “clone” it. During the 1980s, many new computer companies sprang up, offering less expensive versions of the PC. This drove prices down and spurred innovation. Microsoft developed its Windows operating system and made the PC even easier to use. Common uses for the PC during this period included word processing, spreadsheets, and databases. These early PCs were not connected to any network; for the most part, they stood alone as islands of innovation within the larger organization. The price of PCs becomes more and more affordable with new companies such as Dell.

Today, we continue to see PCs' miniaturization into a new range of hardware devices such as laptops, Apple iPhone, Amazon Kindle, Google Nest, and the Apple Watch. Not only did the computers become smaller, but they also became faster and more powerful; the big computers, in turn, evolved into supercomputers, with IBM Inc. and Cray Inc. among the leading vendors.

Client-Server

By the mid-1980s, businesses began to see the need to connect their computers to collaborate and share resources. This networking architecture was referred to as “client-server” because users would log in to the local area network (LAN) from their PC (the “client”) by connecting to a powerful computer called a “server,” which would then grant them rights to different resources on the network (such as shared file areas and a printer). Software companies began developing applications that allowed multiple users to access the same data at the same time. This evolved into software applications for communicating, with the first prevalent use of electronic mail appearing at this time.

This networking and data sharing all stayed within the confines of each business, for the most part. While there was sharing of electronic data between companies, this was a very specialized function. Computers were now seen as tools to collaborate internally within an organization. In fact, these computers' networks were becoming so powerful that they were replacing many of the functions previously performed by the larger mainframe computers at a fraction of the cost.

During this era, the first Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems were developed and run on the client-server architecture. An ERP system is a software application with a centralized database that can be used to run a company’s entire business. With separate modules for accounting, finance, inventory, human resources, and many more, ERP systems, with Germany’s SAP leading the way, representing state of the art in information systems integration. We will discuss ERP systems as part of the chapter on Process (Chapter 9).

The Internet, World Wide Web, and Web 1.0

Networking communication along with software technologies evolve through all periods: the modem in the 1940s, clickable link in the 1950s, the email as the “killer app’ and now iconic “@” the mobile networks in the 1970s, and the early rise of online communities through companies such as AOL in the early 1980s. First invented in 1969 as part of a US-government funded project called ARPA, the Internet was confined to use by universities, government agencies, and researchers for many years. However, the complicated way of using the Internet made it unsuitable for mainstream use in business.

One exception to this was the ability to expand electronic mail outside the confines of a single organization. While the first email messages on the Internet were sent in the early 1970s, companies who wanted to expand their LAN-based email started hooking up to the Internet in the 1980s. Companies began connecting their internal networks to the Internet to communicate between their employees and employees at other companies. With these early Internet connections, the computer truly began to evolve from a computational device to a communications device.

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee from CERN laboratory developed an application (CERN, n.d.), a browser, to give a simpler and more intuitive graphical user interface to existing technologies such as clickable link, to make the ability to share and locate vast amounts of information easily available to the mass in addition to the researchers. This is what we called as the World Wide Web. 4 This invention became the launching point of the growth of the Internet as a way for businesses to share information about themselves and for consumers to find them easily.

As web browsers and Internet connections became the norm, companies worldwide rushed to grab domain names and create websites. Even individuals would create personal websites to post pictures to share with friends and family. For the first time, users could create content on their own and join the global economy.

In 1991, the National Science Foundation, which governed how the Internet was used, lifted restrictions on its commercial use. These policy changes ushered in new companies establishing new e-commerce industries such as eBay and Amazon.com. The fast expansion of the digital marketplace led to the dot-com boom through the late 1990s and then the dot-com bust in 2000. An important outcome of the Internet boom period was that thousands of miles of Internet connections were laid around the world during that time. The world became truly “wired” heading into the new millennium, ushering in the era of globalization, which we will discuss in Chapter 11.

The digital world also became a more dangerous place as more companies and users were connected globally. Once slowly propagated through the sharing of computer disks, computer viruses and worms could now grow with tremendous speed via the Internet and the proliferation of new hardware devices for personal or home use. Operating and application software had to evolve to defend against this threat, and a whole new industry of computer and Internet security arose as the threats kept increasing and became more sophisticated. We will study information security in Chapter 6.

Web 2.0 and e-Commerce

Perhaps, you noticed that in the Web 1.0 period, users and companies could create content but could not interact with each other directly on a website. Despite the Internet's bust, technologies continue to evolve due to increased needs from customers to personalize their experience and engage directly with businesses.

Websites become interactive; instead of just visiting a site to find out about a business and purchase its products, customers can now interact with companies directly, and most profoundly, customers can also interact with each other to share their experience without undue influence from companies or even buy things directly from each other. This new type of interactive website, where users did not have to know how to create a web page or do any programming to put information online, became known as web 2.0.

Web 2.0 is exemplified by blogging, social networking, bartering, purchasing, and post interactive comments on many websites. This new web-2.0 world, in which online interaction became expected, had a big impact on many businesses and even whole industries. Some industries, such as bookstores, found themselves relegated to niche status. Others, such as video rental chains and travel agencies, began going out of business as online technologies replaced them. This process of technology replacing an intermediary in a transaction is called disintermediation. One such successful company is Amazon which has disintermediated many intermediaries in many industries, and it is one of the leading e-commerce websites.

As the world became more connected, new questions arose. Should access to the Internet be considered a right? What is legal to copy or share on the internet? How can companies protect data (kept or given by the users) private? Are there laws that need to be updated or created to protect people’s data, including children’s data? Policymakers are still catching up with technology advances even though many laws have been updated or created. Ethical issues surrounding information systems will be covered in Chapter 12.

The Post PC and Web 2.0 World

After thirty years as the primary computing device used in most businesses, sales of the PC are now beginning to decline as tablets and smartphones are taking off. Just as the mainframe before it, the PC will continue to play a key role in business but will no longer be the primary way people interact or do business. The limited storage and processing power of these mobile devices is being offset by a move to “cloud” computing, which allows for storage, sharing, and backup of the information on a massive scale.

Users continue to push for faster and smaller computing devices. Historically, we saw that microcomputers displaced mainframes, laptops displaced (almost) desktops. We now see that smartphones and tablets are displacing laptops in many situations. Will hardware vendors hit the physical limitations due to the small size of devices? Is this the beginning of a new era of invention of new computing paradigms such as Quantum computing, a trendy topic that we will cover in more detail in Chapter 13?

Tons of content has been generated by the users in the web 2.0 world, and businesses have been monetizing this user-generated content without sharing any of their profits. How will the role of users change in this new world? Will the users want a share of this profit? Will the users finally have ownership of their own data? What new knowledge can be created from the massive user-generated and business-generated content?

Below is a chart showing the evolution of some of the advances in information systems to date.

|

Era |

Hardware |

Operating System |

Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Early years (1930s) |

Model K, HP’s test equipment, Calculator, UNIVAC 1 |

The first computer program was written to run and store on a computer. |

|

|

Mainframe (1970s) |

Terminals connected to a mainframe computer, IBM System 360 |

Time-sharing (TSO) on MVS |

Custom-written MRP software |

|

PC (mid-1980s) |

IBM PC or compatible. Sometimes connected to the mainframe computer via an expansion card. Intel microprocessor |

MS-DOS |

WordPerfect, Lotus 1-2-3 |

|

Client-Server (the late 80s to early 90s) |

IBM PC “clone” on a Novell Network. Apple’s Apple-1 |

Windows for Workgroups, MacOS |

Microsoft Word, Microsoft Excel, email |

|

World Wide Web (the mid-90s to early 2000s) |

IBM PC “clone” connected to the company intranet. |

Windows XP, macOS |

Microsoft Office, Internet Explorer |

|

Web 2.0 (mid-2000s to present) |

Laptop connected to company Wi-Fi. Smartphones |

Windows 7, Linux, macOS |

Microsoft Office, Firefox, social media platforms, blogging, search, texting |

|

Post-Web 2.0 (today and beyond) |

Apple iPad, robots, Fitbit, watch, Kindle, Nest, cars, drones |

iOS, Android, Windows 10 |

Mobile-friendly websites, more mobile apps eCommerce |

We seem to be at a tipping point of many technological advances that have come of age. The miniaturization of devices such as cameras, sensors, faster and smaller processors, software advances in fields such as artificial intelligence, combined with the availability of massive data, have begun to bring in new types of computing devices, small and big, that can do things that were unheard in the last four decades. A robot the size of a fly is already in limited use, a driverless car is in the ‘test-drive’ phase in a few cities, among other new advances to meet customers’ today needs and anticipate new ones for the future. “Where do we go from here?” is a question that you are now part of the conversation as you go through the rest of the chapters. We may not know exactly what the future will look like, but we can reasonably assume that information systems will touch almost every aspect of our personal, work-life, local and global social norms. Are you prepared to be an even more sophisticated user? Are you preparing yourself to be competitive in your chosen field? Are there new norms to be embraced?

References

Timeline of Computer History: Computer History Museum. (n.d.). Retrieved July 10, 2020, from https://www.computerhistory.org/timeline/computers/

CERN. (n.d.) The Birth of the Web. Retrieved from http://public.web.cern.ch/public/en/about/web-en.html